State Protection Gap Risk Management – Financial Foundations for Resilience

About this report

Published on: October 15, 2021

Large parts of society are ill-equipped to prevent, mitigate or recover from major threats and shocks. There is little to incentivise many organisations to prepare for low-probability events, to spend money on resilience or preparedness activities which may never be necessary or not required until some unspecified time in the future, or that government will have to bail out anyway.

Insurance has played a major role in the past in helping the nation to manage risk and this paper explores how the sector can help to close the existing protection gap.

Authors

Lord Toby Harris, Chair, National Preparedness Commission

Professor Michael Mainelli, Executive Chairman, Z/Yen Group

Background

John Locke wrote: ‘Government has no other end but the preservation of Property.’ Following the 10 April 1992 bombing which devastated the Baltic Exchange for shipping, insurers withdrew cover for acts of terrorism. In response, the UK Government rapidly formed a new government reinsurer called Pool Re. Pool Re was emulated by the US after 9/11.

Pool Re has been particularly well run over nearly three decades, remaining in significant surplus and supporting a broad property market while building business confidence. Further, it was set up with the aim of attracting other reinsurers into the market, at which it has also been successful. Pool Re is an example of the government spending virtually nothing, but achieving a lot of risk management through sensible use of financial instruments.

This reinsurance idea can be extended. For example, the government wants the UK to be free of cyber-crime. Cyber-crime insurance is a market where it is hard to get significant risks underwritten. Related cyber-terrorism, e.g. state sponsored terrorism, insurance does not exist. Cyber-crime exists and hurts financially, partly because it is difficult to insure. Cyber-crime could be deemed to be under control when people can buy normal insurance, just like home insurance against burglary or fire. We have long had export guarantee schemes that protect against foreign defaults. Similarly, there is the Financial Services Compensation Scheme that protects depositors if a bank fails to meet its financial obligations. Other suggestions include pension indemnity assurance or overseas students’ fee guarantees against a UK university default in order to bring business to the UK.

Equally, initiatives such a Flood Re seem related but are more about shifting an existing problem than managing down risks. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, there have been significant questions about how insurance might help reduce the impact of another panic. The question is wider: how could insurance reduce the impact of all significant risks on the national risk register?

What’s the problem?

Large parts of society are ill-equipped to prevent, mitigate or recover from major threats and shocks. There is little to incentivise many organisations to prepare for low-probability events, to spend money on resilience or preparedness activities which may never be necessary or not required until some unspecified time in the future, or that government will have to bail out anyway. Recovery from major shocks may far exceed the readily available resources of many organisations. It may be impossible to insure against such risks if the insurance markets are unavailable or too shallow.

Insurance has played a major role in the past in helping the nation to manage risk. Recall that: the development of fire insurance led to much better assessment and high standards leading to enormously reduced fire incidents; universal automotive coverage led to many fewer accidents and automotive thefts; workers’ compensation cover led to many fewer injuries; and non-compulsory home and contents insurance led to many fewer burglaries.

However, insurance plays an important role beyond just distributing money after losses. Insurance is a mechanism for encouraging innovation, establishing value for money, and spreading risk management best practice. A good example of such activity is the NHS Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts (CNST). Begun in 1990, this compulsory scheme charges insurance premia to trusts based on their assessed clinical risk. In turn, trusts attempt to reduce their premia by reducing clinical problems and improving their track record. The lessons they learn are shared via the CNST assessors and a virtuous circle of improvement is the result. While money is used to motivate improvement, the overall goal is risk reduction.

Who owns the problem?

It is not clear who is responsible for systemic resilience. At one level, it is a whole-of-society problem, so it is for government to ensure that these issues are addressed. Brendan Greeley paints politicians as insurers: ‘You could think of politicians as underwriters, … they must compare the probabilities of low-frequency events, weighing the risk of a downturn against a sovereign default, or of Chinese imperial ambition against more small wars in the Middle East, or of climate change against the cost of regulation.’ [1]

The absence of arrangements may pose an existential threat to some organisations. Interdependency means that protection for all may be necessary. The ability to withstand and recover from serious shocks gives organisations and the nation a better competitive advantage.

Since the pandemic, there have been discussions among insurers of a rather direct public-private reinsurer, Pandemic Re, for future pandemics. There have also been discussions about learning wider lessons from several successful schemes to create a public-private reinsurer under such discussion names as Recover Re, Totus Re, and Black Swan Re.

What’s the big idea?

More ‘broadly-based, public-private catastrophe risk management’ could make the nation more resilient. Such a scheme, for the sake of discussion a State Protection Gap Risk Management Entity (SPGRME), would start with the National Risk Register to specify the major risks it would cover. Critical national infrastructure (CNI) organisations might form a compulsory core. Commercial insurers and reinsurers might be encouraged by their regulators to participate. Other organisations might apply to join, especially those on the edge of being CNI such as the many firms that during the pandemic turned out to provide ‘front-line workers’ e.g. supermarkets. SPGRME would provide these organisations with business or operational interruption insurance. In the event of a major risk materialising, money would become available to SPGRME’s clients.

SPGRME could require those insured to carry out a specified level of resilience preparedness activity in order to provide coverage or in exchange for reduced premiums. SPGRME would act as the underwriter-of-last-resort to support pay-outs for recovery from catastrophic events. It is important to distinguish between insuring against all risks in the risk register, and more sensibly insuring against the common systemic impacts that could be caused by any number of black swan events e.g. not insuring against a Carrington event (a solar coronal mass ejection) but rather against the outage of telecommunications infrastructure.

Benefits

Higher levels of preparedness and resilience provide the ability for nations to recover better and more quickly in the aftermath of major shocks. SPGRME is more about the identification and solutions to problems in advance, and sharing best practice than about the use of financial tools after events. However, the financial discipline in running a proper insurer makes all the difference in helping organisations take preparation seriously and make appropriate cost-benefit decisions. The costs of building better protection and resilience are borne by organisations in a proportionate manner.

Risks and issues

There will be problems of structure and problems of delivery. On structure, there is much to learn from successes, such as Pool Re or CNST, and from less successful models, such as the US Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA), or from disaster relief zones, for example, that encourage risky behaviour in future. SPGRME, run well, is not a cost to the government, rather a mechanism to get society working together on major risks. Even in the event of a major catastrophe, SPGRME should be reducing the impact in advance, thus saving money and lives. SPGRME is there to change behaviour, not result in a compliance tick-box approach from its policy-holders. The composition of the core policy holders and the degree of compulsion will be important. SPGRME will also need to consider mechanisms for extending beyond the typical annual cycle of insurance.

Insurance is a ‘mechanism’ not a ‘solution’. The SPGRME should pick a small set of risks, e.g. health or cyber, inside a structured framework with a view to expanding based on learning. The mechanisms of insurance, risk assessment, information transfer and near-miss notifications are amongst the benefits sought. On delivery, it is important to maintain financial discipline. If cover is provided cheaply, then it does little. If cover is provided as a subsidy, then it can, in some cases, encourage adverse behaviour. A wider risk management approach realises that the benefits flow as much or more from information sharing and standards as from any financial transfers. Finance is there to give measurement and ‘teeth’ to information sharing and standards.

HM Treasury has already published ‘Government As Insurer Of Last Resort: Managing Contingent Liabilities In The Public Sector’ (March 2020). This report has a number of case studies providing useful examples of how individual risks are managed. Successful case studies include: UK Export Finance (p35), Department for International Development (p36), Infrastructure Projects Authority – UK Guarantees Scheme (p37), British Business Bank – Enterprise Finance Guarantee (p 38), NHS Resolution (p39), Pension Protection Fund (p40), and, of course, Pool Re (p41). There are several options for a structure or structures and it is too early to propose anything specific. However, the core point is that there is a need for a structure developed in partnership between UK Government and the private sector to cover these protection gaps.

Cass Business School explored the missing links between the state and the market, describing it ‘as the protection gap, some 70% of global losses from natural catastrophes are not insured, equating to $1.3 trillion over the past 10 years. In 2017 alone, uninsured losses for weather-related disasters were estimated to be around $180 billion. At the same time, other forms of large-scale risk, such as terrorism, cyberattacks and pandemics are also increasing, with little financial protection to address the aftermath.’ [2] The report’s international perspective ranged widely to include protection gap entities such as: the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF), a multi-sovereign risk pool set up to provide its member states with access to rapid capital for responding to the aftermath of natural disasters as diverse as tropical cyclone, earthquake, and excess rainfall; the California Earthquake Authority (CEA), a privately funded, publicly managed Public Gap Entity (PGE) set up to support the primary insurance market in providing earthquake insurance to Californian homeowners; and the Australian Reinsurance Pool Corporation (ARPC), a terrorism reinsurance pool set up to provide reinsurance to insurance companies offering terrorism cover on commercial businesses in Australia.

Who owns the solution?

As a whole-of-society issue, ultimately government has to ‘own’ moving towards a SPGRME. However, government should be doing so with full support from those charged with preparedness and emergencies, with support from CNI facilities, and support from the private sector.

Next steps

The purpose of this paper is to propose that industry takes forward the thinking in ‘Government as Insurer of Last Resort’ by providing a submission to HM Treasury outlining how a SPGRME framework would help. It would help enormously if HM Treasury were able to indicate in advance its willingness to work with the private sector in developing this thinking, and willingness to receive such a submission for consideration.

Appendix A – Government’s Role in Insurance

A quick riposte to government involvement in insurance is that it might raise a contingent liability on the government’s balance sheet. A contrary response is that many of these outcomes, cyber-crime or defunct pensions for example, will wind up on the government balance sheet if they occur, so insurance suggestions are good ways of using finance to make markets move outcomes in the right direction.

A good example of these risks not being contingent is the Covid-19 pandemic. ‘Pandemic influenza’ featured on many risk registers from before 2020, not least the World Economic Forum’s and the UK Government’s National Risk Register from 2008, as high risk and high likelihood. Despite these high ratings, levels of preparation were poor. When the risks materialised, they were certainly not contingent, merely risks that were materially unaddressed over the years. The government wound up being the insurer of last resort for direct costs, business interruption, and unemployment.

‘In practice, the government supplies contingent liquidity through a variety of policies and interventions, including the conduct of monetary policy, the provision of deposit insurance, the occasional bailout of commercial banks, investment banks, pension funds and other institutions like Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. Also, a whole range of social insurance programs (unemployment insurance and social security, etc.) and of implicit catastrophe insurance (earthquakes, nuclear accidents, etc.) play an important role in influencing the amount of aggregate liquidity in the economy.’ [3]

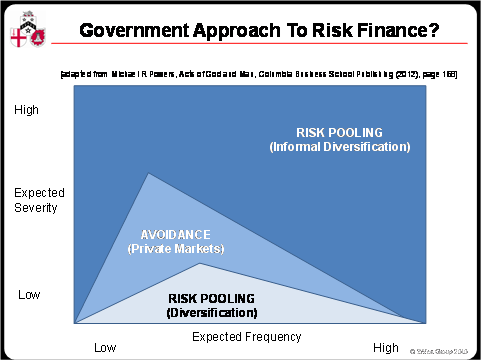

An interesting point arises when contrasting commercial and government approaches to insurance. A commercial approach by insurers works on risk selection. There is a whole bunch of risks in the outside world that can’t be insured or insured for reasonable cost, so risk control is the dominant approach. Once risk can be transferred, people hedge, typically via derivatives. If the risk can be pooled, then people use insurance.

‘Unlike an insurance company, a national government cannot actually avoid any particular category of risk. Therefore, all exposures in the top-most region (with high expected severities, whether associated with low or high expected frequencies) must be accepted, albeit reluctantly by the government. However, because of the political difficulty associated with setting aside sufficient financial reserves for these costliest of exposures, the government will tend to address them only as they occur, on a pay-as-you-go basis. In the bottom-most region, the government can take advantage of the likely presence of many similar and uncorrelated claims with low expected severities, so this region is much like the corresponding region for insurance companies. Here, the government sets aside formal reserves for various social insurance programs (e.g. pensions, health insurance and unemployment/disability benefits). Finally, in the middle region, the government typically tries its best to avoid these risks by encouraging firms and individuals to rely on their own private insurance products (but naturally, does not always succeed).’ [4]

Government’s special role means it helps to create liquidity throughout the country, and liquidity aids price discovery, which engenders more rational capital allocation.

Appendix B – National Preparedness Commission

The National Preparedness Commission was launched in 2020 to help ensure that the UK is better prepared for whatever the next crisis might be, and whatever form it might take. The Commission consists of 45 senior figures from public life, academia, business and civil society (list), all of whom are determined to ensure that the development of a more resilient society is informed by our collective understanding of the challenges of responding to, and preparing for, past and future crises. The Commission has already attracted support from a wide range of public and private-sector partners and has commissioned research from various academic institutions, recently publishing a well-received report from Cranfield University on ‘Resilience Reimagined’, based on interviews with 50 senior leaders from large companies and organisations. Further work aims to look at topics such as:

- Building cross-sectoral resilience across the public and private sectors;

- Harnessing the power of the market so that it pays to be resilient;

- Building societal and community resilience;

- Preparedness and place – what constitutes a resilient city or locality;

- The links between resilience, sustainability and the net-zero agenda.

Papers are being prepared on such topics as: translating ‘lessons identified’ into ‘lessons acted upon’ following major crises and events; and warnings and alerting systems. The Commission is also conducting a major review of the Civil Contingencies Act 2004 and the operation of Local Resilience Forums.

Appendix C – Z/Yen Group

Z/Yen Group is the City of London’s leading think-tank, founded in 1994 to promote societal advance through better finance and technology. The practice is built around a core of high-powered project managers, supported by experienced technical specialists so that clients get the expertise they need, rather than just the resources available. Z/Yen helps organisations make better choices: clients consider us a commercial think tank that spots, solves and acts to enhance reward, control risk, reduce volatility. Since the 1990s, Z/Yen has helped create a wide range of public and private risk management structures.

References:

[1] Greeley, B. The God Clause and the Reinsurance Industry, Bloomberg Businessweek, 1 September 2011. http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/the-god-clause-and-the-reinsurance-industry-09012011.html#p5

[2] Jarzabkowski, P., Cacciatori, E., Chalkias, K., Bednarek, R. Between State And Market: Protection Gap Entities And Catastrophic Risk, (June 2018). https://www.bayes.city.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/420257/PGE-Report-FINAL.pdf

[3] Holmström, B., and Tirole, J. Inside and Outside Liquidity, MIT Press (2011), p229.

[4] Powers, M R. Acts of God and Man, Columbia Business School Publishing (2012), pp168-169.