The Data-sharing Imperative: Lessons from the Pandemic

About this report

Published on: January 10, 2022

This paper has been produced following research into data-sharing lessons learned from the pandemic. The research sought to understand the current complex landscape and explore scenarios where data sharing would have helped other organisations provide a better response. A wide range of participants across water, fire, gas, power, Voluntary and Community Sectors, Local Resilience Forums, charities, Health & Social Care organisations took part in the research.

Authors

Dr Andrea Simmons CIPP/E, CIPM

Foreword

In any crisis or emergency, getting help and assistance to the most vulnerable is a priority. The Covid-19 pandemic has been no exception. However, the knowledge of who is vulnerable and the nature of their needs are usually dispersed. Some information will be known to local authorities and the emergency services, to the local NHS or GPs. Particular issues faced by their customers will be known to the banks or to the utilities that serve their homes. Voluntary and community groups may also be providing help in some cases; and there will be others whose potential problems are known only to family, friends and neighbours.

The challenge is how to make sure that this dispersed knowledge is brought together before times of crisis. Those in vulnerable circumstances may often be reluctant to come forward despite their very real needs or may not be able to do so because of what has happened. And it is crucial for the agencies that can help to know what those needs are and to understand the individuals concerned.

This report clearly shows that such data sharing is not only legal but does not require prior consent when sharing information that protects the individual and is in the wider public interest. Research has shown that most people welcome this proactive approach of ‘tell once’ to enable a wider network of support.

I hope that this report will make all the relevant agencies much more confident of the legal basis that allows them to ‘dare to share’ and encourage them to plan ahead so as to maximise the opportunity to respond rapidly to meet the needs of the most vulnerable before a crisis hits.

I am grateful to Thames Water for their thought leadership on this subject and their support for this report.

Lord Toby Harris

Chairman, National Preparedness Commission

What?

This paper, commissioned by the National Preparedness Commission, has been produced following research into data-sharing lessons learned from the pandemic.

How?

Understanding the current complex landscape and exploring scenarios where data sharing would have helped other organisations provide a better response.

Who?

Wide-ranging participants across water, fire, gas, power, Voluntary and Community Sectors, Local Resilience Forums, charities, Health & Social Care.

Why?

To benefit utility and service provide, as well as regulators and ultimately their customers.

Executive Summary

The Covid-19 pandemic led the UK to shut down in March 2020. This paper explains how better data sharing would have enabled better delivery of services to vulnerable customers and those most impacted by changing circumstances, and how the number of perceived data-protection challenges could be reduced. Greater trust is required between agencies, alongside embedded practices, processes and supporting technology, that will facilitate a philosophy of ‘dare to share’ so as to improve customer outcomes.

Through the lens of data sharing, the principal lessons from recent events, including flooding, other climate-related incidents and the Covid-19 pandemic are:

- Data sharing is complex but Proportionate effort is required, consistently querying whether data sharing is reasonable and/or necessary. What may be considered to be lawful may not be perceived to be reasonable. Staying outcome focused will lead to greater success – accurate data and service provision is the outcome (as opposed to a specific process). In particular, focus should be on needs not medical condition.

- Too often the legal framework is presented as preventing data sharing but, in fact, it permits data sharing to protect individuals and for the wider public Existing data-protection legislation provides an adequate roadmap to achieve effective, fair, secure, ethical and lawful data sharing. Wider knowledge of the legislative landscape is required in order to achieve a joined-up, regulatory approach.

- Whilst the powers to share across public-sector bodies largely already exist, the private sector requires increased data-sharing incentives.

- Data sharing needs to be both easy and systemic in normal times, not just an activity required in an Therefore, through legal mandate across all sectors¹, data sharing needs to be a foundational part of all resilience activities at local, regional and national levels.

- Increased trust and transparency are fundamental to normalising data sharing between participating bodies and between them and their customer base.

Knowing the inherent value of data sharing reduces the communication burden on the customer. This should be the watchword of all engagements, consciously identifying the purpose of any data sharing, and then achieving it as smoothly as possible.

Recommendations

The following recommendations have been grouped into themes:

Theme 1: Accountability and Transparency

Clear intent and purpose are required in order to prioritise data sharing. Focus should be on the opportunity rather than any perceived risk resulting from data sharing. The overall mindset needs to change from fear and risk aversion to opportunity management. Alignment of reputational and political risk must be balanced. Overall – dare to share.

Consider what a reasonable expectation is in the event of a pandemic or any other extreme, challenging, unforeseen emergency versus what is a routine expectation under normal pressures.

Ensure transparency by setting out with whom the data are being shared under normal circumstances, then also state what data might be shared in an emergency. This should already be covered in your Privacy Notice(s).

Theme 2: Consent

Ensure that customers or residents are clear that their health and safety and wellbeing are why their data may be shared. Consent is not required. Their understanding, willingness and co-operation are required. Rather than allowing fear of breaking the law to impede any ability to protect a vulnerable customer, always consider what the worst is that could happen, to ensure the actions are outcome focused. Focus on the threat rather than the harm.

Theme 3: Managing Vulnerability

The core purpose of the Priority Service Register (PSR) is to ensure that residents are ‘Safe, warm and independent’ in their homes. Consider placing everyone over 80 on the PSR equivalent; communicate this and then move on to the next identified set of vulnerable customers.

Ensure it is possible to maintain an individual’s right to remove themselves from any relevant register. Allow self-identification of vulnerability and develop and maintain practices to support this.

If the nomenclature of vulnerable customer is challenging, refer to ‘resilience events’ rather than vulnerabilities.

Enable a more agile and human-centred response, identifying people who are particularly vulnerable – across multiple areas of life including age, condition, available GP information, winter preparedness, etc – and allow agencies to better support those with trauma from an emergency, saving them from having to tell their story over and over again to different agencies. Correspondingly, there is also a need for automated continuous non-human data sharing, utilising core but confidential data feeds from hospitals, doctors’ surgeries, care homes, petrol stations, and supermarkets.

Theme 4: Prevention is better than Cure

There is a need to avoid social isolation of vulnerable individuals and catch them before they fall. For example, the credit dispossessed already need to be identified for compliance with the Digital Economies Act. Sharing this data appropriately would improve their self- resilience, digital exclusion, and community engagement, supporting the ‘Leave No One Behind’ promise².

Theme 5: Increased Inter-sector³ Collaboration

Identify key relationships and ensure collaboration exists at middle-manager level under normal circumstances. There are regional- and national-level requirements where situational awareness centres would be valuable. This would require multiple agencies to work together in true collaboration in order to achieve a nationwide view of data sharing involving industry sectors, trade bodies, regulators, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), HMRC, DWP, Local Government, Environment Agency, Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office, the Civil Contingencies Secretariat⁴ and DCMS.

Create localised groups – in the context of the current engagement approach to data sharing in local hubs – to radiate outwards and include other services – police, fire, local government, ambulance service, etc – and the wider Voluntary and Community Sector (VCS). This should be advocated across local regions and/or expand the existing charity- based Vulnerability Registration Service (VRS) hub for local utilisation between existing Local Resilience Forums (LRFs).

Ensure that previous ‘lessons learned’ are fed into a nationwide table-top exercise to include data sharing and supported with relevant training in a pre-emergency environment, and identification of process improvements.

Theme 6: Addressing Data Sharing

Greater understanding of appropriate data-sharing needs to be developed in ‘peacetime’ so that the relevant parties have developed experience of each other and will be better placed to trust each other in an emergency. For any VCS entity engaged in gathering data in an emergency, data ownership and handling considerations need to be pre-confirmed. Therefore, a standard playbook of protocols – for banks, for supermarkets, for volunteer bodies and the wider VCS – should pre-exist so that both pre- and post-event effective data sharing is normalised to achieve a human-centred approach, especially for those most vulnerable.

Ensure that any security obligations placed on third parties are obligations that you also adhere to on a day-to-day basis. Use the mechanism of conducting a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) to shape and evidence data sharing.

Theme 7: The Role of Technology

Technology is required to carry out data aggregation and data mining⁵ to support service provision. Where services are in agreement already, the reach needs to include the Police Service, Ambulance Service and beyond. Thereafter, integration of the energy sector is required.

The Tell Us Once⁶ service, available upon death, needs to be remodelled for life events and vulnerability to include affordability⁷ data, geographical information system data, and topographical research data from DEFRA. The result could be extremely powerful. This may require lobbying to align vulnerability checks with affordability checks. Licence conditions may be required in order to share the data. In the case of the public sector, the expectation of the reuse of Public-Sector Information (PSI) already exists.

Utilities need to talk to each other in order to achieve the regulator’s stipulated 80% target for PSR adoption. In the energy sector, interconnectivity of all the Distribution Operators in the UK is required. A senior-level roundtable may be required to improve the current landscape and adoption.

Widespread use of agreed, available industry-sector ‘Needs Codes’ is required, with tangible outcomes being driven by their use, and mapping to the Vulnerability Registration Service (VRS) as they increase in use. In particular, there is a need to consider how duplicates will be handled, who carries out data cleansing, and which dataset is considered to be the most up to date.

Theme 8: Horizon Scanning

The results of this project need to be considered in the context of the National Resilience Strategy⁸, the Public Value Agenda, and the National Data Strategy.⁹ For the private sector, these recommendations need to be considered in the context of both Environmental Social Governance (ESG) and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). The results also need to be aligned with other research work being undertaken by the National Preparedness Commission (NPC) and with the activities of the Data Collective¹⁰.

Policy co-ordination is required across the regulators, particularly Ofwat, Ofgem and ICO.

Identifying and mobilising core skills is vital. For example, an up-to-date register of qualified skilled personnel is required in the context of supporting the aftermath of major events such as Corgi-registered gas personnel or specialists in laying fibre optics, etc. It may also be necessary to consider the role of Category 1 and 2 responders, and adapt their training accordingly.¹¹

Complex Landscape

Background and Context

Since the evolution of electronic government, the UK Government has long been supporting an approach of positive data use. In September 2020 the Ministry of Justice’s Data First¹² included a National Data Strategy (NDS)¹³ which set out the framework for government action in support of unlocking the value of data across the economy. Under the NDS, data and data use are seen as opportunities to be embraced rather than threats against which to be guarded. The Government Data Quality Framework¹⁴ is a commitment made in the NDS under the Data Foundations pillar. The NDS recognises that by improving the quality of data, better insights and outcomes can be driven from its use. This framework provides government with a more structured approach to understanding, documenting and improving the quality of its data¹⁵. This approach needs to be cascaded through all sectors with multi-directional support and trust.

At the outset of the Covid-19 pandemic, there was hesitancy around how much data could be shared to ensure that vulnerable individuals could be supported in the community. To this end, in the late summer of 2021, the NPC undertook a short study investigating the practicalities of sharing data held on customers in vulnerable circumstances in order to best respond to a crisis in the context of the current data-protection legislation. The outputs focus on why data sharing is so vital, and explore scenarios where data sharing would have helped other organisations provide a better response.

Whatever approach is taken to data sharing¹⁶ suggests that with more advanced and complex uses of data, good communication with customers about who sees their data, how it is used, what the benefits are, and the data protection and assurance processes supporting it, become even more critical¹⁷.

Historically, firms have tended to rely heavily on strategies of self-disclosure, an approach that has worked effectively for identifying a subset of customer vulnerabilities, especially those that are static and unlikely to change over time. However, living through the pandemic has challenged individual perception of vulnerability and placed more people in that catchment than would be the case in normal times.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) requires those who are processing personal data to put in place appropriate technical and organisational measures to implement the data-protection principles effectively and safeguard individual rights. This is ‘data protection by design and by default’ and requires integration of, or ‘baking in’, data protection into all processing activities and business practices, from the design stage and throughout the lifecycle of the data use. This concept is not new – it was previously known as ‘privacy by design’. It has always been part of data-protection law. The key change with the UK GDPR is that it is now a legal requirement and the accountability principle requires those processing personal data to be able to evidence how they have protected it.

Priority Services Approach

The creation of PSRs is industry led rather than regulatory led. In the energy sector, having a PSR is a license requirement and this has improved the sector size and accuracy of the data. Smaller energy companies are slow to adopt this approach: the gas industry currently does not have one. Over 90% of customers are dual fuel so it could be that up to 10% of customers may not have any gas and thus may not have a related vulnerability requirement. There are fewer water companies than in other energy sectors and there is thus far less competition in that sector. Nonetheless, there are multiple PSRs all linked in the utilities sector with an easy opt in for customers. This should result in greater information sharing because of a common interest in achieving the required regulator-led improvement percentages. Whilst being institutionally similar, there is still a lack of data sharing. Induced competition requires collaboration.

The 2017 Strategic Policy Statement (SPS) sets out the priority and focus: current considerations include flood and drought management, population growth, increasing density, reducing leakage, etc. In the same year, the UK Regulators’ Network (UKRN), Ofgem and Ofwat published a report calling for greater cross-sector collaboration and the sharing of non-financial vulnerability data through PSRs.

In April 2021, the UKRN identified its Key Strategic Priorities, supported with several key networks focusing on Data Strategy, Vulnerability, and Climate Change. The UKRN has four core members – Ofgem, Ofwat, the Payments Systems Regulator, and the Regulator of Social Housing. Of these, Ofwat has made the most progress with regard to data sharing, with a specific non-financial, more reputational incentive requirement – the customer measure of experience (C-MeX). This rewards those who perform better on customer service and disincentivises those who do not. Ofwat has the power to fine¹⁸ water companies for poor data quality, and any inability to maintain data accuracy between systems. This signposts the need to understand the content of and reasoning behind data captured in all fields, and in all systems.

Identifying and addressing the needs of vulnerable customers have been key aspects for many industries for some time. This is largely achieved through the use of PSRs. There is a broad consensus amongst firms that knowing who their vulnerable customers are is an important first step in being able to ensure they get the support they need.

The water sector’s PSR approach is ahead, particularly through the efforts of Thames Water. Other utilities need to improve their usage of PSRs in order to achieve regulatory obligations. As this is not a competitive market, there is no disincentive to share best practice. Further communications to residents may be required, perhaps from doctors. Technology is already designed and operating effectively, funded by energy and power companies, using an engine which translates requirements into actions across various utilities and service providers. This is a not-for-profit approach and requires a subscription payment in order to maintain it. The system is not labelling individuals as vulnerable, rather identifying their needs and assigns a numeric value (code) to it. The resulting Needs Codes derive actions so the need (vulnerability) itself is not shared. The actions are communicated via data flows.

There are some additional fields available relating to the household (such as alternative emergency contacts) and a small number of specific Needs Codes. An example is that if ‘Unable to communicate in English’ is flagged then it instigates a language requirement data flow. This is set across systems as a drop down to prevent typos and lazy data entry (i.e. putting a full stop in to populate a field). On this drop down is also the language for the deaf: the National Association of Deaf People advised of distinctions between deaf from birth versus deaf as a result of a disease or other life event, which results in the need for a different service level.

The Changing Face of Vulnerability

Cabinet Office guidance¹⁹ defines a vulnerable person as ‘a person less able to help themselves in the circumstances of an emergency’. The London Resilience paper²⁰ articulates some of the challenges of data holdings across a number of involved parties:

- Local Authorities;

- National Health Service (NHS);

- Emergency Services;

- Utilities (Electricity/Gas/Water);

- Voluntary and Community Sectors.

Following the Covid-19 pandemic, there is concern about the burgeoning mental-health crisis, in particular across the youth population. Vulnerability is not static. In fact, in some cases, customers may be offended by the term vulnerable. The use of a PSR allows for temporary situations, providing support in those circumstances. In the electricity industry, a quarter to a third of individuals are classed as vulnerable.

In the case of the VRS, there are a number of different flags for vulnerability:

| • Physical health | • Mental health |

| • Financial hardship | • Serious financial hardship |

| • Capability | • Disability |

| • Covid-19 | • Coercion |

| • Debt Management | • Lifecycle event e.g. bereavement, divorce |

Equally, there are different categories of people in an event – injured survivors, non-injured survivors, family, friends, witnesses, etc. All of their needs must be considered.

Pregnant women were classed as vulnerable during the pandemic but this would not normally be the case or may that be the case in the future. Thoughtful consideration regarding situational vulnerability is required.

Given the need to consider future risks and applying lessons learned, the significant changes in the geopolitical landscape experienced in August 2021, increase vulnerability to radicalisation and Incel activity was of heightened consideration. There is invariably an available data trail that should be being actively monitored and, in certain circumstances, wider data sharing would illuminate activities of note.

Perceived Data-sharing Barriers

Although the current data-protection legislation makes provisions for situations where a person’s ‘vital interests’ are at risk (i.e. when you must process personal data to protect someone’s life), there is a perception that it can be hard to apply these principles to concrete emergencies. Lack of clarity over which data can be shared can lead to a fragmented awareness of who is at risk and who is affected, which may delay crucial interventions. For example, after the Manchester Arena attack, those co-ordinating the mental-health response wanted to reach out to all ticket holders, yet getting hold of and preparing the data took about 10 weeks. Whilst this did not delay timelines as clinical guidelines at the time recommended an initial period of watchful waiting before reaching out, nevertheless, it reveals considerable hurdles in data sharing in an emergency response.

Reluctance to share data may mean that victims are not helped as quickly as they could be or are asked to recount their story several times, which can feel unnecessarily re- traumatising. Similar issues were at play in the aftermath of the 7/7 bombings in London in 2005.²¹ Partially in response, the 2007 guidance on data sharing in emergencies was published by the Civil Contingencies Secretariat (CCS) which seeks to make it easier to share data in an emergency. Whilst the ICO has laid out a number of principles as guidance, there is a belief that these do not go far enough.²²

With inadequate data sharing, different services can operate under different estimates of need or volume of people affected in an incident. It can also cause duplication of information gathering across organisations, ultimately having resource and financial implications.

The Data Protection Act (DPA), the Human Rights Act and the Common Law Duty of Confidence are all cited as reasons not to share. It depends on what is shared because these laws protect individuals and if anonymised (or aggregated) data are shared then they are not applicable e.g. the sharing of Needs Codes with their corresponding action requirements rather than any personal identifiers. There are also laws that protect specific types of data, Council Tax for example. As long as an organisation processes data lawfully and fairly then there is no barrier to sharing.

Management of risk requires accuracy of conclusions being reached from available data; actions taken as a result of those insights could result in political fallout.

Public Expectation, Scenario Setting

Public Perception

During the UK response to Covid-19, the public had a lack of understanding as to how the ‘shielding’ lists²³ were compiled. In some cases, the shielding letter was received direct from central government before local government knew about them. This proved unhelpful in the provision of local services. The time and effort involved in list compilation were not fully understood or appreciated. Public expectation is based on an assumption that various institutions are already sharing data and/or that the systems involved in core government data collection are linked to other platforms to reduce duplication of data entry, including across health and social-care providers.

There is a trust and perception disjoint between the public and service providers across all sectors. The expectation is that they are acting in the public interest and thus do not require to seek consent to share data in the event of an emergency. If, as a worried citizen, an individual would share their data, and that of others, in order to seek a positive outcome then there should be an equal expectation that any particular regulated industry body, emergency service or other public-sector entity should be able to share the same data i.e. sharing as @LondonFireBrigade instead of @hotmail should not present any challenge.

Scenarios and Data-sharing Use Cases

The Smart Data Working Group publication in Spring 2021²⁴ set out a series of customer journey, user cases across multiple sectors. The research participants²⁵ engaged in this NPC study articulated a number of different scenarios, set out below. The corresponding data-sharing opportunities or challenges are signposted.

An individual on furlough could be likely to miss a mortgage payment. This may result in stress, anxiety, etc.

Data-sharing opportunity: If the bank shared knowledge of an individual’s situation with their GP surgery, with a corresponding flag on their record to show increased vulnerability, and also with the service companies that the individual already has relationships with, this could pre-empt further debt. Early intervention could improve their health and wellbeing. It is better to catch people ‘before they fall’.

Around £110m was given out in government grants to Suffolk County Council (SCC) but central government then complained that SCC had only spent £71m and queried the delay in distributing the available funding. SCC had identified that the funding was going towards the purchase of new beach huts in Suffolk – an inappropriate usage of public-sector funds. Hut owners set these up as second homes under a small business exemption and, by renting them out, were claiming corresponding tax relief.

Data-sharing challenge: Every positive system that is created has the potential to generate a negative outcome during its implementation and operation.

Gas personnel in the homes of shielding residents found that a blind person was unable to see if they were wearing their PPE or keeping their distance. This created trust issues and increased the feelings of vulnerability. Without the shielding information, they were not as well prepared as they could have been in order to provide better reassurance to customers in a difficult and scary situation.

Data-sharing opportunity: Ensuring the regular and easy capture of customer need(s) and also being able to signpost having put those needs into tangible action and/or changes for service provision.

If a person has restricted hand movement e.g. because of arthritis, it can be difficult to turn off a stop cock in the event of an emergency. In the case of one service provider, they have a new, innovative EasyAssist Emergency Control Valve (ECV)²⁵ push button that will alleviate the risk of this emergency situation creating a more unfortunate customer outcome.

Data-sharing opportunity: This may not have previously been considered a vulnerability (or need) but something a provider may have a solution and it is therefore sufficient to warrant inclusion on the service provider’s PSR and thus the provision of priority service(s).

A patient leaving hospital and being sent to a care home could have nut allergy mentioned on their discharge form but on contacting the Ward no staff members had any awareness of this. Depending on the severity of the allergy, this lack of data sharing could have fatal consequences.

Data-sharing opportunity: Accurate discharge notes need to be made available to care homes in a timely manner for better patient care and outcomes.

In the case of delivery of food, prescription drugs, and Huggg²⁶ (welfare) vouchers, there was fraudulent activity.

Data-sharing challenge: This was another example of a positive system also generating a negative outcome, irrespective of effective data sharing which can impact the ability of cash-strapped organisations to continue to operate.

After the London bombings on 7 July 2005, Experian worked alongside the National Terrorist Financial Investigation Unit (NTFIU) providing intelligence following a deep dive of the available data repository. At the time, this required extra staffing to run 24×7 data analysis. It was possible to identify suspects retrospectively. Obviously, the key task was to be able to identify them in advance.

Data-sharing opportunity: Current anti-money laundering (AML) practices might identify such anomalies now. If ‘[email protected]’ exists as an email address in the system, identifying this can generate a level of subjective thinking. Review of related identities, associations on joint applications, aliases for credit applications, phone numbers, aliases for other purposes, IP addresses, etc, are then subject to ongoing monitoring and checking against the Electoral Roll to identify how many people were at the same address. Payment history and unusual behaviour were tracked and monitored to provide intelligence, and not just from a fraud perspective. Lending decisions can also be considered given that fraud-prevention products are helpful but there have been multiple links to charities. Small money transactions are often more about identity creation; stolen proof of identities is often used. The tech-savvy criminal knows how to apply for their credit reports. This is a multi-organisational, bi-directional data-sharing landscape opportunity between credit- reference agencies, financial-services organisations, local authority electoral rolls, etc.

Following the Grenfell fire, the British Red Cross (BRC) was engaged to help the triage of residents in a nearby local facility. As a charity, they were offering themselves for support without agenda or consequences. Data-sharing challenge: There were instances where individuals were hesitant to share their personal data, not wanting the authorities to know they were in residence.

Data-sharing opportunity: Charity organisations need to be able to freely share data with the emergency services. As mentioned elsewhere in this report, the need to do so in peacetime is paramount in order to ensure that doing so in an emergency is not met with cumbersome process overheads or other unforeseen barriers.

There have previously been situations in which information about the death count following an emergency was not shared, to the extent that different services were operating under different estimates.

Data-sharing opportunity: Ease of sharing between emergency services and other VCS bodies is required. This takes relationship management, the will to do so, and an understanding that everyone is operating within the same data-protection legislative context.

Lesson Learned

Theme 1: Data-sharing Issues and Challenges

During the recent pandemic, whilst everyone was clamouring for access to shielding data, it was not always clear whether there was an identified need or purpose in any requests for access to it.

There is an abundance of data-sharing guidance available from both the ICO and across all sectors. The updated data-protection legislation landscape did not fundamentally change what could or could not be done with regard to data sharing in any emergency situation or in regard to the provision of services to the particularly vulnerable. Any paralysis is through a perception of difficulty rather than any reality. The inability to see a way forward is hindering progress with regard to data sharing and data insight.

Supermarkets were provided with the shielding data in the pandemic as part of the effort to ensure delivery of key services, where provision of food (and toilet paper!) was prioritised as a critical need over the provision of gas, power (for heat), water, etc. Many VCS organisations attempted to work together to co-ordinate identifying needs, accessing supplies, and processing and delivery logistics. These were hugely impacted by the inability to pass information freely between organisations.

Whilst many organisations are focused on the identification of customer vulnerability, the collection and use of data are not consistent across water, telecoms, electricity, energy, etc. There is a patchwork of bi-local agreements between local councils, fire brigades, etc, including Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) with statutory agencies. A pan-London Data Sharing Agreement is being worked on; a simple DPIA has also been created. These outputs should be shared and modelled in order to reduce time being spent on multiple iterations being created across all industry sectors.

Time taken up on getting legal approval for data sharing agreements can hamper effective data sharing and customer resolution.

Amongst others, the BRC is not always included at the strategic LRF meetings or with the statutory agencies when post-incident review is taking place. The BRC has a global reputation and is part of a Rapid Deployment Team in the event of an emergency. It has a contract in place with government and a remit under the Geneva Convention to perform an unchallenged auxiliary role. It may need to use this more to improve trust and two-way data flow.

Theme 2: Vulnerability Registers

Charities do not know to reference the VRS or the PSR. The Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB) asked Cadent for their shielding data but this comes from the NHS so it was not held by the utility.

Local Authorities have a mandate to work with the VRS but adoption is slow. There are only about 60,000 records on the register at the moment.

Whilst water and energy utilities are now using the same codes (after 18 months of dialogue), their existence was unknown by the Fire Service.

If an engineer has to visit in an emergency then any further household-related data gathered on site are fed back into the system to afford the addition of further safeguards that maintain an outcome-based system in order to better react, respond and support the household.

In the case of one energy provider, its Innovation and Insight Team has built a vulnerability index using open data from NHS Trusts and Care Quality Commission (CQC) data. The number of care homes in an area indicate age, demographics and potential vulnerability status. There is a lack of mapping of hotspots for most vulnerable people in other regions.

‘Utilities against scams’²⁸ helps to protect individuals, particularly those that are vulnerable. Most utility companies produce helpful Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) sections²⁹ that address any customer concerns with regard to their participation and registration on a PSR.

Theme 3: Skills and the Unknown

Event-management personnel have been used to resource temporary mortuaries during the pandemic. They have been working in traumatic circumstances. For most of them, this experience will have been far beyond their previous working environment. They are being offered ongoing support for that, which is also a new arena for service provision.

The care-home industry is further behind in terms of digitalisation of records. Up to half of care homes may struggle to engage because of a lack of prioritisation of data handling and thus investment. For example, once a resident dies, the family may require all of the records relating to the deceased in order to contest funding. In a short-staffed and stretched environment, this level of manual data handling can take up to three days to find all the required records, scan them and provide in a suitable form to the requestor. The care fees do not cover this kind of administrative data-related activity. Care England and National Care Association receive complaints regarding the lack of correct information being shared by all providers.

Lessons have been learned from previous events (e.g. Grenfell, 7/7 bombings) but these do not appear to have been acted upon. There is a need to feed the lessons learned into a large-scale, table-top exercise, to include data sharing, and supported with relevant training in a pre-emergency environment.

In order to provide volunteers at multiple testing and vaccination sites, many different formal charitable organisations and informal community groups were stood up. Organising, managing and ultimately sharing volunteer resources to meet protracted needs were reliant on the sharing of contact and personal details of willing volunteers. This has been a blocker in some instances where a testing or vaccination site has only been able to rely on a single provider of volunteers.

Unknown unknowns are rarely unknown. Previous resilience planning had taken into account the possible scale of death in a pandemic, and the likelihood of the NHS being overwhelmed. However, lockdowns and shielding requirements along with social distancing, etc, had not been foretold.

Towards National Data Sharing

Legal Powers

Proactive data sharing was already possible. A legislative requirement to comply with the law, and available Codes of Practice, exists. The expectation is that all data controllers and processors are only processing data for specified purposes, irrespective of the lawful basis. Any data sharing should already be covered in the Record of Processing Activities (RoPA) – a GDPR mechanism. Any Data Sharing Agreement (DSA) is usually structured for a single specific purpose rather than for broad sweeping data sharing.

In every case, any participants in a data-sharing relationship need to be able to evidence whether the data sharing would be considered to be:

- either reasonable or necessary³⁰; and

- proportionate to the work being done.

The ICO description of ‘is necessary’:

Many of the lawful bases for processing depend on the processing being ‘necessary’. This does not mean that processing has to be absolutely essential. However, it must be more than just useful, and more than just standard practice. It must be a targeted and proportionate way of achieving a specific purpose. The lawful basis will not apply if you can reasonably achieve the purpose by some other less intrusive means, or by processing less data.

It is not enough to argue that processing is necessary because you have chosen to operate your business in a particular way. The question is whether the processing is objectively necessary for the stated purpose, not whether it is a necessary part of your chosen methods.’

Data-sharing participants must be able to:

- identify a vulnerability that justifies the data sharing – demonstrate you have a need to see it;

- evidence what services are being provided to the customer as a result of the identified need;

- ensure that you have the right systems in place to support this, including exception management;

- ensure that customer complaints are tracked, monitored and resolved, with any resulting system amendments required taking place;

- ensure that your outcomes are support focused; and

- ensure that the quality of the resulting datasets is measured and maintained.

In the event of any emergencies, flash floods or major outages, a clear legal power to share data exists. Under the regulations made under the Civil Contingencies Act 2004 (CCA) (the (Contingency Planning) Regulations 2005, Regulations 45 to 54), there is a duty on Category 1 and 2 responders. Where such responders reasonably require information held by another Category 1 or 2 responder in connection with the performance of their duties or functions then such information (including personal data) may be requested and that the responder receiving the request must comply and share such information unless an exemption applies. This duty relates to the response and recovery stages of an emergency (i.e. emergency preparedness) and civil-protection work so the data sharing is time and purpose bound.

Under the Fire & Services Act 2004, Section 5, the Fire Service has powers and no limit to the number of ‘removes’ to act.

Actions taken under the CCA, in accordance with the data-sharing requirements of the Contingency Planning Regulations, will be compliant with data-protection legislation if:

- a legitimising condition is met;

- information is being shared for a specific purpose;

- information is being shared for a limited time;

- information is only to be shared between named Category 1 and 2 responders that have a defined (as assessed by the requesting organisation or individual) need to see it; and

- the data subjects are informed that their data may be shared within government for emergency response or recovery purposes unless to do so involves disproportionate effort.

However, processing may be considered to be unlawful if it results in:

- A breach of a duty of confidence;

- Exceeding legal powers;

- An infringement of copyright;

- A breach of an enforceable contractual agreement;

- A breach of industry-specific legislation or regulation; and

- A breach of the Human Rights Act 1998

Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) guidance explains that in the context of safeguarding economic wellbeing, a substantial public interest condition may be relied upon when processing (which includes recording and sharing) health data without the customer’s consent.³¹

A Liability Framework is already articulated in the Ministry of Justice work previously referenced herein.

In 2014, the Law Commission laid down a report before parliament titled ‘Data sharing between public bodies’³². This was prior to the laying down of the 2018 data-protection legislation updates and amendments. The combined data-protection law is the data- sharing model.

Data-sharing Agreements

The creation of a partnership agreement or equivalent data- or information-sharing agreement can be useful but this is not a necessary requirement. If all parties are governed by the prevailing data-protection legislation then the expectations of accountability are inherent. However, although there is no law that explicitly says a DSA must be put into place, the Accountability Principle of the GDPR requires that reliable records are created for all data–processing activities. Therefore, having DSAs in place for data-sharing relationships can be considered to be part of demonstrating compliance with data-protection law³³.

There are many examples of DSAs available across all industry sectors. These have received legal review and are supported by advice and guidance from many existing data protection officers.

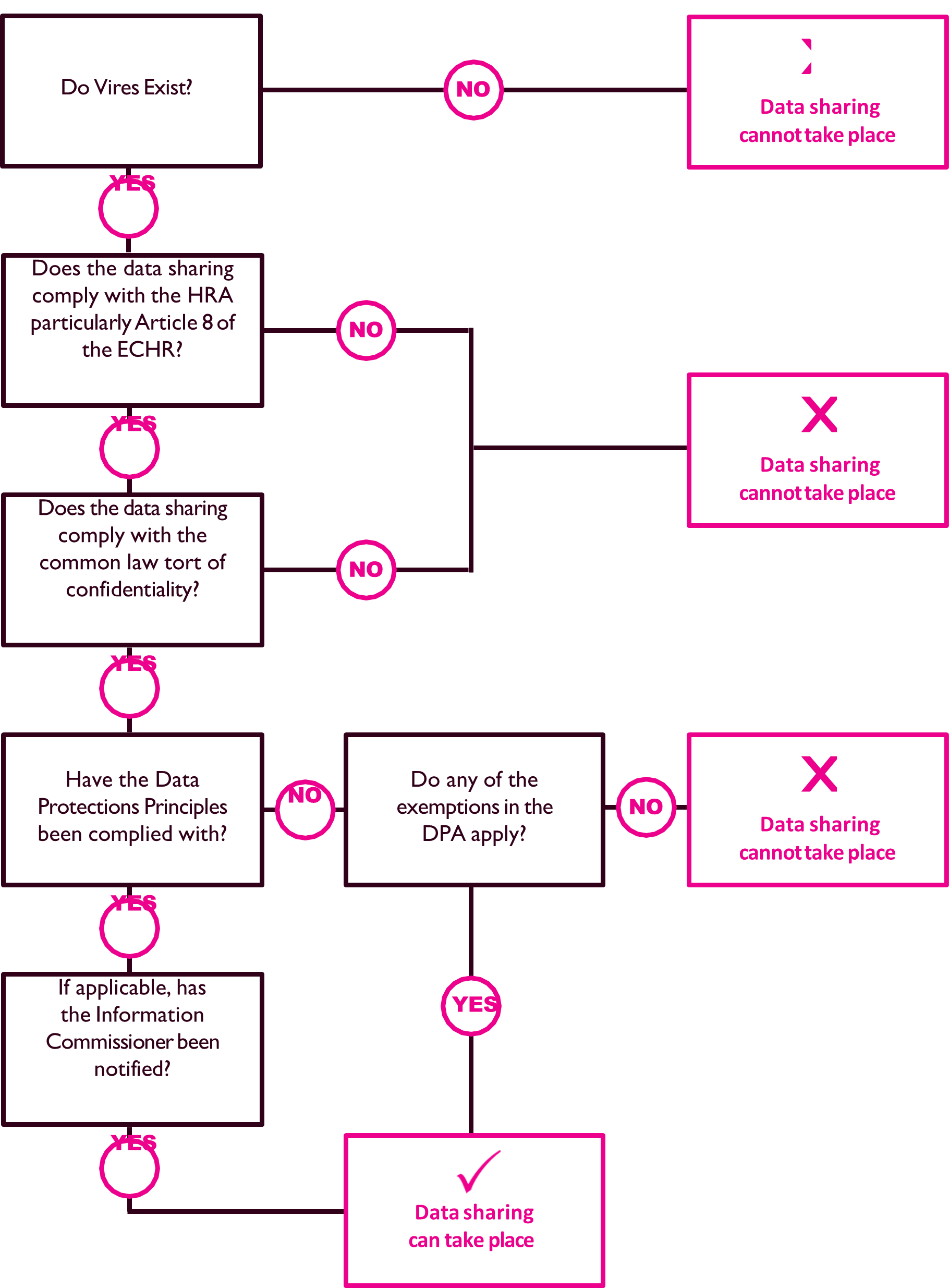

The checklist below provides relevant legal considerations relating to data-sharing partnerships.³⁴ This is supported by a decision tree on page 28.

Vires Issues

- Does the body that is to hold and administer the database (the ‘data controller’) have the vires to do so? Careful consideration needs to be given to the existing legal powers that each body has and whether these powers extend to the holding and operation of the new database.

- Is the existing data that is to be shared subject to relevant statutory prohibitions whether express or implied?

- Even if there are no relevant statutory restrictions, do the bodies sharing the data have the have the vires to do so? This will involve careful consideration of the extent of express statutory, implied statutory and common law and prerogative powers, if relevant.

- If there is no existing legal power for the proposed data collection and sharing then consideration should be given to establishing a statutory basis by enacting new legislation.

Human Rights Act 1998 Issues

- Is Article 8 of the Human Rights Act (HRA) engaged e. will the proposed data collection and sharing interfere with the right to respect for private and family life, home and correspondence? If the data collection and sharing are to take place with the consent of the data subjects involved, Article 8 will not be engaged.

- If Article 8 of the HRA is engaged, is the interference (a) in accordance with the law;

(b) in pursuit of a legitimate aim; and (c) necessary in a democratic society?

Common law duty of confidentiality issues

- Is the information confidential e. does it (a) have the necessary ‘quality of confidence’? (b) was the information in question communicated in circumstances giving rise to an obligation of confidence? (c) has there been an unauthorised use of that material? Consider here whether the information has been obtained subject to statutory obligations of confidence. If the data collection and sharing are to take place with the consent of the data subjects involved, the information will not be confidential.

- If the information is confidential, is there an overriding public interest that justifies its disclosure? The law on this aspect overlaps with that relating to Article 8 of the HRA.

Data-protection Issues

- Does the DPA apply e. is the information personal data held on computer or as part of a ‘relevant filing system’?

- If the DPA applies, can the requirement of ‘fairness’ in the first Data Protection Principle be satisfied?

- Can the requirements of compatibility that is in the second Data Protection Principle be complied with?

- Do any of the exemptions that are set out in the DPA apply?

Relevant Considerations for Lawful Sharing of Personal Data*

Key Principles and Benefits of Data Sharing

Data-protection legislation does not prohibit the collection and sharing of personal data; it provides a framework where personal data can be used with confidence that individuals’ privacy rights are respected. ‘Dare to share’.

Greater use of and reliance on the available Data Protection Officers are essential. Their role, by law, is to provide advice and guidance.

Move away from consent. The consent of the data subject is not always a necessary pre- condition to lawful data sharing. There are five other grounds for legal data sharing.³⁵

Always check whether the objective can still be achieved by passing less personal data. This reduces the burden on all parties to the sharing, to protect and maintain the data safely and securely.

In emergencies, the public-interest consideration will generally be more significant than during day-to-day business, alongside health and safety legislative measures that exist.

Emergency responders should be robust in asserting their power to share personal data lawfully in emergency planning, response and recovery situations.

Emergency responders should balance the potential damage to the individual (and where appropriate, the public interest of keeping the information confidential) against the public interest in sharing the information.

Make every contact count – data sharing reduces effort on everyone, from those customers who benefit to organisations that need to be proactive during a crisis.

Ensure awareness of the need to disclose vulnerability and share data – people do not know about the benefits of disclosure of their situation, often because crises are infrequent.³⁶

All Data Controllers must apply appropriate organisational and technical measures to protect data. Effective utilisation of technology improves processes, and can reduce the data-provision burden on statutory bodies and third sector; the latter consists of organisations in a better position to engage with those who are seldom heard and hard to reach. Smoothing the data-sharing channels will protect the customer, their data and their health.

References and Resources

1 See Sections 3.5 and 3.8 page 9 and 11.

2 Leave no one behind (LNOB) is the central, transformative promise of the 2030. Agenda for Sustainable Development and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – see https://unsdg.un.org/2030-agenda/universal-values/leave-no-one- behind

3 Public, Private, Voluntary, etc.

4 Civil resilience categories – i.e. hotels, schools, hospitals, care homes.

5 This already exists within the Thames Water Auriga system offering.

6 Tell Us Once – LGA – https://www.gov.uk/after-a-death/organisations-you-need-to-contact-and-tell-us-once – bereavement / death

7 Affordability checks are there to make sure that an individual can afford the repayments on any particular financial product or loan repayment scheme applied for. A poor result on an affordability check could see the lender being unable to proceed with your application and may even affect your chances with other lenders too.

8 https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/national-resilience-strategy-call-for-evidence https://nationalresilience. citizenspace.com/rst/resilience-strategy-call-for-evidence/

9 https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/national-resilience-strategy-call-for-evidence; https://nationalresilience. citizenspace.com/rst/resilience-strategy-call-for-evidence/

10 https://data-collective.org.uk/2021/07/21/leadership-data/

11 In the case of hurricane planning in the US, white-collar workers have a dual role; 7,000 personnel were mobilised to help move trees, etc, following Storm Henri in August 2021. Emergency contractors in the US are well paid. This concept could be the equivalent of ensuring that there is a level of retainer applied to Category 2 responders in the UK.

12 https://www.gov.uk/guidance/ministry-of-justice-data-first

13 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-national-data-strategy/national-data-strategy

14 Government Data Quality Framework.

15 The British Red Cross briefing paper, August 2021.

16 https://www.ukrn.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/UKRN_Literature-Review_200320.pdf

17 The British Red Cross briefing paper, August 2021.

18 https://news.sky.com/story/thames-water-agrees-11m-compensation-after-customers-overcharged-12385154 – £11m fine over billing blunders?

19 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/61228/vulnerable_ guidance.pdf

20 London Resilience.

21 ‘Limitations on the initial collection and subsequent sharing of data between the police and humanitarian support agencies hampered the connection of survivors to support services like the Assistance Centre. The concern at the time was that the Data Protection Act might prevent the sharing of personal data without the explicit consent of those concerned. As a result, there were delays in information reaching survivors about the support services available’.

22 By 2019, the ICO had prepared a pdf listing all of the data protection guidance updates, etc, that they had carried out.

23 At the start of the pandemic, anyone considered at much higher risk from COVID-19 was asked to shield. People were regarded as clinically extremely vulnerable if they were at very high risk of severe illness as a result of coronavirus (COVID-19), and had a greater chance of being admitted to hospital. Shielding was introduced as a way to protect the most vulnerable from serious illness from the virus.

24 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/smart-data-working-group-spring-2021-report

25 See Appendix A.

26 https://youtu.be/P0saHLfmdW0

27 https://www.huggg.me/

28 https://cadentgas.com/help-advice/supporting-our-customers/uas-be-scam-aware

29 See Appendix B.

30 https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-data-protection/guide-to-the-general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr/ lawful-basis- for-processing/#when

31 Financial Conduct Authority, Guidance for firms on the fair treatment of vulnerable customers, FG21/1, Appendix 1 p.50.

32 https://www.lawcom.gov.uk/project/data-sharing-between-public-bodies/

33 https://www.lmc.org.uk/visageimages/guidance/2019/DSAchecklistguidanceV1.1Final.pdf

34 Public sector data-sharing guidance on the law, Department for Constitutional Affairs, November 2003.

35 The law provides six legal bases for processing: consent, performance of a contract, a legitimate interest, a vital interest, a legal requirement, and a public interest.

36 The average water supply interruption of over 3 hours is rare – around a 1-in-7 year event.

Further Reading

BritainThinks (2020) The Challenge of identifying vulnerability: a literature review, a UKRN report, 20th March 2020.

Available at: https://www.ukrn.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/UKRN_Literature- Review_200320.pdf

British Academy and The Royal Society (2017) Data Management and Use: Governance in the 21st Century, Available at: https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/projects/data-governance/data-management- governance.pdf

Cabinet Office (2008) Identifying People Who are Vulnerable in a Crisis: Guidance for Emergency Planners and Responders.

Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/61228/v ulnerable_guidance.pdf

Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (June 2021), Smart Data Working Group: Spring 2021 report.

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/smart-data-working-group-spring-2021- report

Department of Communities and Local Government (2014). Understanding Troubled Families, July 2014.

Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/336430/ Understanding_Troubled_Families_web_format.pdf

Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (2020) National Data Strategy.

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-national-data-strategy/national-data-strategy

Financial Conduct Authority (2021) Finalised guidance FG21/1 Guidance for firms on the fair treatment of vulnerable customers. Available at: https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/finalised-guidance/fg21-1.pdf

Government Data Quality Hub (2020) The Government Data Quality Framework – Guidance. Available at: https://www. gov.uk/government/publications/the-government-data-quality-framework

HM Government (2007) Data Protection and Sharing – Guidance for Emergency Planners and Responders, ISBN: 0711504784.

Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/60970/d ataprotection.pdf

Information Commissioner’s Office (2019) Guide to data protection.

Available at: https://ico.org.uk/media/for- organisations/guide-to-data-protection-1-1.pdf

London Resilience Partnership (2019) Identification of the Vulnerable: A Guidance Note for Local Implementation, Version 2.0

Redcross (2021) Briefing paper on Data Sharing Challenges, Ellen Tranter, August 2021 UK Ministry of Justice (2020) Ministry of Justice: Data First – Guidance.

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/ministry-of-justice-data-first

UKRN (2021) UKRN Annual report and multi-year workplan.

Available at: https://www.ukrn.org.uk/wp- content/uploads/2021/03/UKRN-workplan-and-annual-review-2021-for- publication-.pdf

Appendices

Appendix A: Research Participants

The researcher is grateful for the willing and interested participation of the following bodies:

| Sector | Body |

| Emergency Service | London Fire |

| Government Regulator | Ofgem |

| Government Regulator | Ofwat |

| Government Regulator | UK Regulators Network (UKRN) |

| Health and Social Care | Crystal Care Services Ltd |

| Local Government | London Resilience Forum |

| Local Government | Suffolk County Council |

| Utility | National Grid |

| Utility – Gas | Cadent |

| Utility – Water | Thames Water |

| Voluntary and Community | British Red Cross |

| Voluntary and Community | Vulnerability Registration Service |

Appendix B: Customer Q&A

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) have been prepared for a number of existing suppliers. See:

- https://wwutilities.co.uk/services/safe-warm/priority-customers/priority-services- register/priority- services-register-frequently-asked-questions/

- https://edfenergy.com/content/priority-services-register-frequently-asked- questions

- https://cadentgas.com/help-advice/supporting-our-customers/priority-services- register

- https://westernpower.co.uk/customers-and-community/priority-services/ priority-services-faqs/

- https://westernpower.co.uk/customers-and-community/priority-services/ priority-services-faqs/

Why are you sharing my data?

In order for us to ensure that you are safe, warm and independent in your home, there must be a reasonable expectation that we will share your data. Your health and safety and wellbeing are why we share the data. Your consent is not required. However, your agreement, understanding, willingness and co-operation are required in order for us to better provide you with appropriate ongoing services.

How are you protecting my data?

We have a legislative requirement to comply with the law and, therefore, would be protecting the data and only processing it for specified purposes, irrespective of the lawful basis.

What happens after an engineer visits my home?

If an engineer has to visit in the event of an emergency then any further household-related data gathered on site is fed back into the system to afford the addition of further safeguards maintaining an outcome-based system in order to better react, respond and support the household.

Who will you share my data with?

In most cases, the answer to this question will exist within the publicly available Privacy Notice for every organisation – where there already exists a legislative obligation to do so.