Societal Resilience Initiatives During Covid-19

Key Findings Research

Introduction

This report showcases how 15 initiatives delivered value to their local communities during Covid-19. It summarises the findings of research that was supported by the National Consortium for Societal Resilience [UK+] and funded by The JRSST Charitable Trust, examining initiatives as case study examples of societal resilience during the Covid-19 pandemic. The research looked not only at what was done, but also how value was delivered and how individuals stepped up in the face of unprecedented challenge to meet local need. This summary highlights the factors which were found to influence the success of the case study initiatives, demonstrating societal resilience built through partnership working and the importance of leadership, strategic design, co-ordination, communication, intelligence, management skills, and project delivery.

Though the nature, purpose and configuration of the case studies varied, six key factors emerged from the research as being influential in the success of the initiatives:

- The leadership and strategy that informed the design of the project’s co-production partnerships was important, building on a common purpose to support the delivery of community resilience throughout Covid-19. This included ‘intrapreneurial’ leadership within local government which involved introducing online systems at speed and implementing innovative strategies to work with local volunteers who were the delivery arm for community resilience, and business

- Working in partnerships to co-produce local initiatives actively drew on existing levels of trust in project partners and embraced principles of democracy and participation.

- The co-ordination and communication strategies applied to the recruitment, training, motivation and retention of mutual aid groups and spontaneous volunteers varied across the case study Adapting these strategies to local context served to minimise risk in activities.

- The initiatives developed varying strategies in relation to how they rapidly gained local intelligence from across the different partners and subsequently used that intelligence to meet local Maintaining the flow of local intelligence and maintaining the motivation of volunteers worked effectively through ‘informal situational trust’.

- Management systems were innovative in their inclusive design, including agility in managing safety, and consistency in enabling a rapid response to the changing landscape of Covid-19.

- Co-production in design of the delivery of initiatives helped to reach some of the most vulnerable in society, including hard-to-reach groups and families in poverty.

These factors are explored in more detail later in this report.

The Case Studies

The 15 case studies were selected to demonstrate a range of good practices from partners in the National Consortium for Societal Resilience [UK+]. They were explored through semi-structured interviews with 22 leaders and senior workers who were closely involved in the selected initiatives.

Case studies 1-8 were led by local government:

1. Somerset Local Authorities: Vulnerable People and Community Resilience (VPCR)

This innovative Covid-19 Community Resilience project recognised the need to respond rapidly to support the needs of vulnerable people in Somerset, with a particular focus on health, well-being and food support that met a range of cultural need as well health dietary requirements for the most vulnerable. The multi-agency initiative quickly established itself by involving volunteer delivery partners to connect the right people and organisations to the right local people, as well as implementing a centralised system of communications and information.

2. The Integrated Strategic Design of Bedfordshire Local Emergency Volunteers Executive Committee (BLEVEC) and Community Emergency Response Teams (CERT)

During Covid-19, BLEVEC and CERT responded rapidly to deploy volunteers to help with a range of tasks. The recruitment of volunteers is aligned to their partner network, which includes 55 organisations, 10 emergency faith providers, and 41 independent volunteers. By integrating the strategic and operational capabilities this design provides a 24/7 networked response which enables CERT volunteers, who are monitored by BLEVEC, to support emergency planners and emergency services across Bedfordshire towns and villages.

3. North Yorkshire Local Resilience Forum (LRF): Ready for Anything programme

During widespread flooding in North Yorkshire, particularly in the City of York, members of the public contacted North Yorkshire County Council to offer help. Aware that they had no official system to work with spontaneous volunteers, emergency responders had to turn them down. Gaining funding for two years for a pilot study, the City of York designed an approach to incorporate official volunteers into their response system. Business was included from the start with a focus on supporting each other during disruptive events. The project design covered the whole of the North Yorkshire LRF area.

4. Community Resilience Programme: – ‘What If’ – You can make a difference (West Sussex)

Established as a grass roots project in 2011 following significant flooding, ‘What If’ is a thriving volunteer innovative programme located in West Sussex County Council that supports community resilience and is indirectly linked to West Sussex Fire & Rescue Service. It aims to empower local communities to help themselves and the most vulnerable during disruptive emergency events, but also promotes a greater community cohesion and resilience by their visibility in the community and their commitment to value the volunteers in their day-to-day activities. Volunteer training is available to learn about preparedness, response and recovery.

5. Lincolnshire LRF Covid-19 Action Groups: Communities Resilience Programme

A pressing issue for the LRF, and all emergency services, is how to first identify the range of volunteers that present themselves and then to manage expectations, especially of those volunteers who spontaneously turn up at an emergency, such as a flood, but cannot be effectively deployed for safety reasons. The LRF developed a strategy for the volunteers to form local community action, harnessing their valuable hyper-local knowledge and relaying it directly to the LRF during an emergency. Regular engagement with volunteers established strong working relationships and the impetus for the transformation of two mutual aid groups to charity status as well as establishing a food bank.

6. Cumbria LRF: A Strategic Approach to Community Resilience: Working Together in Partnership

Cumbria’s strategic approach to community resilience is an ongoing programme of work rather than a project. Prior to Covid-19 a key aim had been to close the gap between the communities’ response and statutory sector responders so that they could embed trust by working together as equals and develop a co-ordinated response. As well as supporting community emergency planning, this linked to wider transformation programmes in local public sector organisations, aiming to influence organisational policies, and support staff to become more comfortable working with informal community groups, including the many mutual aid groups that developed during the pandemic.

7. Eastleigh Borough Council, West Hampshire, Covid-19 Local Response

At the start of the Covid-19 pandemic a key feature of Eastleigh Borough Councils’ response was to ask spontaneous volunteers (SVs) and mutual aid groups, who were rapidly forming in the community, if they would work together with them on an equal footing, to provide support to the vulnerable in their communities. The consistent presence of LRF representation in the community and online motivated the public response to support social need and presented an opportunity for the Council to recruit these volunteers as a delivery arm for their Covid-19 strategy.

8. Essex County Council, and its Community Campaign Model for co-production

One of a number of Covid-19 projects that Essex County Council commissioned to provide support for their residents was based on a Community Campaign Co-Production Model. An in-house partnership was established between Strengthening Communities, Essex Wellbeing Service, Operation Shield and Emergency Planning. The vision included a distinct type of volunteer recruitment and a depth focus on communities informed by eight core Community Campaign Model principles. These were developed around: place; interest; identity; community influencers; involving community input in decision-making; digital innovation for community support and volunteer recruitment; where to add value; and maintaining a shared mission.

Case study 9 was led by a big business in partnership with its community and local government:

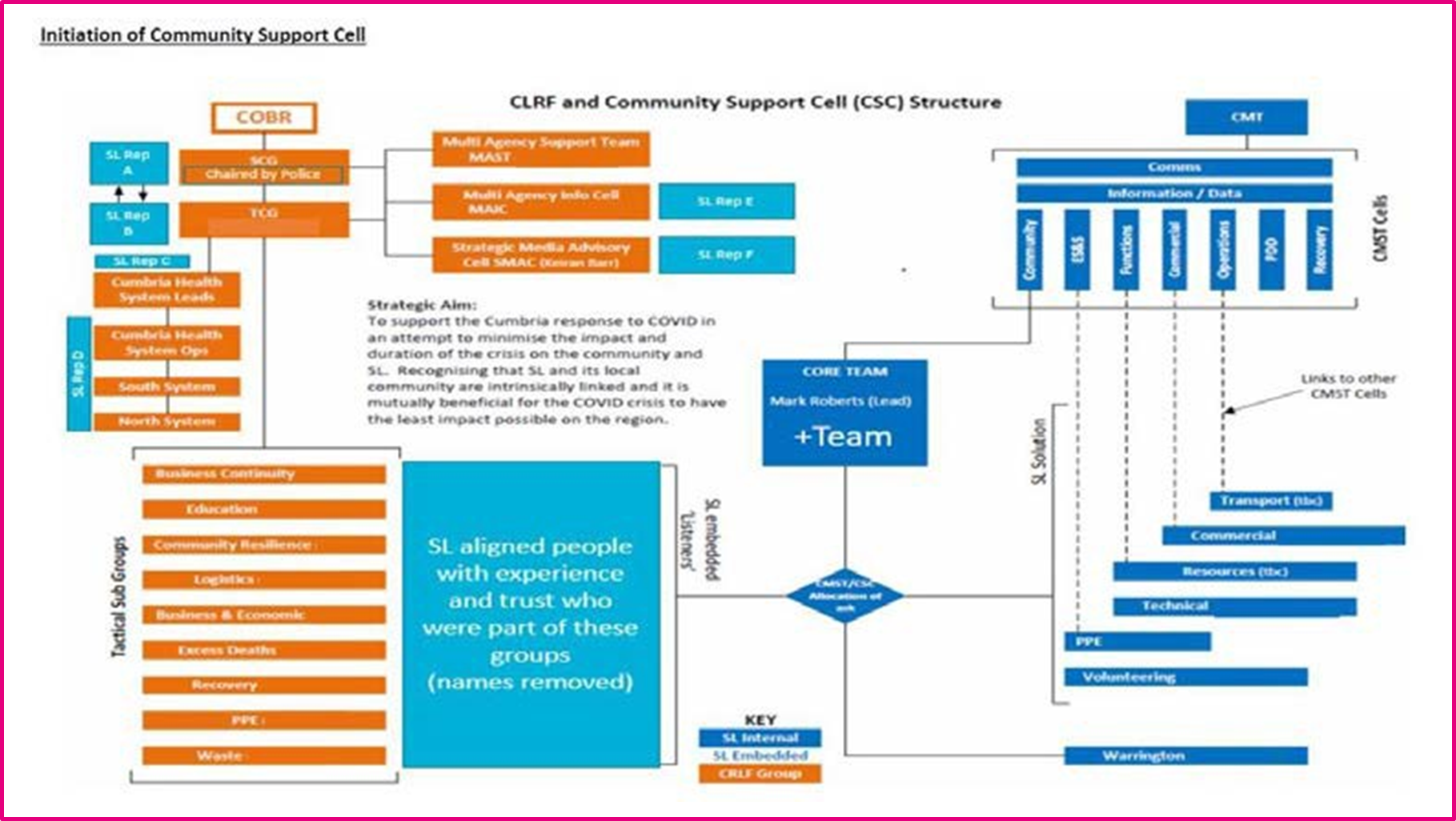

9. Sellafield Ltd and Cumbria LRF ‘Community Support Cell’ partnership response to Covid-19

The Covid-19 pandemic was the catalyst that influenced Sellafield Ltd (SL) to establish a Community Support Cell (CSC) in the Cumbria Local Resilience Forum as part of its crisis management arrangements. The CSC worked to directly place the project lead plus a team of four Sellafield employees on secondment in the LRF. Embedding the SL footprint and resources in Cumbria LRF enhanced the Covid-19 response in Cumbria, improved resilience in the surrounding areas and led to a significant improvement in situational awareness.

Case studies 10 to 14 were led by charity and voluntary sector organisations:

10. Salford Community and Voluntary Services (CVS): working together with Greater Manchester Combined Authorities to combat Covid-19

Salford CVS is the city-wide infrastructure organisation for the voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector. They run a Volunteer Centre which provides a volunteer brokerage infrastructure helping organisations to recruit, select, train and place volunteers into opportunities within the city and recruit, train and manage their own volunteers including Civil Contingencies Emergency Response Volunteers. Salford CVS successfully mobilised people to help provide a response to the 2015 flooding and Manchester Arena Bombing and their CEO recognised a need to make more formal arrangements to enable a VCSE and volunteering response to be better co-ordinated and effective.

11. Fermanagh Community Transport Ltd (Charity Registered Status) Northern Ireland

Funded by the Department of Infrastructure and the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs, Fermanagh Community Transport (FCT) has provided transport for the community since 2013. Prior to Covid-19 FCT offered a ‘door-to-door’ accessible and demand responsive transport service for those individuals and communities without access to public transport or a private vehicle. At the start of Covid-19 the service was modified to continue to support their vulnerable client base, as well as expanding their range of services to support all the community residents regardless of age, transporting Covid-19 resources as well as people and gathering intelligence on local needs.

12. Action for Children: Omagh & Fermanagh Family Support Hub Northern Ireland

Action for Children (AFC) is a UK-wide charitable trust. Established in 1861, it provides a statutory service that helps children and young people to thrive and overcome difficulties by providing a service in partnership with 512 local authorities across the UK. During Covid-19 AFC extended its provision of online emotional support and advice to children and families. They are also part of a network linked to business support that helped to provide food, children’s essentials, housing for homeless young people, educational resources, home repairs, home appliances, and technology support for home learning.

13. Spark Somerset: brokerage networks for community resilience

This innovative brokerage charity organisation has provided critical support for community resilience in Somerset during Covid-19 by supplying a source of volunteers, contributing towards a county network of resilience providers and supporting partnership working through an Integrated Volunteering Group that brings together organisations from across the statutory and voluntary sector. The project expands networks and partnership working through a local intelligence brokerage and digital platforms, whilst working in collaboration with the LRF, voluntary sector, volunteers, business enterprise and statutory bodies.

14. Voluntary and Community Sector Emergencies Partnership (VCSEP), Greater London and the South East

The Voluntary and Community Sector Emergencies Partnership (VCSEP) is supported by the British Red Cross which hosts the VSCEP by providing a range of support including IT, HR and Systems Support. VSCEP is a coalition of 250 national partnerships that work together in preparing for, responding to, and recovering and renewing from, disasters. Developed in response to the 2017 floods and the Grenfell Tower fire tragedy, the VSCEP offers a partnership approach by bringing local and national voluntary and community organisations together with emergency providers, so they can work together more effectively. The VSCEP case study shows how the Greater London and South East areas developed sustainable working relationships with hard to reach groups and accessed a range of resource networks that serviced impoverished areas in the regions during Covid-19.

Case study 15 was led by a new community group:

15. Blackwood and Kirkmuirhill Resilience Group, Scotland: New community group established for Covid-19

This community group was formed by a committee of six volunteers and over 30 volunteer responders who, together, have adopted a team working approach to community resilience. The main focus of the group at inception was to provide essential services to the most vulnerable in the community during Covid-19 isolation. This was achieved through three activities. First, service delivery was coordinated through a call centre. Second, community engagement and outreach activities were designed to promote both physical and mental well-being. Third, working with other organisations and partners promoted community recovery.

As can be seen by the descriptions, the case studies differ in design, but together

they demonstrate the ingenuity, commitment, and community spirit that abounded

during Covid-19 in support of our communities. In Part Two of this report you can

read all 15 case studies in full – written by the research team but with editorial control

resting with participants.¹

The research presented in this document was funded by the JRSST Charitable Trust in recognition of the importance of the issue. The facts presented and the views expressed in this report are, however, those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Trust.

Key Findings

The key findings of the research are structured into six factors that influenced the success of the initiatives.

1 | Leadership and Strategy

An overwhelming finding from all the case studies was that effective and agile leadership was a key enabler of their Covid-19 work. Examples of good leadership showcased in the case studies include:

- leaders pursued innovative growth and productivity by bringing together internal resources in new ways

- leaders worked in challenging conditions, e.g. moving online, working with imperfect information, and with a new speed of communication and co-ordination

- decision-making in new situations involving innovation and risk-taking

- new levels of trust had to be built to support making internal changes so the initiative could thrive in the new environment

- autonomy to make decisions was cascaded downwards to develop and operationalise strategy and plans quickly

- new intergroup working was evident to pool resources to succeed

- agile working meant local information on the locations of needs could be gathered and offers of support managed

- strong communication ensured co-ordinated action was as efficient and effective as possible.

Interviewees consistently referred to their activities as being ‘entreprenerial’ in character, and meant working differently within their organisation, helped by the context of normal working practices being in enforced flux. The concept of ‘intrapreneurial leadership’ (Cadar and Badulescu, 2015), explains the Covid 19 project leaders ‘entrepreneurial’ endeavour in a paid employee capacity. This differentiates the research participants from the term ‘entrepreneurial’ which generally applies to self-employed business ventures. Unexpectedly, the urgent demands of the pandemic encouraged local government to allow Covid-19 project leaders to innovate with their teams and apply an intrapreneurial leadership approach to ensure services were responsive to the changing conditions. For example, leaders were given autonomy and were responsible for designing project capability, resource acquisition, encouraging agility, and mitigating risk whilst building trust as they innovated.

Intrapreneurial leadership is the leadership of Intrapreneurial activity inside a place of work (Antoncic and Hisrich, 2001) and one benefit of this approach was that the dedication of senior staff was visible to volunteers, evident through a series of new activities to support them, such as risk assessment to ensure volunteer and beneficiary safety, acquiring resources such as personal protective equipment, and providing online training to volunteers. This commitment was enhanced by gaining the trust of volunteers which supported the retention of those volunteers who were essential to the success of the projects. The design of initiatives was not static and evolved as the pandemic unfolded, partnerships matured. When different types of need emerged from Covid-19 in the second year the volunteer profile changed to include many people who had been furloughed and were now affiliated to established organisations, which helped to maintain volunteer motivation.

Leaders from charities and voluntary groups also displayed intrapreneurial traits but were less enabled by their organisations than were those working in local government. This was especially true of those charities with national headquarters that had infrastructure and strict procedures in place which meant they had less autonomy. Newly-formed community groups and local government were agile in allowing intrapreneurial leadership to flourish.

As well as working effectively internally, leaders also had to work with partners outside of their organisations and applied the relevant leadership skills to make collaboration work. For example, they had to:

- develop strong working relationships with partners to understand emerging needs and know who else was working in the space

- develop trust in the working relationships to enable a focus on delivery

- accept and manage risk when working with others in the design and delivery of innovative services that had not before been delivered in their shape and scale

- manage the influx of new external intelligence which added a richer depth of understanding to their internal system

- exercise ‘informal situational trust’ (Liao et al, 2010) towards partners which included ‘emotional labour’ (Brotheridge, 2006) to motivate, and show sensitive awareness to volunteers acknowledging the value they placed on collaboration, e.g. through the use of appropriate language to work closely as equals

- maintain partner motivation

- adapt system and process designs in an agile manner for their innovations.

Emphasis was put on the need to build trust with partners to co-produce activities – both placing trust in the partner and being trusted by the partner. This combination of mobilising internal resources and maximising external relationships enabled all case studies to work towards scaling their activities to address the new demands brought by the pandemic.

Ten of the 15 case studies designed their initiatives without national direction and, while all worked with local business, most recognised there was considerable scope to expand ways of engaging with big business and the role of corporates in societal resilience.

2 | Partnerships

The 15 initiatives involved different combinations of partnership working, spanning collaborations with Local Resilience Forums (LRFs), local government, statutory agencies, volunteers, national and local charities, community organisations, and local small and large businesses.

Working with individual volunteers seemed successful across all case studies. LRFs used online systems and social media to attract and recruit new volunteers at speed – engaging in this way with mutual aid groups and spontaneous volunteers. An important aspect of working effectively with individual volunteers was project leaders organising online and face-to-face meetings to brief volunteers, making sure to use language that was accessible to all. Such briefings (and their associated working instructions) focused on volunteers working safely with beneficiaries, many of whom were in the shielding population or were self-isolating with Covid-19. This relied on softer management skills when working with volunteers – a type of ‘informal situational trust’ (Liao et al, 2010). The aim to achieve inclusivity across the community by recruiting a wide range of volunteers to deliver activities during Covid-19 is a critical feature of success because it supports trust in democracy, without which community resilience would have been undermined.

Much work was done in partnership with charities and voluntary sector organisations. This involved some charities changing their recruitment systems to recruit online so they could surge at pace to address unprecedented levels of demand. National charities exploited existing long-term partnerships and relationships with business and those partnerships allowed them to draw in large volumes of resources. Charities that had previous experience of working with corporate businesses had an infrastructure and approach to such collaborations that served them well in during Covid-19.

All except one of the initiatives worked with local businesses to deliver value – particularly with pharmacies and food-related business in the first year, and more poverty-related resources in the second year. Local governments established strong working relationships with local businesses but this was a relatively new venture requiring perseverance and nurturing throughout Covid-19. Managing business partnerships was a new feature for some of the initiatives and so the development of these networks was on a continuum of growth. One opportunity that was evident in the case studies was the potential for local government to develop wider and deeper working relationships with corporate partners and local business given the change in context and shared aims and objectives. There is learning from national charities on how to achieve this long term aim and add value to the sustainability of community resilience.

Collaborations with other parts of local government that were not normally intertwined with resilience blossomed during Covid-19 and was a cornerstone of many of the local government-led initiatives. For example, partnerships with statutory authorities, particularly with health and social care, were built into the Covid-19 systems so they could be actioned at speed, at scale, and for prolonged periods.

3 | Co-ordination and communication strategies

A key communication feature of the Covid-19 projects was exploiting different social media platforms for community resilience and, in some cases, to coordinate needs and offers of support. All of the leaders welcomed a rapid shift towards introducing online communication systems given the distributed nature of leaders, staff, volunteers, and beneficiaries. These systems were also essential to creating agile ways to rapidly coordinate activity in the challenging landscape of Covid-19. This included developing systems that could gather and share information and intelligence at speed, between leaders, staff, volunteers, and beneficiaries.

Systems had to constantly evolve and mature as they were implemented, accommodating the different types of need that emerged during Covid-19 as the situation and restrictions changed. This evolution involved:

- The creation of new and advanced functions to respond to the changing strategy for their initiative

- Understanding, assessing, and responding to changing risks which required fast communication to ensure safety of delivery

- Online systems to provide an ongoing dialogue of communication and co- ordination with all partners, including volunteers, statutory services and local business partners

- Adapting online systems such as updating websites, providing hybrid access to resources (e.g. helplines and printed leaflets) for hard-to-reach groups in different languages, and supporting citizens who had no access to technology

- Adapting systems to facilitate two-way communication and to gain intelligence, with these eventually being monitored over a 24/7 period

- Communicating the need for resources at speed which demanded rapid communication and co-ordination

- Recruiting local businesses and organisations to register donations of goods, money and other resources

- Adapting face-to-face training for volunteers to online delivery accessible through websites

- National charities implementing secure online communication and co- ordination systems at the local level

- Effective co-ordination and communication systems enhancing access to local intelligence and information about Covid-19 from national systems

Coordination and communication was central to successful delivery of community resilience. For example, the case studies show difference between creating a balance between autonomy, safety, and control that did not stifle volunteers’ initiative and helped to build trust with local communities. This was important to keep volunteers motivated and feeling valued. Businesses worked most effectively with the local arms of national charities – the collaboration benefitting from national infrastructure which enabled access to a huge range of business donations and services. Co-ordination with national charities for the vaccine rollouts did not work so well initially, however the transport organised by volunteers for vaccine appointments worked very well. Whilst they were offered affiliated charity volunteers to help with the task, some local governments found the co-ordination was not as fast and effective as working with their own volunteers.

4 | Local intelligence

Local intelligence and information management was vital to the success of Covid-19 response. Volunteer feedback was a key resource for gaining on-the-ground intelligence across the localities. Volunteers and mutual aid groups provided knowledge and intelligence about changing needs of vulnerable people who were shielding or hard-to-reach. Information and intelligence flowed from the ground up and was responded to quickly according to the design of the initiative. The information was used by wider partners that could respond to needs, for example with shielding systems and the use of face masks. Local intelligence also helped leaders to:

- Understand local concerns about Covid-19 vaccines which helped organisations to design information to meet communities’ needs such as providing different communities with information in their languages

- Highlight needs of lonely and vulnerable people who were shielding and experiencing other problems – by volunteers using feedback systems to provide such information into the initiative which was then passed to the relevant authorities

- Understand the changing needs of local communities, g. from the need for food and culturally-specific or health-related food in the early stages of Covid-19 to the emerging need for financial advice and essential items in the face of poverty later in the pandemic

- Advise beneficiaries on how to access the help that was available, g. support on housing, mental health, poverty

- Respond quickly and pinpoint those most in need by feeding knowledge from requests into partner systems, so building a bigger picture.

The ability of the initiatives to accumulate information on needs highlights the trust that was built between vulnerable people, voluntary organisations, and volunteers. Building information and intelligence from communities about poverty shed light on the shift between the early phase of Covid-19 (when the focus was on older people shielding and the need for vaccine support and food/pharmacy deliveries) to the transitioning needs towards poverty and economic loss in the later phases.

5 | Management systems

It was clear from the interviews with leaders that management systems were designed to ensure volunteer safety, effective partnership working, and agility in the Covid-19 delivery – all of which contributed to being able to manage a dynamic range of activities in an ever-changing environment. Trust and risk management were key features of the management systems, as was working to a needs assessment from local government. There were commonalities in how the initiatives managed their systems, as well as differences.

The greatest management commonality across all of projects was how they incorporated the traits of an intrapreneurial leadership approach, as discussed earlier. That came with challenges as well as benefits – there was a tendency for the leaders to work excessive hours to ensure the initiative was managed effectively, and for some that meant their continuous commitment as managers. Other commonalities include:

- Managing people and operations online

- Managing the safety of volunteers and In addition to training, this included security checks, providing PPE and insurance, visible lanyards, identity documents to show affiliation and legitimacy, following GDPR requirements

- In some cases, management came more through co-production by teams working together in locations or on problems

- Relying on people with whom they had previously worked with and built mutual trust

- Most leaders being sensitive to the emotional needs and capability of the volunteers, however, a minority of volunteers reported being ‘burnt out’ as the pandemic progressed

- Managing spontaneous volunteers, mutual aid groups and community action groups into their delivery roles.

One significant management function difference was the provision of training for volunteers which ranged extensively from a command-and-control type of training through to a lighter touch safety training. Some initiatives obtained financial grants from external sources, such as NESTA, which they used for Covid-19 delivery but this was patchy. Those receiving funding sought to act with long term sustainability in mind – using that money for start-up costs and not ‘baking in’ additional systems costs which would require ongoing funding support.

6 | Delivery of response

All except one of the Covid-19 projects were delivered by volunteers who provided the main delivery arm for community resilience resources – the exception being Sellafield Ltd, where paid staff were seconded to support the initiative but also gave time beyond paid working hours. The team leader seconded to the LRF reported that the commitment to the task was 24/7. The capability to deliver community resilience was strengthened greatly with the input of a national businesses able, for example to offer Sellafield volunteers in rolling shifts, as well as other Sellafield employees who volunteered outside working hours.

In the first phase of Covid-19, the delivery focus was predominantly on providing food, health resources and services to the elderly, those who were shielding or those who were self-isolating, as well as managing the transport issue for the roll-out of vaccines and support in the vaccine centres. In the second phase, the focus broadened to support families and hard-to-reach groups who were experiencing poverty and had complex additional needs, made worse or more difficult to manage during the pandemic.

To varying extents, all of the initiatives benefitted from involvement and support of local government, individual volunteers, community groups, charities and voluntary organisations, local businesses, and other partners. Seldom were initiatives able to function without the support of the volunteer delivery arm and a wider range of supporters or collaborators.

Some of the services that initiatives delivered are:

- collection and delivery of prescriptions, medications, and PPE

- counselling and visits to help older people shielding, children, families, and youth

- support, events and clubs for the lonely and shielding to help them back into society

- food acquisition, kitchens, delivery, and working with food banks

- vaccine transport and support at vaccine centres

- providing information about Covid-19 to hard-to-reach groups and to address vaccine hesitancy

- transport for older people, or those with health issues, to visit shops, for health and social care

- transport for the deceased

- transport and housing the homeless and youngsters up to 19 years old (to prevent youth homelessness)

- acquisition and transport of essential furniture, white goods, clothes, and baby resources

- money grants for electricity and heating

- providing a baby crèche and children’s Christmas parties

- providing storage facilities

Summary

In each case study in Part Two you will read about the important steps forward made possible by the efforts of a group of motivated individuals working together. These steps are a testament to the intrapreneurial spirit of leaders, partnership working, and how leaders motivated, trained, valued and retained volunteers to form the backbone of the delivery arm for future societal resilience. To highlight four such examples:

1. a community action group (Lincolnshire: Branston Parish Community Action Group) is now registered as a charity and is running its own food bank

2. a new community volunteer group (Blackwood and Kirkmuirhill Resilience Group) has developed a strategic plan for grassroots resilience

3. organisations have increased social media use for the recruitment and retention of volunteer

4. new skills have been acquired in terms of partnership working and leveraging partner relationships to acquire resources and grants

This study has found how the combination of state and civil society organisations working together has delivered initiatives with startling impact. The case studies collectively demonstrate that, once formed, new groups and networks can quickly evolve and then continue to function, enhancing resilience. However, working with partners at short notice, at speed, and without the luxury of supporting processes and structures can be challenging – it involves building trust, team working, developing and maintaining working relationships where all voices count, combining approaches, and pooling resources. Covid-19 has provided valuable lessons, and there is potentially more that resilience partnerships can do to share good practice – for example on gaining resources for community resilience from big businesses.

The focus on volunteer safety and training helped to minimise risk to themselves and to the communities they were supporting. This will undoubtedly be a topic of further consideration, building on the invaluable experience built during the long duration challenge arising from Covid-19.

We commend the case studies to you and celebrate the accomplishments of all those involved in their design and delivery.

References and Resources

¹ The research process to develop the case studies involved the principles of engaged scholarship (Van de Ven, 2007). Case studies were developed from semi-structured interviews which aimed for ‘dialogical sensemaking’ (Cunliffe and

Scaratti, 2017) to capture the lived experience of interviewees – this sense making process explored the meaning, relevance, impact, temporality, and performativity of activities (Macintosh et al, 2017). Secondary data (e.g. documents, websites) was also used to prepare for and contextualise the case study interviews.

Antoncic, B. and Hisrich, R.D., 2001. Intrapreneurship: Construct refinement and cross-cultural validation. Journal of business venturing, 16(5), pp.495-527.

Brotheridge, C.M., 2006. The role of emotional intelligence and other individual difference variables in predicting emotional labor relative to situational demands. Psicothema, 18, pp.139-144.

Cadar, O. and Badulescu, D., 2015. Entrepreneur, entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship. A literature review. (2015): 658-664.

Deakin, N., 2001. In search of civil society. Macmillan International Higher Education

Liao, Q., Cowling, B., Lam, W.T., Ng, M.W. and Fielding, R., 2010. Situational awareness and health protective responses to pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. PLoS one, 5(10), p.e13350.

The Case Study Initiatives

Case Study 1

Somerset Local Authorities: Vulnerable People and Community Resilience (VPCR)

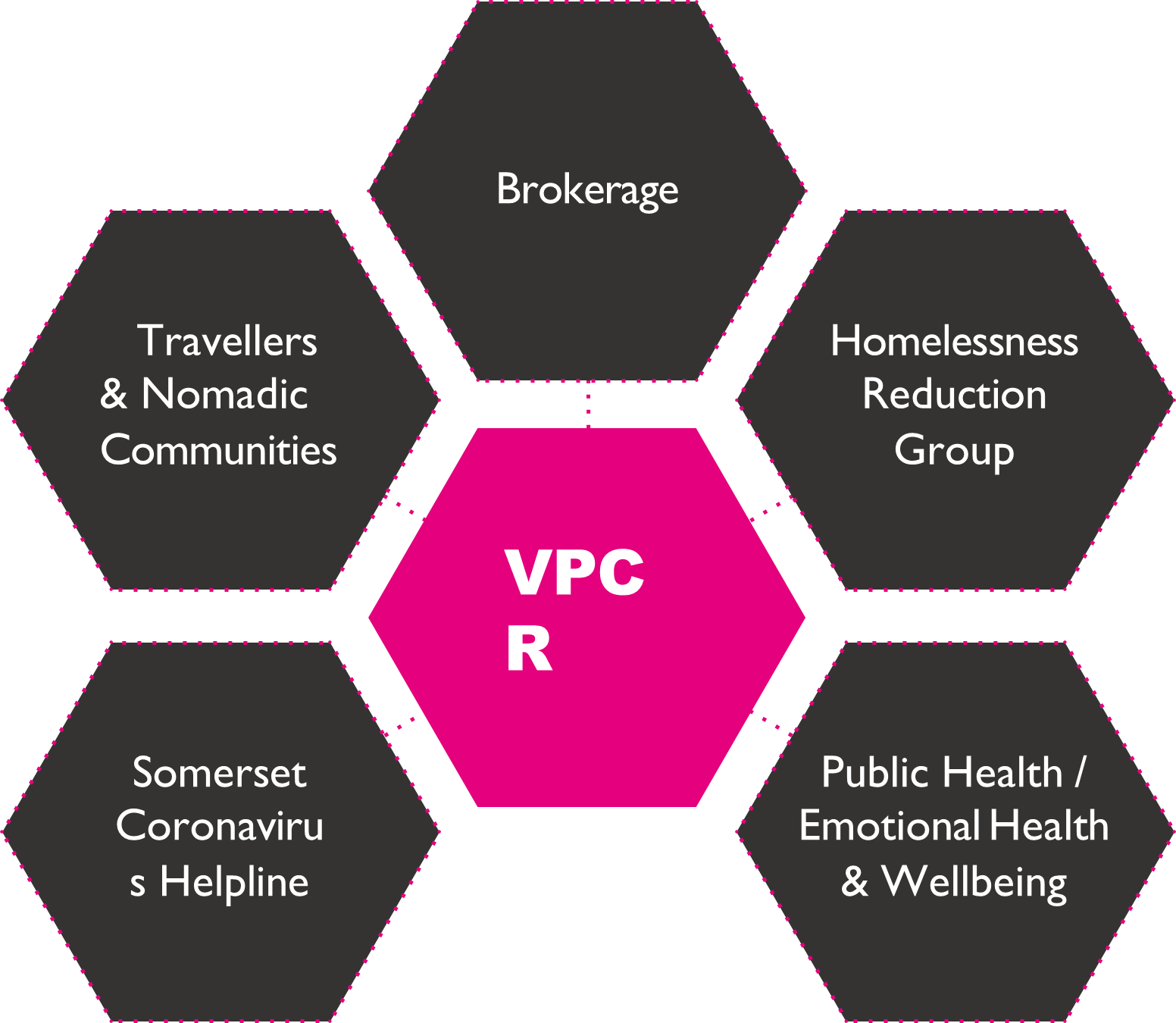

Alyn Jones, Director of Economic and Community Infrastructure Operations, Somerset County Council, explains the rationale, design and impact of the Somerset Local Authorities Vulnerable People and Community Resilience (VPCR) project. This innovative Covid-19 Community Resilience project recognised the need to respond rapidly to support the needs of vulnerable people in Somerset. The multi-agency initiative quickly established itself by involving volunteer delivery partners, which helped to connect the right people and organisations to the right local people, as well as implementing a centralised system of communications and information. The project expands networks through known contacts, digital innovation, brokerage and a one-stop shop. By working in collaboration across sectors, which involves volunteers who deliver the service, it has contributed towards a county network of resilience providers with a particular focus on health, wellbeing and food support for the most vulnerable.

Working Together: Developing Networks for Community Resilience through a Strength Based Approach

Project Design

“We were consultative and collaborative and when it didn’t work we still got on with it. By working together, that was the power of the VPCR cell by keeping all of those agencies working together”

The original aim of the VPCR cell was to develop a system that rapidly targeted at-risk groups to support their health, safety and wellbeing during Covid-19. Alyn explains “we quickly realised we had to bring in all of the issues that weren’t particularly healthcare. We also realised that other vulnerable groups were not necessarily shielding, including the travelling community, nomadic communities, vulnerable families known to GPs, and others in need”. When shielding commenced “we did not have one way of working that brought all the agencies together, and the rationale was to connect all of the agencies. We started to think… why are we creating centralised delivery services? Can we connect the community sector and have a collective response for the delivery of food”?

That vision informed a strategy that “connected the community groups so that delivery was from the community and they could have the conversation about why they were struggling. This moved us away from a demands-based approach towards more of a strength-based conversation”.

Alyn describes his leadership as “allowing everyone a voice, so one of collaboration”. He also makes the point “It was ultimately about not being afraid to make the decision and implement it. I was allowed to make decisions at speed and the governance was really important because I knew exactly the rules within which we were working”. Notably decision-making parameters were established at the start of the project.

Project Capability

The VPCR formalised a solid infrastructure and within a week identified a food storage area that was previously an empty space. Food finance included £2.5 million funding invested in food delivery, community pantries and community fridges, which provided nutritional food across the range of need in the Somerset community. This included emergency food for children and families in need (e.g. through food vouchers, school meal clubs, food banks). Financial support from different funds was available for marginalised groups, families, and people in crisis as well as community organisations. In terms of the financial accountability the VPCR had a finance representative however, Alyn was responsible. To ensure that the finance was spent the right way Alyn introduced a viable systems approach.

A practical challenge was to bring everyone together in a two-tier authority, and involve the voluntary sector, as well as the community. Constant communication with the different stakeholders informed the infrastructure and the system “connected the strands, that was the power of the VPCR cell, we had all of those agencies together and the reach into the relevant community sector organisations”. Supported by the Senior Management Team and a very good project manager, Alyn’s role as chair enabled him to recruit “the right people representation from district council, input from the NHS, NHS Commissioners, Social Care, CCG Commissioners, and representative from the voluntary sector and community groups”. The representatives were voices and influencers in their own areas. For example, the people from the Homelessness Reduction Group had the respect of their peers and the politicians.

Figure 1. Sub-cells and groups represented at the VPCR cell1

Coretotheprogressionfromdemand-basedresponsetowardstrength-basedconversations was connecting the right volunteers and voluntary organisations with the corresponding needs of people. Most important was the task to get the right people from the voluntary sector to the door of those in need, so they could have the conversations about what was needed. More than 1,400 volunteers joined the VPCR project, many of whom delivered food, and met the VPCR aim of having “the right community connector turning up at the door, that is able to reach back into the relevant organisation”. The relationship between volunteers and those in need prompted conversations that gained insights into why people might be struggling or in need of support. Trust in the volunteers was evident as their feedback to the VPCR provided valuable information about what different individuals and groups of people needed in terms of support. Volunteers’ knowledge transfer enabled the VPCR’s understanding of support to evolve from one of a transactional nature to a more nuanced, strength-based and holistic approach.

VPCR members expressed concern at the low level of nutrition in food delivered by external suppliers to those in need. Access to some residual funding helped the VPCR group “to understand what they needed. As the National Government support slipped away, we needed to keep local communities supported – to start creating food pantries, supply chains and doing a risk-based assessment of all of the food banks and beginning to understand what they really need, not just turning up with a pallet of food”.

Information sharing worked at three levels:

- Establishing performance management information-sharing mechanisms, which involved data analysis to understand: how many people needed support and where are they located?: what have we done for them, and what is VPCR engagement like? Data collection focused on sensitive areas, including how to assess their food quality and the levels of vulnerability, and what their food banks are

- Development of a consistent policy of over-communication, followed by a ‘hot debrief’, was a strong feature of internal information sharing.

- Creating a digital and brokerage communication system with external parties, including the public, accelerated the growth of volunteers delivering the service.

The development of a one-stop shop with one phone number, and one email address enabled a quick and effective response for the public to engage with VPCR. The creation of a strong social media presence “provided another avenue for people to engage”. The use of online platforms helped different community groups to work together and allowed the VPCR cell to pull back from frontline delivery, transitioning into a more facilitative and supportive role. The public and the voluntary sector responded on Twitter and Facebook, and that “gave them the opportunity to praise the community” for the voluntary work they were undertaking. The establishment of a brokerage also enabled VPCR to identify issues, “such as the food supply group issue, and how we develop more sustainability”. Launched in April 2020 the helpline received in excess of 13,600 calls during Covid-19 and centre staff made 7,000+ welfare calls and assisted 50,000+ calls about vaccination appointments. The coordination of the project accelerated with the one-stop shop approach. Rapid response was a huge benefit “If you need to get help on the Covid-19 virus you phone one number now. We achieved that quickly and co-ordinating the delivery of food”.

Outcomes

Reflections on the VPCR include measuring the positive impacts in terms of the strategic aims, which in terms of performance management is a huge success. Alyn’s leadership style goes way beyond developing a viable systems model. Rather it shows the transformational aspect of leadership and innovation. Engaging the volunteer community for delivery, over- communicating internally and externally, introducing a one-stop shop, digital innovations and a brokerage, are features of the VPCR’s innovative success.

In terms of volunteer sustainability, the evidence of the tangible success also takes into account that some of the volunteers reported that they felt ‘burnt out’. To some extent the responsibility of volunteers’ wellbeing lies with their affiliated organisation, as well as the volunteers themselves. There is concern for volunteer wellbeing, which is a human resource issue that needs consideration for the future. Alyn raised questions about sustainability and concerns about the volunteers in relation to their burnout. Lessons learnt reflect these concerns and there was recognition that “we got it wrong on more than one occasion”.

In terms of the project sustainability there is acknowledgement and questions about how to “allow those community groups to work themselves and literally just step in to fix the odd problem or connect those groups …that’s how we measure our success”. Regarding community sustainability there are unanswered questions concerning “how sustainable are the measures we put in place, what are our current risks and how do we develop more sustainable solutions?”

The VPRC has recently changed to form the Community Resilience Partnership Group. The new group has adopted the terms and references of the VPRC. Currently the food strategy group meets weekly to ensure supply of food is available. Alyn remains involved in this group.

Case Study 2

The integrated strategic Design of bedfordshire local Emergency volunteers executive committee (blevec) and community emergency response teams (cert)

Mark Conway, Emergency Planning Manager, Central Bedfordshire Council, is the architect of Bedfordshire Local Emergency Volunteers Executive Committee (BLEVEC) and Community Emergency Response Teams (CERT). Together they form the interconnected strategic and operational parts of a community resilience volunteer initiative in Bedfordshire. BLEVEC volunteer Commanders work at the strategic level of decision-making and communicate effectively in a two-way system with CERT emergency volunteers, who provide support to the emergency services at the operational level in their local communities.

During Covid-19, BLEVEC and CERT responded rapidly to send volunteers to help with a range of tasks. The recruitment of volunteers is aligned to their partner network, which includes 55 organisations, 10 emergency faith providers, and 41 independent volunteers. By integrating the strategic and operational capabilities this design provides a 24/7 networked response which enables CERT volunteers, who are monitored by BLEVEC, to support emergency planners and emergency services across Bedfordshire towns and villages.

Background

“Anyone can apply to be a BLEVEC Commander, for example CERT members and voluntary organisation members”

BLEVEC is a sub-group of the Bedfordshire Emergency Volunteers Partnership, established in the 1970s. It is an Executive Committee led by a team of strategic decision makers comprised of highly skilled local volunteers known as Strategic, Tactical and Operational Commanders. BLEVEC Commanders work closely with emergency providers to ensure that CERT volunteers are placed in roles that utilise their valuable capabilities when working with the emergency services during a crisis. The Executive Committee meets two or three times a year to review critical incidents, policy and organisational issues. BLEVEC Duty Officers have their own WhatsApp group, which enables the immediate transfer link of intelligence, videos, pictures, and messages between the emergency ground site and the Emergency Planning Team. One message from BLEVEC can reach the whole network within minutes and communicate intelligence across the local areas. This intelligence can inform health and safety, as well as conducting risk assessment for volunteers so they aware of how their own capabilities can support the emergency services in a crisis. BLEVEC Duty Officers are also able to identify the appropriate volunteers to support the needs of the emergency services.

The BLEVEC structure includes:

- BLEVEC Commanders, currently 34 highly skilled trained and equipped volunteers, some of whom are retired include emergency planners, police and business BLEVEC Commanders include:

- Strategic Commander (Mark Conway) who represents the BLEVEC partnership and all members at the Strategic Co-ordinating Group (SCG) as well as the Recovery Co-ordinating Group (RCG)

- Tactical Commanders who represent the BLEVEC partnership and all members on the Tactical Co-ordinating Group (TCG)

- Operational Commanders who represent the BLEVEC partnership and all members at the Forward Control Point (FCP) at the scene of an emergency or a specific operational They will assess the situation, identify where volunteers resources might be useful, and manage requests from the emergency services for volunteers. They are visible by their Uniform, ID Card, JESIP Commander Card and PPE Grab Bag

- BLEVEC Duty Officers are mainly recruited from the Commanders and provide a mini control room for They have developed a WhatsApp group to provide intelligence across different areas during a crisis. A 24/7 emergency contact number enables immediate access to voluntary support for emergency services. This involves:

- Fielding requests for assistance and callouts.

- Decision making for the delivery of tasks.

- Identifying the appropriate person for the task.

- Activating deployment to emergency sites.

“Anyone who wants to volunteer and help their community in an emergency can join as an emergency response volunteer”

CERT includes over 27 teams comprised of volunteers who are coordinated by BLEVEC to support emergency services in their towns and villages when needed. Most of the teams include Town or Parish Council. CERT volunteers are recruited from the 55 member organisations in the BLEVEC partnership and community groups. The public at large are recruited through online advertising. Local CERTs provide invaluable local intelligence during an emergency and learn how to co-develop community emergency plans for their local areas through CERT mandatory training. They can also undertake additional training which provides an opportunity for CERT volunteers and public volunteers to join BLEVEC.

CERT volunteers are given identification cards and visible CERT clothing so residents can identify who they are. Equipment is provided for various types of risk that volunteers are able to undertake. The CERT Emergency WhatsApp group provides immediate intelligence to Emergency Planning Teams. For example, CERT volunteers send information through messages, videos, and pictures from the site of an emergency to the Emergency Planning Team so they can plan an immediate response before arriving at the scene. CERT also have representation on the Bedfordshire WhatsApp Emergency Group which has 138 members who participate in the Local Emergency Volunteers Executive Committee. The Group is comprised of 55 member organisations and meets with the BLEVEC Commanders two or three times a year to review critical incidents, policy and organisational issues.

Project Design

The rationale underpinning the integrated work of BLEVEC and CERT is to operationalise an inclusive partnership approach to recruiting, training and maintaining a diverse network of volunteers from their partner organisations and the public at large. BLEVEC Commanders and CERT volunteers work together effectively in a networked strategic and operational structure with emergency services to make this partnership organisationally resilient and capable of meeting the needs of local communities during crisis. The vision incorporates an open door approach to recruiting BLEVEC Commander volunteers and CERT volunteers. The capability matrix structure ensures that all volunteers are clear about their roles and responsibilities. Both BLEVEC and CERT volunteers have been trained to communicate intelligence from the local and strategic level through their WhatsApp to the emergency services and engage together through 24/7 communication.

In terms of leadership, Mark Conway, Strategic Commander of BLEVEC and CERT has applied an entrepreneurial leadership approach towards establishing and sustaining a capability matrix system. The system links the strategic decision making to the local operational level in a three-way communication process, which includes BLEVEC, CERT and emergency planners and services. The design has embraced diversity and inclusion by accepting all volunteers who apply and agree to the mandatory training for CERT. Currently Mark works with 10 emergency faith advisors and is working to increase the recruitment of volunteers from hard-to-reach groups. The project design ensures CERTs work as effectively as possible with the emergency services, and this is monitored by the BLEVEC Duty Officers who allocate the volunteering tasks to align with the volunteers’ unique capabilities. The design incorporates a type of safety net for the agile volunteer network. The design shows the innovative side of his leadership which has enhanced community resilience in Bedfordshire both prior to, and during Covid-19.

Project Capability during Covid-19

Since Covid-19 lockdown this matrix model of community resilience has been applied to local communities’ needs related to the pandemic and has provided support to the most vulnerable in the community. BLEVEC/CERT Covid-19 response includes a coordinated response to mass surge testing, food deliveries, PPE deliveries and assistance in the set-up and management of test sites, vaccination sites, and management of the Kents Hill Isolation Centre, which helped Milton Keynes. The most common joint activity was establishing and running emergency assistance centres. Commanders adapted to chairing statutory and voluntary COVID cells across the region, including the Chair of the Voluntary Sector COVID Cell. Working together with national and local organisations enhanced response. Partner organisations include: Age UK, Citizens Advice Bureau, British Red Cross, AMYA Muslin Youth Centre, Mind, Samaritans, CHUMS (Child Bereavement), Herts Boat and Rescue, WRVS, Bedfordshire Multi-Faiths Emergency Response Team, RSPCA, Salvation Army, St John Ambulance, and BHC 4X4 Response.

CERT identified assistance centres in their local areas. CERT also provide opportunity for community residents who are not affiliated members of any voluntary groups or organisations to become a CERT volunteer. The open invite to become an emergency response volunteer draws on a HR function, as it requires attending a mandatory training session, where volunteers are provided with a CERT t-shirt and ID card, recruitment information pack, and membership of the emergency CERT WhatsApp Group. In addition to mandatory training CERT offers a range of optional monthly on-going training schemes to enhance their volunteer skills and improve volunteer capacity building, if the volunteer chooses to do so. Voluntary training courses range from CERT promotion to a Commanders (Commanders Part one and Part two) to the Vulnerable People Training Exercise (Vulnerable Puffin).

Outcomes

The efficient coordinated response to the Covid-19 crisis was remarkable. Volunteering roles included the Commander level, specifically coordinating ongoing actions, or the CERT locality involving transporting people in 4×4 cars or helping at vaccine centres. All volunteers are valued for their contribution. Sustainability is evident in the new pop- up groups, such as the Leighton Linslade Helpers, who are joining BLEVEC with 100 volunteers, appointing a Commander and establishing a CERT.

A clear area of impact is the rapid response intelligence system, which enabled BLEVEC Duty Officers to identify the capability of the volunteers and the skills they had to support the emergency services. BLEVEC Duty Officers can provide information of CERT volunteer capabilities to the emergency services at speed. Furthermore, their knowledge of CERT volunteer skills, roles and capabilities enhances volunteer safety.

Reflections for the future include:

- To develop a wider business network to increase the numbers of private sector volunteers, which they have achieved with TUI, Easy Jet and local business.

- To improve the system so the high volume of volunteers who present from national organisations are linked to local communities, and do not get lost in the process.

- To build new relationships with infrastructure organisations funded by Local Resilience Forums.

- To develop a wider network of faith leaders who can provide advice, expertise and support to those in their communities who are affected by emergencies.

Bedfordshire Prepared website offers links to join BLEVEC as an emergency response volunteer: https://tinyurl.com/38dc2c25

For further information view: https://centralbedfordshire.box.com/s/ g37vso39w32t4988o7xcdh36pg5ef4pu

Case Study 3

Ready For Anything – North Yorkshire

Introduction

“We wanted to embrace volunteer support for major incidents in a way that no one had before”

Tim Townsend

North Yorkshire County Council’s motivation to develop ‘Ready for Anything’ volunteer community resilience project stems from the public’s goodwill to help in the 2015 Christmas floods. During widespread flooding in North Yorkshire, particularly in the City of York, the public and people in the city contacted North Yorkshire County Council (via Facebook and in person) to ask how they could help. Aware that they had no official system to work with spontaneous volunteers, emergency responders had to turn them down. Following the 2016 flood inquest, and in discussion with York CVS, the County Council agreed to design a project to incorporate official volunteers into their response system. Gaining funding for two years for a pilot study, the City of York took this concept forward. Business was included from the start with a focus on supporting each other during disruptive events. In 2018 the County Council won funding from the social resilience stream at NESTA to develop a system that involves both volunteers and society. The project design covered the whole of the North Yorkshire LRF area and a team of four was placed in the resilience and emergencies team in the County Council. The project is now administered by North Yorkshire Council and owned collectively by the North Yorkshire Local Resilience Forum.

https://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/ready-anything/

Project Design

The rationale of ‘Ready for Anything’ is to establish an official volunteer group who receive volunteer training and can be deployed by the emergency services for practical support at disruptive events. A key aspect of the strategy is the wide range of volunteer training that is available, including involvement with LRF silver and bronze officer training. Training is designed through a stratified approach to harness the wide range of volunteer skills. Ready for Anything (RFA) volunteers are offered upskilling training opportunities and courses are updated every year. RFA volunteers are given a handbook that details their involvement in the ‘Ready for Anything’ system and explains different types of training available including (optional) exercising. Information is available about how they can be deployed to work alongside the emergency services.

The long-term vision to make the project economically sustainable stems from the team’s awareness that funding would finish. This factor informed their strategy. Rather than purchasing a customised IT package for the project savings were made by using Excel spreadsheets and Gov Notify texting system, which are cost free. Volunteer registration involves completing a simple form on the local resilience forum website. Contacting RFA volunteers during an incident involves texting those in nearby areas from a recognised number that volunteers can save in their phone contacts list. Some of the funds went towards the RFA volunteer equipment, including lanyards and fluorescent tabards to show visibility as a RFA volunteer. A cost was involved hiring halls for training. Initially a requirement of the NESTA funding was a push to target more volunteers who are over 50 years old because they recognised they had more free time, however currently they welcome adult volunteers of all ages from diverse backgrounds. The introductory training session can be accessed online, which proved cost effective, however, more face-to-face interactive events are planned for a post Covid-19 future.

Leadership

“We are absolutely passionate about working with volunteers”

Tim Townsend

Described as a ‘hands on leadership’ there is leadership decision making at the operational level and strategic level. Working in a team of four, three members undertake a role similar to line manager leadership. They design and deliver the training sessions, provide regular information e-mails to the volunteers, register new volunteers and assess RFA volunteers’ capabilities. Embedded in the community and working closely with RFA volunteers the team are identified by the community as the leaders of ‘Ready for Anything’. If they need to raise strategic issues they report back to the senior manager in the LRF. If emotional support is required following an incident debrief there is a specialist team available who can deliver this service. Strategic leadership decision-making on the deployment of RFA volunteers to an incident is a joint decision of the multi-agencies. If there is more than one request for RFA volunteers during a large incident, the decision to deploy RFA will made through a multi-agency advisory teleconference or tactical coordination group meeting.

Project Capability

“It’s all about trying to build that community, we have a lot of regulars that come back. It’s easy to get volunteers, but it’s the retention of volunteers that is the hard thing”

Tim Townsend

The capability of the project relates to the RFA volunteers optional take-up of the training available following the introductory training, and the trainer’s assessment of their varying levels of skill acquisition. Working with more than 300 RFA volunteers the trainers are committed to upskilling and always ensure that varied training from a variety of LRF agencies is available. This ongoing work helps with the retention of the RFA volunteers. Training includes RFA volunteering learning roles that could be utilised at a national level and in their local communities. The trainers also invite guest speakers, such as the police from the counter-terrorism unit. Coordinators on the ground can be recruited from various agencies in the Local Resilience Forum, including Local Authorities or emergency services.

Consistent to the early stage of the project, intelligence is shared through texting and regular emails. RFA volunteers are covered by the North Yorkshire County Council, Employer and Public Liability Insurance. RFA volunteers who use their own vehicles are advised to check that they are covered by their own insurance for business use and understand that they do not receive expenses for mileage. Given the varied and grouped nature of their roles, RFA volunteers are not required to take a DBS check. The coordination of the RFA volunteers incorporates an HR role in terms of assessing their capabilities for the required roles, including them in the Council’s insurance, and providing de-briefing sessions after incidents.

MIRT (Major Incident Response Team) is a small team of highly trained specialist volunteers that RFA can work alongside with, and who have two main roles. They manage and organise rest centres that are set up for displaced people after a major incident. They are also trained to provide immediate and long-term emotional support to those who have been impacted by incidents. Their expertise was requested after the Grenfell Tower fire because they have national recognition.

Roles that volunteers can provide include:

- Provision of refreshments to evacuees and to the emergency services.

- Rest centre support to assist those who have been evacuated, which can include providing information and reassurance.

- Clean-up duties following an accident to help people.

- Logistical support which includes the movement of equipment, administrative support and sorting donations.

- Warning and informing to help provide information to the public by leaflet dropping and sometimes knocking doors to inform people of the support that is available to them.

- Transport provision to assist with the movement of donated goods and supplies to areas where they are needed.

- Good neighbour support to contact their neighbours before, during and after an incident so they can ask if there is anything they need, such as medication or shopping.

- Business prepared involves supporting business to have a plan for robust preparation that could help a business to continue to operate with minimal disruption.

- Search and rescue – In high profile cases where a hub is set up for rescue services, RFA can provide support for the running of the hub.

Covid-19

During Covid-19 training moved online with the use of Microsoft Teams, an aspect that reduced training costs but did not enhance the aim of interacting more with the volunteers. The team’s initial response to the Covid-19 pandemic focussed on the safety of the volunteers. Guidance was offered when deploying to an incident, including the use of PPE and social distancing. Volunteers were also informed that there was no obligation to help and that text communication would continue as normal. During this time RFA volunteers were deployed in roles that involved supporting the most vulnerable during the global pandemic, as well as providing practical support during incidents. Having registered RFA volunteers who could be available to them was of great assistance to the emergency response agencies after the decision was made that they could be deployed. On occasions ‘Ready for Anything’ was asked for twenty volunteers at speed, and that was a task that took more time.

Outcomes

- The system of RFA volunteer training works effectively for the local resilience forum agencies and has a safety measure in place for the deployment of RFA volunteers.

- The delivery training team is highly motivated and work consistently hard through a two-way ongoing dialogue to keep the RFA volunteers engaged.

- The team measures the impact of their training by providing a space for feedback in the session.

- Forms are sent out to RFA volunteers asking if there was anything they could do better which gives them time to reflect on the training content.

- Being embedded in the LRF helps their visibility, integration and sustainability.

- Having different LRF agencies who could supply coordinators on the ground e.g. local authorities and utilities such as Yorkshire Water, these were able to cover volunteers under their own volunteer liability insurance.

- One new area being looked at is how they can incorporate spontaneous volunteers through temporary registration forms and embrace community Currently Lincolnshire LRF is looking at Yorkshire’s model with a view to replicating it.

The scheme has been running for three years and is now an established part of the North Yorkshire Local Resilience Forum.

More details available from: www.emergencynorthyorks.gov.uk/readyforanything

Case Study 4

Community Resilience Programme ‘What If’ – You Can Make a Difference (West Sussex)

Introduction

Established as a grassroots project in 2011 following significant flooding, ‘What If’ is a thriving innovative volunteer programme in West Sussex County Council that supports community resilience and is indirectly linked to West Sussex Fire & Rescue Service. It aims to empower local communities to help themselves and the most vulnerable during disruptive emergency events, but also promotes a greater community cohesion and resilience in their day-to-day activities. Volunteer training is available to learn about preparedness, response and recovery. Starting initially as a multi-agency of three local authorities (East Sussex, West Sussex, Brighton & Hove), West Sussex Fire & Rescue Service and volunteer organisations within the Local Resilience Forum, the ‘What If’ Programme was created. This case study looks at the West Sussex model. With the specific aim of improving community resilience, leaders of the project asked questions: What do you need? What could have made it better? Their answers informed the design of a preparedness, response and recovery project that could signpost, inform, support, share knowledge and improve community resilience. The ongoing ten-year dialogue with their volunteer network has enabled a depth of understanding of their communities’ needs. They engage people by

listening. The structure they have developed includes community resilience groups, youth groups, health and wellbeing groups as well as business organisations across the region. In terms of resilience outcomes, it has shown that “for any disruptive event that would affect their ability to continue with their business as usual, they had something really positive and practical that they could build on”.

Project Design

The rationale to help local communities to help themselves incorporates a vision of inclusivity for all age ranges, community groups, business and sustainability. The strategy involves designing a community resilience system that empowers and prepares adults, youth, local communities, and business organisations, so they can mitigate some of the issues in advance, respond during and support recovery. This includes following events to minimise ‘the impacts they may well suffer‘. Working with the communities at the grass roots level and delivering training at times to suit them is a key principle of the strategy. ‘What If’ is about developing a culture – it does not require a large financial commitment. The investment comes through engagement with communities, a willingness to be flexible and enthusiasm to deliver the messages ‘What If’ provides. The ‘What If’ project is comprised of four components:

Localised Training Programmes/ Meetings for Community Resilience: Training is undertaken by two ‘What If’ leaders, mainly through local parishes across the region. Information includes community resilience preparedness, response and recovery. Volunteers can learn a range of skills for emergencies and operationalise this knowledge through their community networks as well as sharing information and being good neighbours. The training includes sign-posting to gain insight and understanding of risks and where to get help. It provides practical ‘myth busting’ guidance and references the Social Action, Responsibility and Heroism Act 2015 (The SARAH Act).

The Youth Element: The aim is that the young participants will be motivated to continue to engage with community resilience values, such as volunteering, into adulthood. Youth training falls under the umbrella of The Duke of Cornwall Awards. Under Covid-19 lockdown the ‘What If’ team used the Duke of Cornwall Award resources and facilitated the training remotely. Originally, the Duke of Cornwall training was for uniformed groups such as Scouts and Girl Guides. More recently, the Awards have opened up to any children or young people’s groups and follows the progressions of Key Stages one, two and three in the education system. It starts with enabling young people to gain an understanding of their own personal resilience and broadens to learning about family and community resilience as they get older. Currently the youngsters involved in the Duke of Cornwall Awards are also engaged with COP 26 issues and consider sustainability and environmental issues within the award programme.

Duke of Cornwall Community Safety Award https://www.cornwall.gov.uk/fire-and- rescue-service/keeping-safe/community-safety/community-safety-award/

Health and Wellbeing: ‘What If’ includes the introduction of health and wellbeing support as a feature of community resilience. The health initiative supports vulnerable people to navigate the wide range of organisations within the health sector Working on the premise of ’making every contact count’.

“This supports not only vulnerable members of our community, but everyone, and provides a wide range of guidance via a single point of contact.”

It promotes healthy living and lifestyles and provides support and guidance to minimize the impacts of extreme weather and advice for managing utility disruptions, by providing links to register with Priority Service Scheme operated by utility providers and promotion of healthy living and lifestyles.

Supporting Business and Business Continuity: ‘What If’ reaches out to local business to make them aware of how they can support them in terms of considering and adopting business continuity into their operations. ‘Business’ also includes local care and nursing homes. Initially the ‘What If’ team asked questions: Do you have a business continuity plan? What have you considered? Do you have alternative premises or shared resources that you could share with each other? As part of the Fire and Rescue Service schedule of business fire safety visits literature promoting business continuity is also distributed, providing links to the Resilience & Emergency Team. ‘What If’ provides practical advice about heavy snow, flooding situations or any event that could prevent them from operating – e.g. denial of access to premises, utility failures, supply chains, or any obstacle that could stop the local community and businesses being able to continue with their day-to-day activities. Engagement with local community resilience groups is encouraged as there is a mutual benefit to being able to return to business as usual at the earliest of opportunities for both businesses and their communities.

Leadership

“There are huge savings and advantages with the programme, so engagement is not purely financial .If you’ve met with people who have been in properties that have been flooded, it can be incredibly traumatizing for those people. They also fear for the next time and when they see a severe weather warning their anxiety levels go up. So it’s not just about money, it’s about keeping communities resilient”.

Chris Scott

‘What If’ involves a ‘participatory’ leadership approach that engenders trust in the people, community groups and business organisations they seek to serve. The visibility of the two ‘What If’ community resilience leaders, who listen to the communities to understand what preparedness they need for community resilience, has embedded this trust. The ‘What If’ leaders also work in the environment of a 24/7/365 cover for emergencies across the county as they link directly with the Fire Service and provide the coordination of multi-agency partners to significant events and major incidents. Sometimes identified in firefighter uniform the team has gained the respect of local communities by their ability to listen and act. The willingness to adapt training times to meet local community needs, such as evening training, has won respect in their leadership roles for community resilience, as well as being perceived as respected critical friends. “So it’s about being absolutely inclusive and to involve everybody and certainly as I say, going right down to those grassroots” (Chris Scott).

Project Capability

The project capability meets a strategic aim by providing community resilience preparedness, response and recovery training that helps people/volunteers to help themselves and vulnerable people. A key feature of the project capability involves how the training informs the practical support that is available through community resilience volunteers. Core training elements involve: first aid, personal safety, identifying and supporting the vulnerable, team leadership and community welfare as well as factual information on health and safety. Training thus far has included the provision of some basic safety equipment. Examples of how training impacts community resilience volunteers include:

- Trust in the ‘What If’ team that deliver the training and share their knowledge.

- Increased confidence and knowledge following training on how to prepare, respond and recover, which starts with an introduction to emergencies.

- Learning what can be achieved to help the practical needs of vulnerable groups.

- Gaining an understanding about health and safety and what volunteers can achieve within their own safety boundaries.