Resilience Reimagined: a Practical Guide for Organisations

About this report

Published on: March 30, 2021

Resilience has been pushed firmly toward the top of the agenda for boards and senior management teams of organisations of all types. How can resilience be developed? Who does it well, and what can we learn from them? These and other questions shaped in-depth interviews and focus groups with leaders from a wide range of sectors. The research identifies seven distinct future resilience practices, which combine to form a new model for resilience.

This report was commissioned jointly by NPC and Deloitte LLP. The research informing the report was prepared and conducted by Cranfield University. The PDF download provides additional formatting and visual layout.

Authors

Professor David Denyer, Cranfield University

Mike Sutliff, Cranfield University

Executive summary

Resilience has been pushed firmly toward the top of the agenda for boards and senior management teams of organisations of all types. But how can resilience be developed? Who does it well, and what can we learn from them? What are the practical steps necessary to strengthen resilience for long-term success? As a leader, what more could you do to develop resilience for your organisation?

To address these questions, we conducted in-depth interviews and four focus groups with leaders (boards, senior executives,

policymakers and resilience directors) from a wide range of sectors.

Our research identifies seven future resilience practices. These will create a new model for resilience, which is set out in the report on page 41.

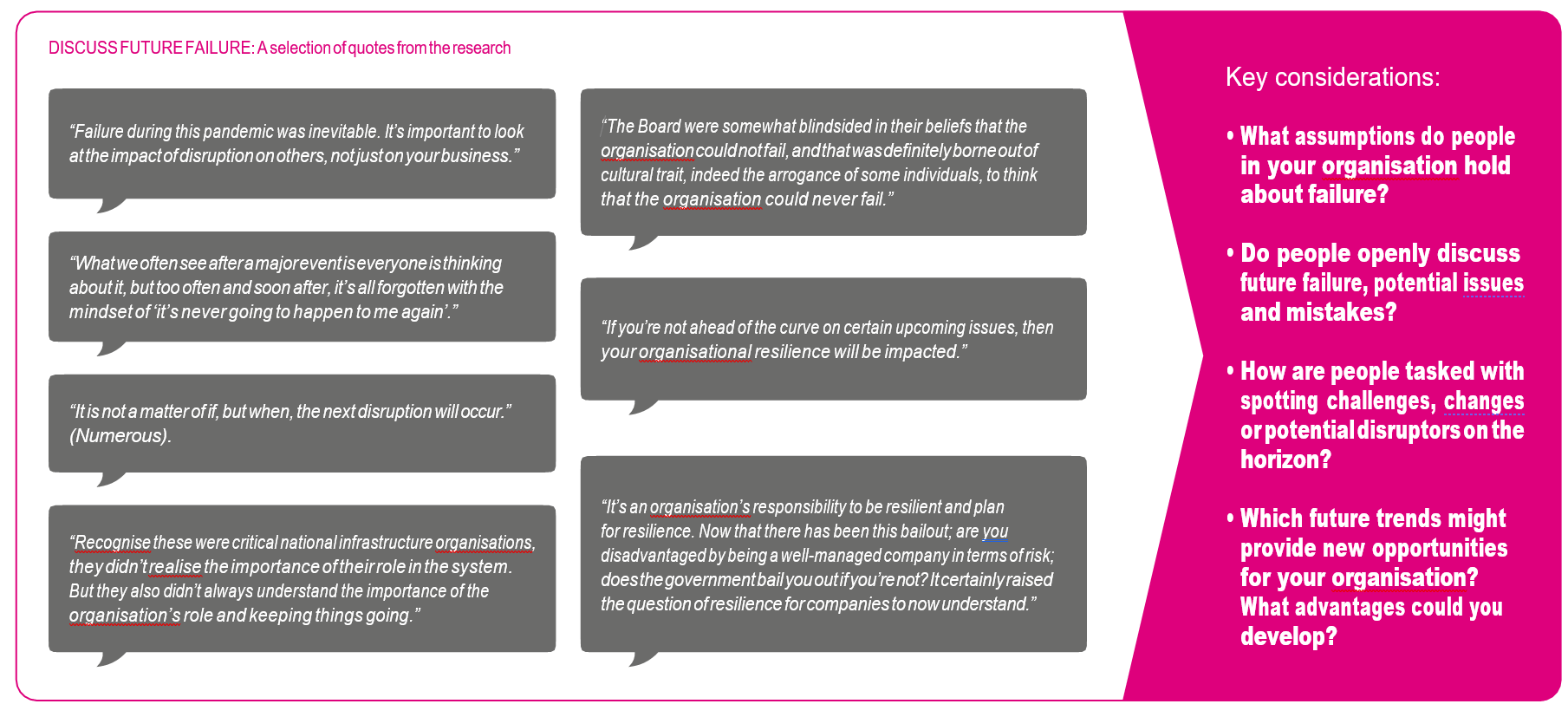

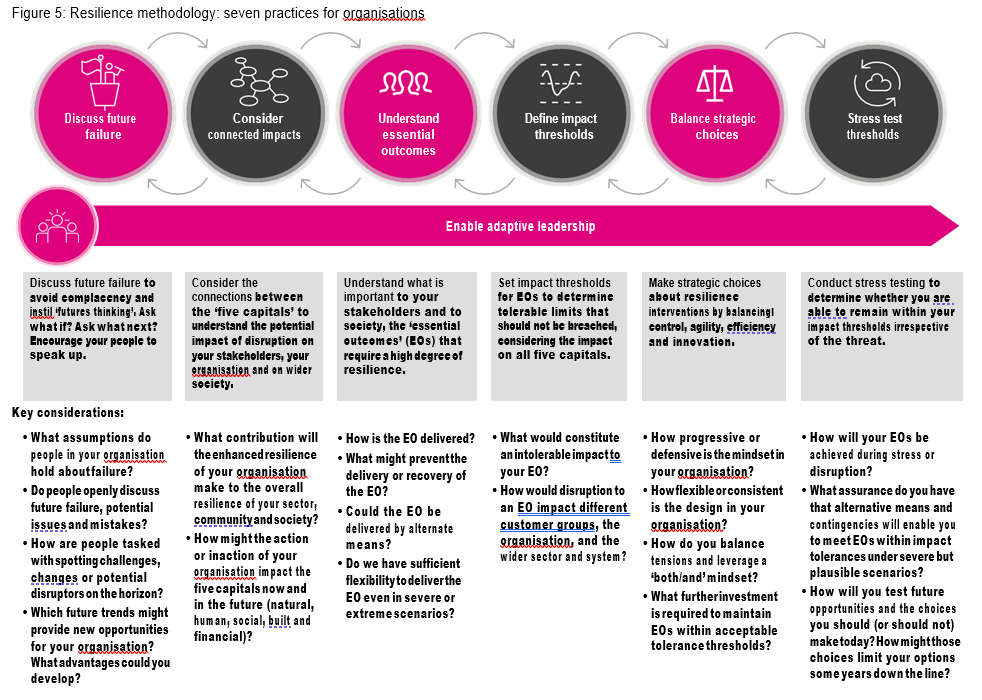

1. Discuss future failure

Discussing future failure will ensure a more positive outcome. Complex and severe events are often a failure of imagination. Resilient organisations accept that their designs, plans and operations are fallible – they ask what if? They also anticipate and make less complacent assumptions about future issues – they ask what next? They actively encourage people to speak up. We need to reimagine resilience as we enter a new period of uncertainty and change with an ever-increasing possibility of crises. Futures thinking and foresight tools are employed by government and organisations to give a perspective on longer-term opportunities and possibilities. They can inform specific choices we should (or should not) make today, particularly those that might limit our options some years down the line.

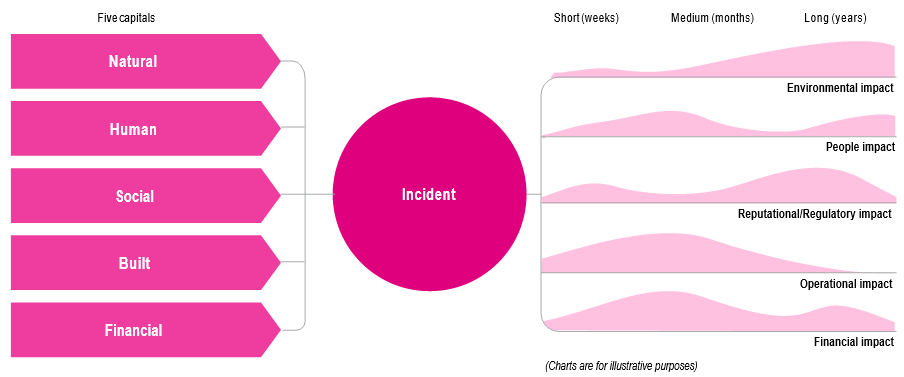

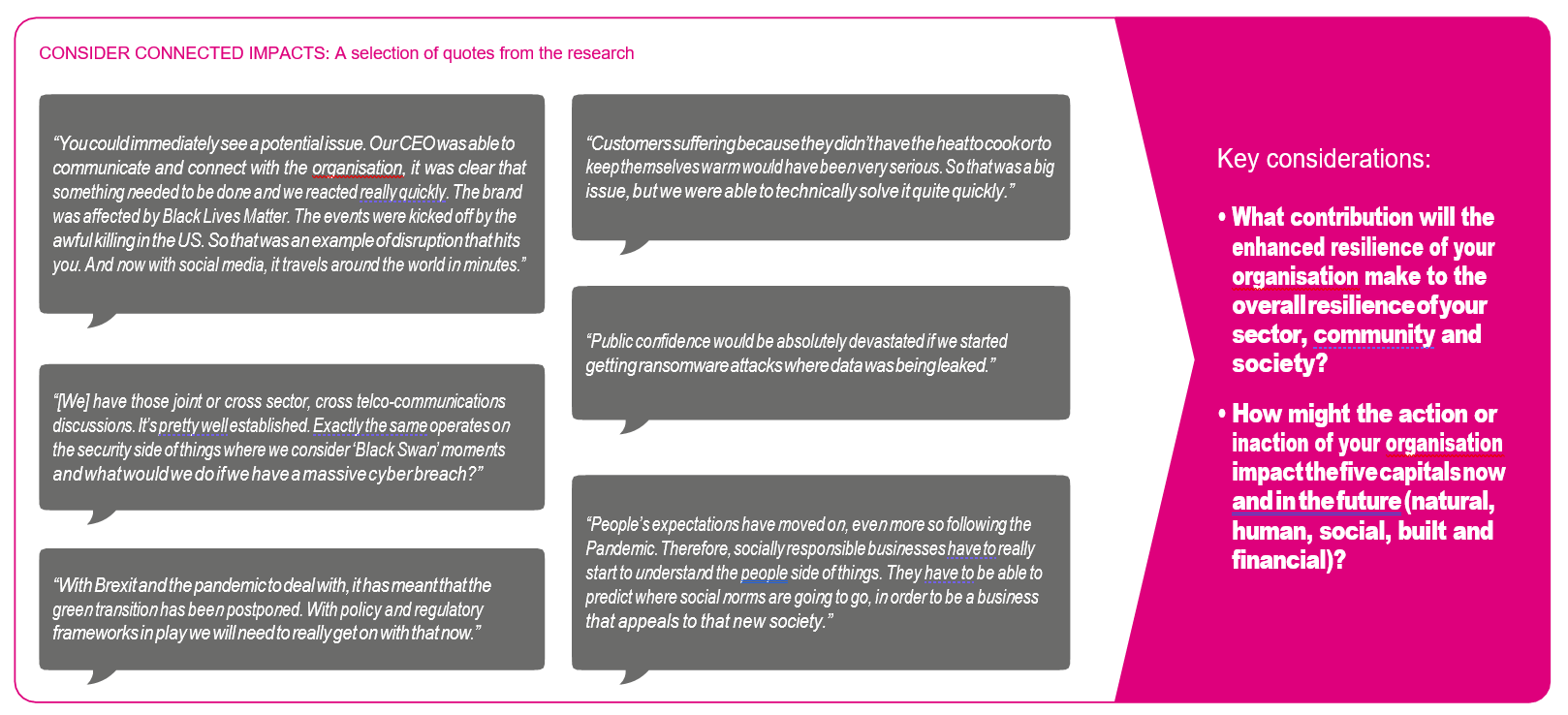

2. Consider connected impacts

Leaders put resilience at the heart of the new social contract by considering impact to all the components of the ‘ecosystem’ in which it operates. These ‘five capitals’ are natural, human, social, built and financial, along with their interdependencies. Considering the connections between the ‘five capitals’ helps organisations assess the real impact of disruption, providing a much more complete way of strengthening and assessing resilience.

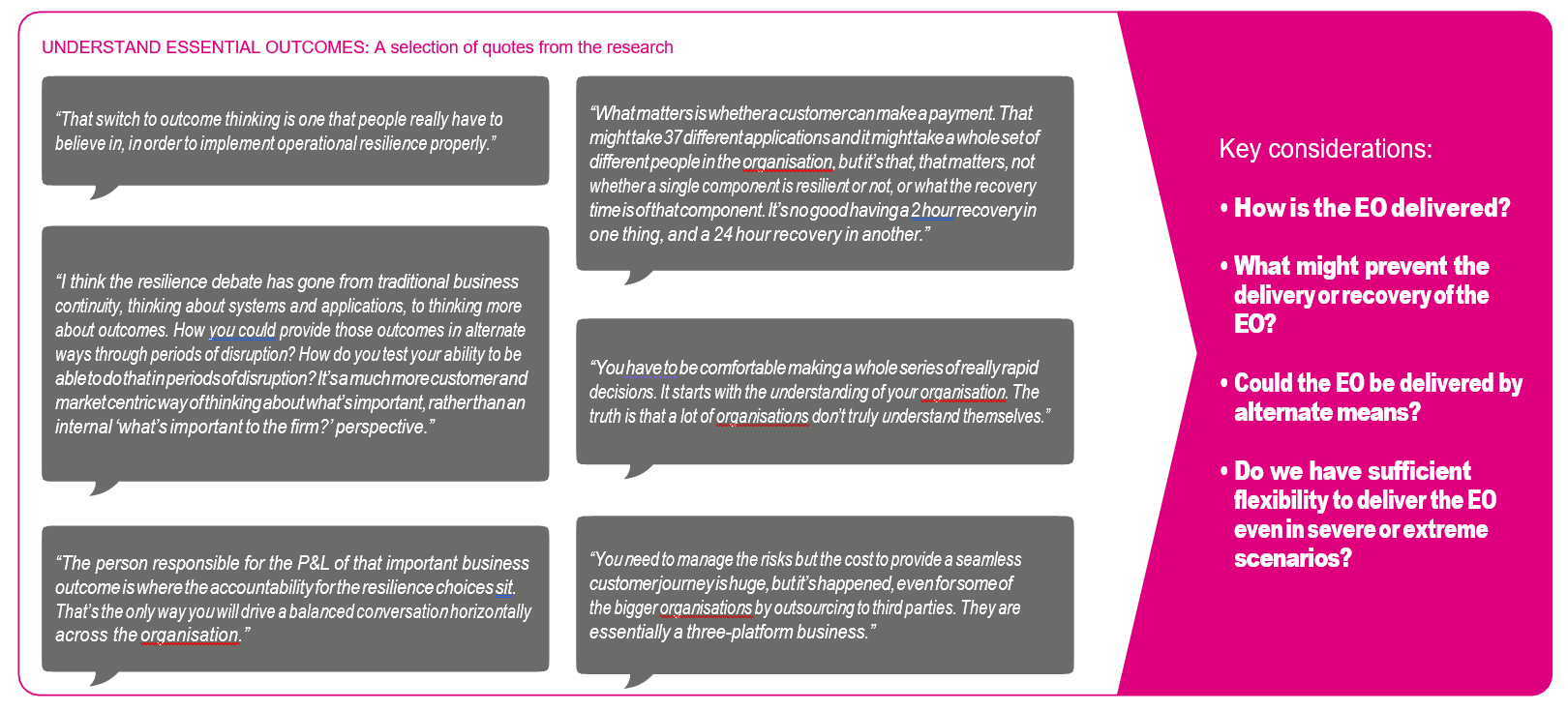

3. Understand essential outcomes

Resilience requires a deep understanding of how essential outcomes are achieved, from end-to-end and surface to core, to detect vulnerabilities. An outcome-focused perspective allows organisations to examine alternative means of meeting customer or other key stakeholder’s expectations in the event of a disruption. Dealing with more complex and severe scenarios means adjusting from a pre-planned recovery of asset approach to a much more adaptive response, prioritising essential outcomes – this requires flexibility in both mindset and design.

4. Define impact thresholds

A key lesson learnt from the building of financial resilience after the financial crisis in 2008 is the setting of financial impact thresholds (e.g. liquidity levels and capital adequacy ratios) and then stress testing these against severe, but plausible scenarios. This lesson is now being applied to operational resilience in the financial sector. The same approach could be applied to all five capitals. Organisations that apply this lesson will invest more wisely in their resilience and are better placed to deliver across the five capitals.

5. Balance strategic choices

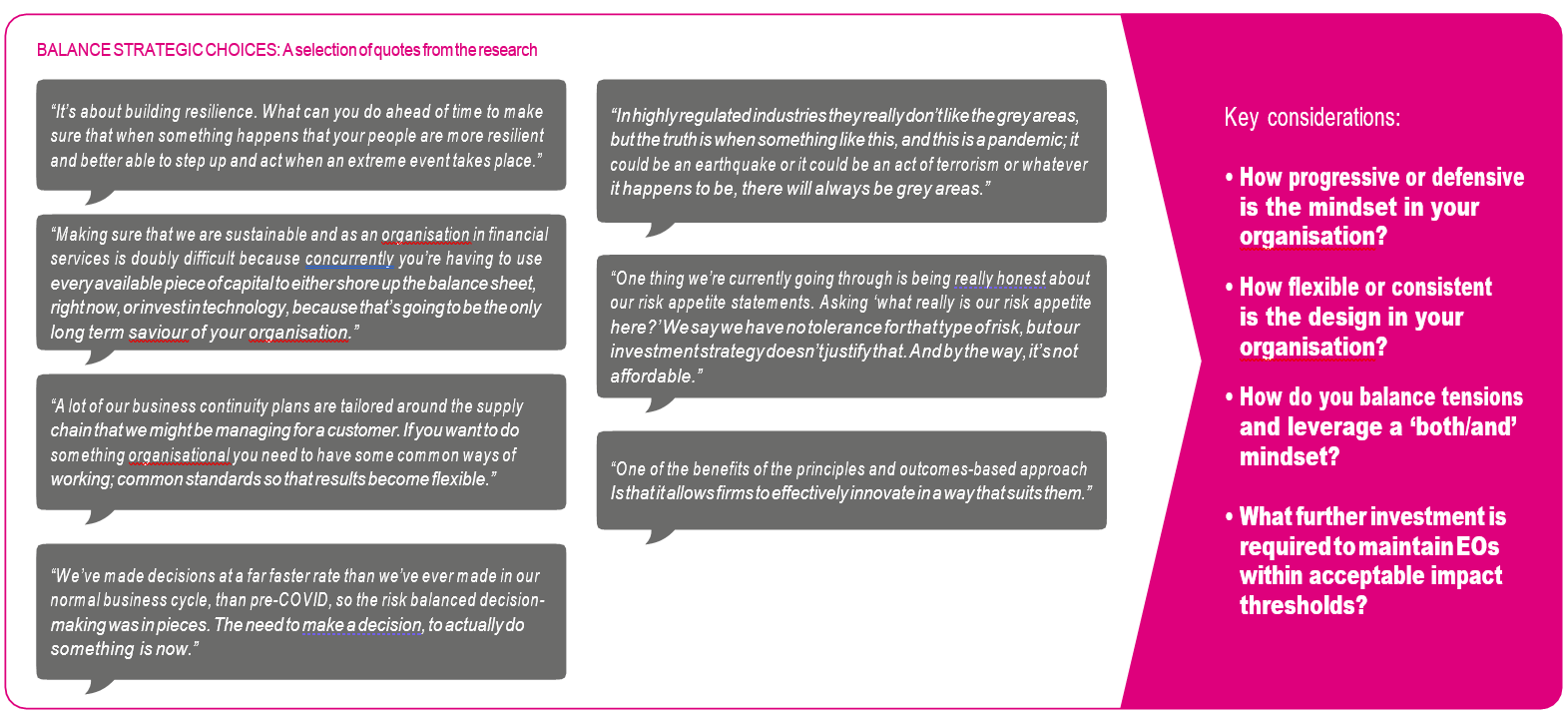

Research¹ has revealed that resilience programmes vary on two key dimensions: mindsets that are defensive or progressive; and designs that favour consistency or flexibility. This creates four resilience strategies. Neither of these strategies is right or wrong. But a preoccupation with any singular approach can create blind spots and vulnerabilities, enhancing the potential for disruption and crises. Resilient organisations find the right ‘fit’ for their environment and balance tensions.

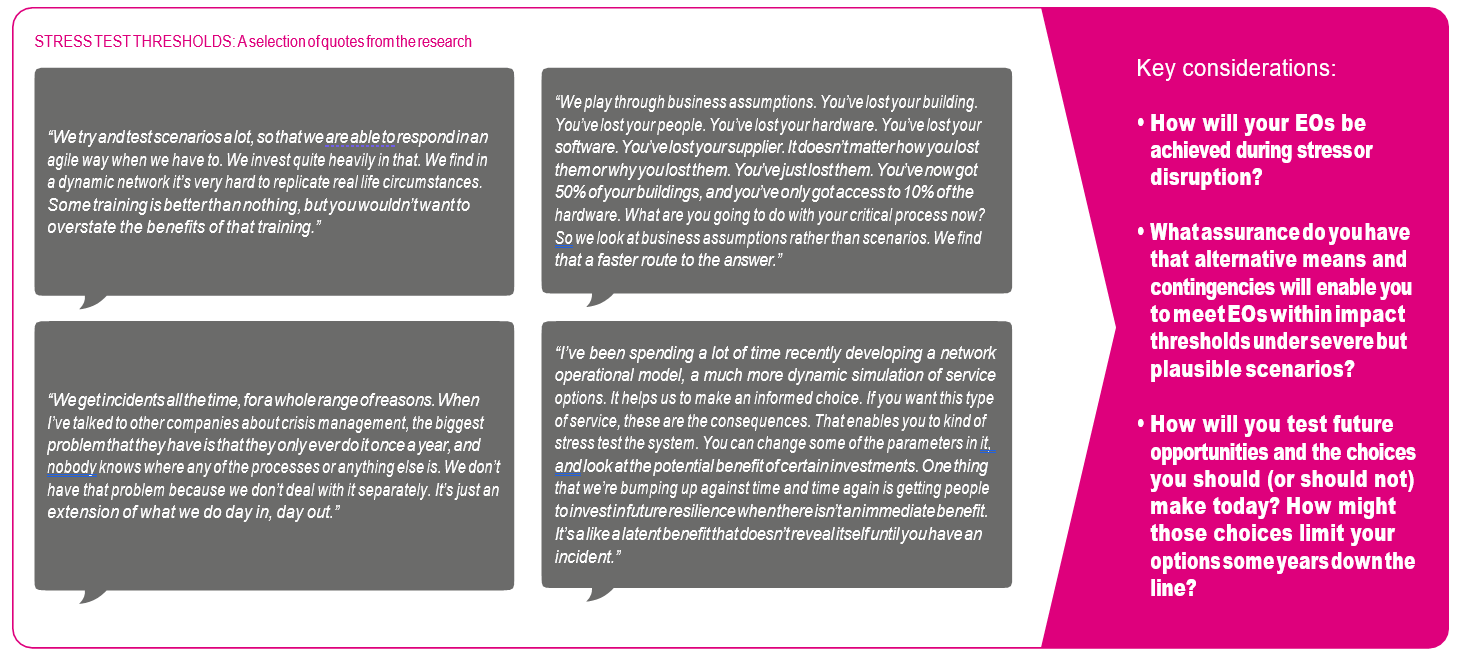

6. Stress test thresholds

Using stress tests, an organisation can explore whether the organisation can remain within acceptable thresholds under various severe but plausible scenarios. Stress testing is vital to help leaders make the investment decisions required to maintain essential outcomes within acceptable tolerance thresholds. This approach has proven benefits for financial resilience. Using digital twin techniques, ‘what if’ scenarios can be used to test assumptions, assess contingencies and outcome recoverability. This approach doesn’t have to be too complicated or costly to achieve real benefits.

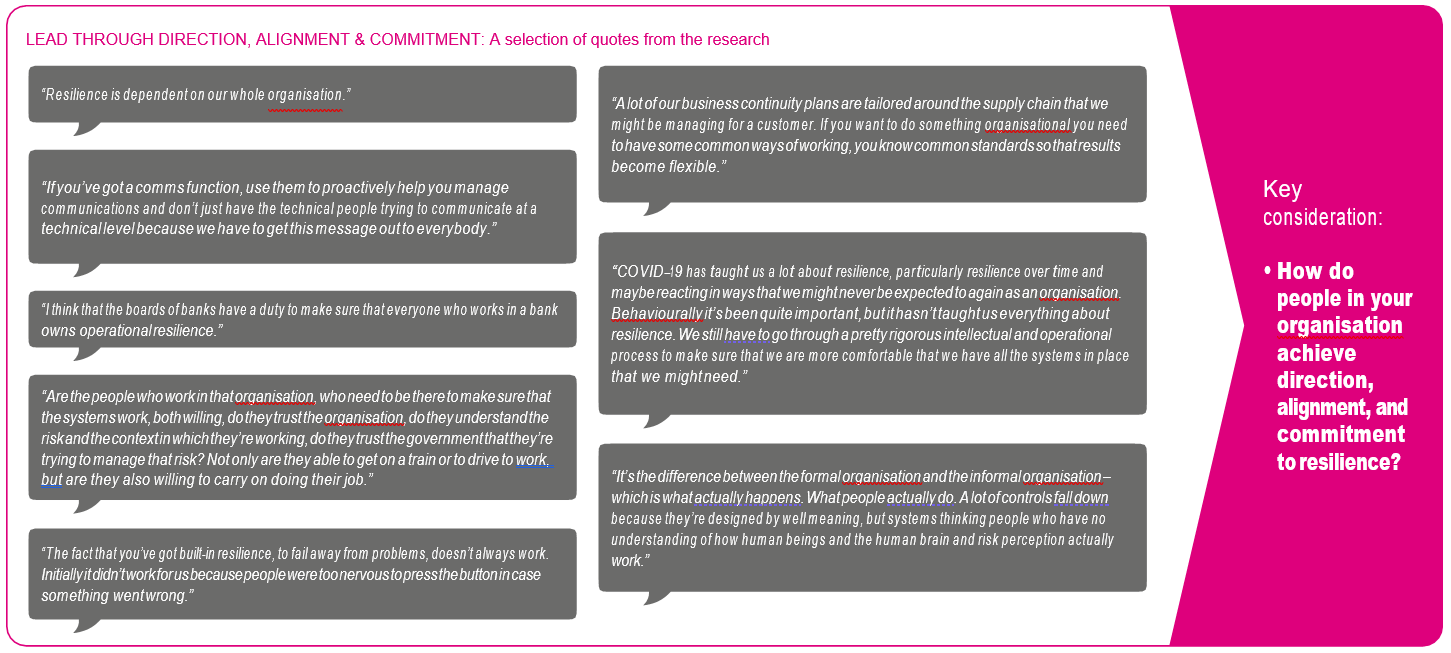

7. Enable adaptive leadership

Leadership is crucial to achieving direction, alignment, and commitment to resilience. The development of resilience is an adaptive rather than a technical process. People need to take on new roles, new relationships, new values, new behaviours, and new approaches to work. As environments become more uncertain and ambiguous, the leaders need to enable a culture of adaptation and collective action.

Seven recommendations for organisations

- Discuss future failure to avoid complacency and instil ‘futures thinking’. Ask what if? Ask what next? Encourage your people to speak up.

- Consider the connections between the ‘five capitals’ (natural, human, social, built and financial) to understand the potential impact of disruption on your stakeholders, your organisation and on wider society.

- Understand what is important to your stakeholders and to society, the ‘essential outcomes’ (EOs) that require a high degree of resilience.

- Set impact thresholds for EOs to determine tolerable limits that should not be breached, considering the impact on all five capitals.

- Make strategic choices about resilience interventions by balancing: control, agility, efficiency and innovation.

- Conduct stress testing to determine whether you are able to remain within your impact thresholds irrespective of the threat.

- Enable direction, alignment, and long-term commitment to resilience through a culture of adaptation and empowerment.

- These practices can help organisations to achieve better readiness, more responsiveness, faster recovery and greater regeneration (the 4Rs of resilience).

Three recommendations for Government

- Enhance access for organisations of all types to evidence about the multitude hazard-related risks, including the use of futures thinking, foresight techniques, and real-time notification and early warning systems.

- Align resilience policy across economic, health, social, infrastructure and environment goals to build system-wide preparedness to complex threats.

- Use regulation to challenge organisations to demonstrate their resilience and to consider their contribution to the resilience of their sector and to society.

The report brings coherence to the approach necessary to develop, assess, and improve organisational resilience. However, every organisation is unique. One solution doesn’t fit all. This report will help leaders make the unique and necessary choices to achieve organisational resilience in the context of their organisation. We offer a new maturity model to help organisations self-assess their current resilience and chart their improvement journey.

Many organisations express the desire to measure resilience. The drive to justify the investment and monitor the success of resilience programmes is gaining urgency. We discuss how this could be achieved by evaluating the 4Rs of resilience: readiness, responsiveness, recovery and regeneration. This report is for senior executives and leaders accountable for setting and implementing their organisation’s strategy. It will also be useful for directors and those in operational roles responsible for managing functions or business units that deliver essential business services.

Introduction

Resilience has been pushed firmly toward the top of the agenda for boards and senior management teams of organisations of all types. But how can resilience be developed? Who does it well, and what can we learn from them? What are the practical steps necessary to strengthen resilience for long-term success? As a leader, what more could you do to develop resilience for your organisation?

To address these questions, we conducted twenty five in-depth interviews and four focus groups with leaders (boards, senior executives, policymakers and resilience directors) in organisations seen as world-leading in terms of their resilience programmes. At their request, all quotes presented in this report are anonymised. The sectors involved include water, energy, environment, transport, manufacturing, food retail and logistics, defence and security, information and communications technology (ICT), infrastructure and hospitality.

Over fifty practitioners and academics contributed insights, experiences, and examples that helped shape our thinking and this report. We supplemented our data with a review of recent publications and reports on organisational resilience and referred to relevant literature and thought leadership.

Cranfield University conducted the research on behalf of the National Preparedness Commission (NPC). The research was undertaken in partnership with Deloitte, who sponsored and contributed to it.

Our research found that leaders have traditionally relied on a systematic process to assure themselves and their boards that they have taken reasonable steps to build resilience. They have invested in a system of standards, including enterprise risk management (ERM), business continuity management (BCM), crisis incident management (CIM) and disaster recovery (DR). The hope is that these systems could help predict, prevent, and protect the organisation from threats and help the organisation bounce back from disruptions and crises.

Organisations often employ BCM specialists and teams to make their programmes as ‘bulletproof’ as possible, hoping that incidents will mostly disappear when a rigorous programme is in place. If something does go wrong, the hope is that having a comprehensive plan based on best practice management standards will help convince regulators and the public that their actions were reasonable and responsible. The improvements made in enhancing resilience over the years has been laudable.

Most of the time, the existing system works. Every day, normal business processes cope with the myriad of minor disruptions and issues. More significant incidents are usually covered by the

organisation’s business continuity plan (BCP). Resilience is assured by plans, procedures, and compliance and focuses on recovering the organisation’s assets in a crisis. However, complex and more severe events are forcing organisations to be agile and fluid in their approach to respond and adapt effectively to unfamiliar or challenging situations. Many leaders now realise that relying on a reactive strategy is not enough on its own to meet the potential scale and pace of change imposed by sudden shocks and future challenges. Organisational resilience incorporates BCM but requires more than a reliance on procedures to recover assets (what if they can’t be recovered within reasonable timeframes, or

at all?).

Organisational resilience isn’t purely defensive in orientation. It is also progressive¹, building the capacity for agility, adaptation, learning, and regeneration to ensure that organisations are able to deal with more complex and severe events and be fit for the future. The challenge of adaptation is exacerbated by today’s uncertain, complex, highly demanding and rapidly changing context in which organisations operate. Recent crises have raised serious questions about how rapidly organisations can adapt to changing threats, disturbances, and perturbations (such as a pandemic, climate change, or cyber-attacks).

With COVID-19, many organisations muddled through the crisis to deliver services. Still, with others, the response was marked by greater cross-functional collaboration and highly participative environments in which people at all levels took and felt personal responsibility for resilience. Many organisations told us that the pandemic accelerated new business initiatives, which previously would have taken years, not months. However, the reactive approach to a crisis has profoundly impacted wellbeing as well as the bottom line.

Leaders told us that the next crisis might be very different, and another government bailout may not be forthcoming. Therefore, they will take more responsibility for their resilience and invest in future resilience now.

Through our research, including the learnings from the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent strengthening of financial resilience, we found seven practices that make organisations more resilient. In the section that follows, we describe each of these resilience practices and highlight key considerations for leaders. These seven practices are then developed into a new methodology of how to

build organisational resilience. Next, we offer a new maturity model to help organisations self-assess their current resilience and chart their improvement journey. Then, we offer some thoughts on the thorny issue of measuring resilience.

Resilience Reimagined: Seven Resilience Practices

1. Discuss future failure

Failures of Imagination

Every leader in our research commented that we are entering a new period of uncertainty and change, with an ever-increasing possibility of failure. The threat landscape appears to be growing in complexity and volatility with the emergence of sudden shocks such as a pandemic, extreme weather events, terrorism, and long term intractable challenges, such as climate change, meeting the needs of an ageing society and tackling inequality. A growing reliance on inter-dependent technologies also exposes businesses to emergent threats and systemic/networked risks.

Conventionally, risks are assessed from the likelihood of their occurrence versus their potential impact. Risks are classified on a risk register. A risk appetite is the amount of risk that an organisation is willing to take in pursuit of its strategic objectives and goals. The focus is on named risk types typically classified as minor, moderate, high, or severe. Organisations then define the effects and actions

or interventions which would reduce the inherent exposure to the risks. Risks are assessed periodically, often annually.

Government can play a role in enhancing access for organisations of all types to evidence about the multitude of hazard-related risks, including the use of futures thinking, foresight techniques, and real-time notification and early warning systems.

COVID-19 SHOULD NOT HAVE BEEN A SURPRISE

Pandemic influenza has been identified as the highest consequence threat on the National Risk Register² since the first edition was published in 2008. In a 2015 TED talk, Bill Gates³ warned that we are woefully underprepared for the ‘next outbreak’. He appealed

to national governments and businesses to work together to build a global warning and response system for epidemics. We were not adequately prepared. Why?

Inspiration for our title ‘Resilience Reimagined’ comes from a striking statement on page 344 of the 9/11 Commission Report⁴: “Imagination is not a gift usually associated with bureaucracies… It is therefore crucial to find a way of routinizing, even bureaucratizing the exercise of imagination. Doing so requires more than finding an expert who can imagine that aircraft could be used as weapons”.

Karl Weick⁵ argues that complex and severe events are often a failure of imagination, “the world is rendered more stable and certain, but that rendering overlooks unnamed experience that could be symptomatic of larger trouble.” We need to reimagine resilience as we enter a new period of uncertainty and change, with an ever-increasing possibility of crises.

We have all heard leaders who downplay threats: “It hasn’t happened yet”, “We are different”, “It is so unlikely”, “It can’t happen here”, “Too big to fail’. In some organisations, people lose psychological safety⁶. They fear that they will be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns or mistakes. Talking about potential problems can be perceived as ‘negative thinking’ in some organisations – but on the contrary,

discussing future failure will help ensure a more positive outcome.

There is a concept known as normalcy bias in psychology, which explains why people underestimate both the possibility of an incident and its possible effects. Experts attribute the problem to people’s tendency to interpret warnings optimistically. Any worrying indications that something terrible may happen are denied or trivialised. It results in the inability of people to cope with a disaster once it occurs. It also helps explain why individuals and organisations have difficulties reacting to something they have not experienced before. The result is that many organisations sleepwalk into failure¹.

To overcome the mindset trap of normalcy bias and encourage people to discuss future failure, renowned scholars including Daniel Kahneman, Gary Klein, and Karl Weick promote the value of ‘prospective hindsight’. They recommend imagining future failure and looking back to generate better decisions, predictions, and plans.

In their book Managing the Unexpected⁷, Karl Weick and Kathleen Sutcliffe emphasise ‘preoccupation with failure’, which is a mindset that things WILL go wrong, so there is a need for continuous attention to anomalies that could be symptoms of potential problems in a system. Resilient organisations accept that their designs, plans and operations, are fallible – they ask what if? They also anticipate and make less complacent assumptions about future issues – they ask what next?

Leaders told us that the benefits of this approach were:

• Assuming the incident has already occurred, rather than pretending it might happen, helps to dampen excessive optimism.

• Looking back from a known outcome makes it seem more concrete and likely to happen, which motivates people to devote more attention to explaining it.

• It helps people overcome blind spots – it forces people to see things from different perspectives, especially when you have enough cognitive diversity in the room.

• It allows people to speak up who might remain silent for fear of being labelled a pessimist or being punished for speaking up with a dissenting view.

• Purposefully surfacing potential problems challenges the illusion of consensus and the desire for harmony and conformity within a group.

• It draws attention to what might be the ‘weak’ signals, like the canary in the coal mine, of a potentially significant emerging problem.

More and more organisations are now using premortems to encourage people to discuss future failure and ensure that their essential outcomes get the scrutiny they need. The premortem involves placing yourself in the future, pretending that a failure has already occurred, and looking back and inventing the details of why it happened. The aim is to identify every problem with even a remote chance of occurring that could derail the essential outcome (see the text box below for an example).

Organisational resilience in practice: conducting a premortem

One organisation conducted a premortem by asking the entire team, who were involved in delivering an essential service, to start by writing a future newspaper headline. They were asked to imagine an embarrassingly disastrous failure. They were encouraged to think ‘outside the box’. The groups then voted on the most dramatic but plausible incident. The next session involved working out how the incident could happen. A visual representation called a ‘mess map’ was produced, revealing a broad set of latent issues, vulnerabilities and failures involving people, processes, technology, facilities and information across the incident timeline. The final session involved a creative ideas generation process to identifying potential actions that could mitigate the issues in question. The end results were a more resilient service and a more resilient team that was more aware of the challenges it was facing.

Scanning and Horizon Scanning

Some organisations use proprietary scanning, notification and early warning systems, including Artificial Intelligence and business analytics to identify threats (e.g. terrorist incident, weather event, public disorder) to which the organisation must respond. These systems aggregate and filter risk event data from global news, law

enforcement and social media. They then produce a situation report for risk events about where employees, facilities, suppliers and other operational assets are so you can instantly see the potential impact. These scanning platforms produce an integrated picture

of external threats and events on a real-time basis, overlaid with an organisation’s people, assets and supply routes, to enable timely assessment of emerging issues anywhere in the world.

Foresight also involves the search for new possibilities and opportunities. Examining possible futures helps organisations to anticipate future consumer/customer needs which can guide

innovation and identify new markets that do not yet exist. Many of the organisations involved in this study use foresight methods, such as scenario planning, to generate a new ‘picture of the future’. A key point is that you can’t predict the future, but leaders told us that the key is not necessarily getting the right vision or picture of the future but fostering the process of anticipating. Foresight helps to condition individuals to be mentally prepared for uncertainty and change. Strategic foresight provides guidance for strategic actions being taken today – not only what to do, but how and when to do it. A positive outcome of foresight exercises is also the identification of ‘success stories’ or examples of ‘promising practice’, which can serve to inspire others, and which can be useful benchmarking aids in highlighting and disseminating good practice.

2. Consider connected impact

Leaders pointed to the central role resilience plays in the new ‘social contract’ – the arrangements and expectations, often implicit, that govern the exchanges between individuals and organisations and Government.

Leaders are starting to recognise that resilience is necessary to achieve their purposes and obligations concerning all the components of the system in which we live. These five capitals⁸,⁹,¹⁰ are financial, human, built, social and natural, along with their interdependencies and feedback:

| Financial | Strive to expand the gains achieved through economic and productivity growth, ensure that organisations thrive in a changing environment, and are fit for the future¹. They also address issues that threaten the financial integrity of the organisation, market, or sector. |

|---|---|

| Human | Enhance the skills and abilities of people and build capacity. They also have a duty of care to reduce harm to people, improve well-being, and tackle the challenges individuals and society face, especially those most vulnerable. |

| Built | Safeguard the security and soundness of infrastructure, critical systems, plants, energy, transportation, communications infrastructure, technology, supply chain, and other built assets. |

| Social | Maintain trust with customers, the public and other stakeholders by delivering high service reliability levels and responding effectively to disruptions. Cooperation and reciprocity involved in relationships within and outside the organisation matter. |

| Natural | Protect habitats and ecosystems, and natural resources by prioritising environmental sustainability, zero carbon and circularity. |

Resilience is fundamental to the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) and Diversity and Inclusion and Belonging (DIB) agendas. Resilience is also rooted in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for industry, innovation and infrastructure, as well as Sustainable Cities and Communities, to develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure, including regional and trans-border infrastructure, to support economic development and human wellbeing. The priorities of the Government are also aligned with building resilience across the five capitals. Economic, health, social, infrastructure and environment goals are all dependent on each and every organisation being resilient.

No organisation is resilient unless the system is resilient

The five capitals model ⁸,⁹,¹⁰ can be used to allow organisations to examine five connected impacts (Table 1) for every severe but plausible scenario. The model can also help organisations examine their connected resilience and consider what needs to be done to maximise the value of five capitals, manage ‘trade-offs’, and avoid weakening them. In many organisations, these impacts are labelled people, reputational/regulatory, operational, environment and financial.

| Five capitals | Key impacts |

| Human capital (e.g. skills, capabilities, experience, know-how, tacit knowledge) | People impact (e.g. harm, wellbeing, health, absenteeism, turnover) |

| Social capital (e.g. networks, norms, values and understandings that facilitate cooperation, collaboration and community) | Reputational/regulatory impact (e.g. reputation, confidence, trust, complaints, customer loyalty, regulatory fines, contractual penalties, market integrity) |

| Built capital (e.g. buildings, water processing, manufacturing and processing plants, energy, transportation, communications infrastructure, technology) | Operational impact (e.g. machine downtime, system outages, capacity utilisation, on-time delivery, yield, data loss) |

| Natural capital (e.g. materials, soil, air, water, plants and animals) | Environmental impact (e.g. biodiversity loss, pollution, deforestation) |

| Financial capital (e.g. cash, assets, credit, and other forms of funding that build wealth) | Financial impact (e.g. profitability, liquidity, cash flow, solvency, valuation) |

A common mistake is to assume that specific issues in one of the capitals will have a corresponding impact. E.g. a problem with built capital (flooded building) will have only a related operational impact. This overlooks the other system impacts that must be considered. Impacts will vary depending on the situation, for example, a cyber attack’s human impact may be limited to inconvenience to customers and employee stress in one context. Yet, in another situation, such as a hospital, the human impact could be severe. There are some recent examples where critical infrastructure providers have been attacked by ransomware, and their critical control systems have been accessed and in an extreme situation, this could cause an environmental impact.

The Deepwater Horizon incident involved the failure of built capital (a well blowout that caused the explosion), which was caused by a combination of human (error), social (relationships between BP, the company that leased the rig and owned the licence to drill, Transocean Ltd, the drilling rig owner, and cement contractor Halliburton Energy Service) and operational factors such as a flawed well plan that did not include enough cement. The corresponding impact was felt across all five capitals: human (11 people lost their lives, multiple injuries), environmental (described as the worst ecological disaster in the United States), reputational damage, and financial impact (estimated to exceed $60bn).

Reputational impacts can be unpredictable. Our previous work¹¹ reveals that ‘some events, it appears, can be converted into crises or disasters as long as there is political will or journalistic desire to do so. The press and 24-hour television news channels appear ever ready to declare a crisis in the interests of a dramatic story’. Incident investigations and public inquiries often point to systemic failures rather than individual human errors, highlighting organisational and management factors as the leading causes of crises¹¹.

The preparedness and responses of the governments, regulators, and management teams involved in such events are scrutinised in courts of public, media, and political opinion. Such incidents can provoke uncertainty, pessimism, and a general loss of trust in organisations and Government.

By examining connected impacts across three timelines (short, medium and long), the five capitals framework also helps us become more aware of how our individual and collective actions today shape the future. Mapping connected impacts from the three horizons’ perspectives can generate conversations that foster understanding and future consciousness as the basis for collaborative action and transformative innovation. Without this future-looking perspective, you may fail to consider long term consequences and may be missing out or not capitalising on emerging trends and insights where fresh growth opportunities reside. Organisations should consider the potential impacts of disruption across all five capitals and the effects’ timeframe, as shown in Figure 1.

Using the five capitals model for decision-making can lead to improved resilience and avoid negative consequences. Conventional processes tend to deprioritise environmental and social elements and promote siloed sequential short-term development. Effective resilience requires a connected approach across the five capitals.

3. Understand essential outcomes

“People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!”

Theodore Levitt

All too often, we focus resilience efforts on improving the resilience of the asset (drill) and processes (drilling) and not the outcome (producing holes), creating a misalignment with stakeholder needs.

Resilient organisations prioritise the things that matter by defining the essential outcomes (EOs) expected by a customer, end-user or key stakeholder. The EOs approach helps organisations focus on what customers or the public need most in a crisis and how the outcome, not just the asset, could be recovered.

Essential outcomes are the ‘what’, process and assets are the ‘how’.

An essential outcome is an actual thing that customers want organisations to make happen (producing holes). They are the outcomes of critical products and services that an organisation provides to its customers or end-users. EO have a chain of activities that make up a process (e.g. drilling), from initiation to delivery of the process, and determine all resources (e.g. drill) critical to delivery. EOs are the outcomes that impact the attainment of strategic goals and targets, but are not the strategic goals themselves.

• EOs are not internal functions (e.g. HR or IT Department).

• EOs are not processes (e.g. staff payroll).

• EOs are not assets, resources or facilities (e.g. supplies, factories, offices).

• EOs are not strategic goals and targets (e.g. increase revenue, reduce costs).

An example of an EO for a retail organisation might be making products available that the target consumer expects and desires. There might be several processes, involving multiple assets, resources, facilities and suppliers for the EO to be accomplished. The failure to deliver the EO could directly impact revenue, profitability, reputation/brand and the achievement of other corporate targets.

EOs are externally focused and are different to business processes which tend to be more granular and internally focused. EOs often involve multiple assets and business processes. Crucially, resilient organisations focus on the recovery of the EO, not just the asset’s recovery. If a disruption occurs, it may not be possible to recover the assets (drill) or the process (drilling). Yet, it may be possible to explore alternate means of delivering the EO (producing holes) and meet end-user expectations. Resilient organisations create flexibility by design in how essential outcomes can be achieved, even if severe or extreme disruption occurs.

Leaders told us that the shift to an outcome perspective was challenging. It requires a fundamental mindset shift from thinking solely about what is important for the executives and investors to what is essential for the end-user: a customer, a member of the public, a client, a stakeholder. It requires empathy to understand the end user’s experiences, hopes, fears and desires about the outcome. What failure to deliver the outcome means to those customers and end-users.

The extent to which you understand and empathise with your users ultimately determines the resilience of your outcomes. Often people closer to the client are better placed to define EOs than those at the top of the organisation. Delivering EOs often crosses several business units, departments, and functions. Some organisations in our research assign accountability for the essential outcome from end-to-end.

Mapping EOs

We often think of resilience as the absence of disruptions (or as an acceptable level of risk). In this perspective, resilience is defined as a state, where as few things as possible go wrong. Crucially, this view does not explain why EOs almost always go right. An alternative

to the conventional approach of trying to make ‘as few things as possible go wrong’ is to try to make ‘as many things as possible go right’¹². Thus, the mapping approach should start with looking at what you usually do well.

Organisations can identify and document the necessary resources (i.e. people, processes, technology, facilities, suppliers or third parties, and information) required to deliver each of their EOs.

Leaders told us that a critical element of resilience is understanding how each essential outcome is provided from end-to-end and from surface-to-core. The objective is to know how the system is expected to work and what makes it work in practice.

Organisations map the important process steps and define which resources enable them to be delivered. The maps must be at a level of detail that helps identify the resources contributing to each stage’s delivery and criticality. Resilient organisations pay attention to the workarounds that their employees need to do as sources of insight into the process’ vulnerabilities.

Customer journey mapping is a framework and visual approach for categorising, defining, capturing and organising the touchpoints that comprise the customer experience. Creating a customer journey map involves ethnography, observation, stakeholder narratives and data. Customer interactions and experiences over time are mapped, including what customers are doing, thinking, and feeling along the way.

Journey maps have traditionally been used as a design tool to define ‘what happens’ and ‘how it is experienced’ by stakeholders. They highlight the pain points and opportunities for innovation to improve the customer experience. It can create a shared understanding of how a given function might contribute to the resilience of EOs.

Where journey mapping focuses on exposing the end-to-end of the user’s front stage experience, blueprinting examines the backstage processes, resources, and third party support required. It exposes the surface-to-core of the EO the how it is delivered and operated.

Blueprinting provides an essential frame of reference to capture and understand the inherent strengths and vulnerabilities of an EO in a visual way. It can inform stress testing and strategic decision making. Returning to our drilling analogy, if you only have one means of making a hole – with a drill, then you will only be able to achieve the outcome if you can recover the asset; but what if you can’t recover it? Is there another way to make a hole, and is this built in to our resilience by design?

A visual representation of an EO can be produced by the journey mapping and resilience blueprinting involving diverse contributions from a multi-disciplinary team. The benefits of blueprinting include:

• Forming a stable, shared understanding of an essential outcome.

• Assembling the contributing factors into a coherent causal diagram.

• Examining single points of failure/lack of alternative paths, crucial interfaces, critical steps (points of no return), and ‘risk important’ actions.

• Exploring how factors are interconnected across borders and boundaries.

• Incorporating different worldviews and data from diverse sources.

• Producing a rich, visual picture to share with colleagues.

• Highlighting problem areas that should be addressed to prevent incidents from occurring in the future.

4. Define impact thresholds

Not all outcomes are equal in importance.

Prioritising direct resources proportionately to ensure enhanced resilience of those outcomes that are considered by stakeholders to be ‘essential’, and to a level (e.g. time, volume, value etc) that in a crisis situation is deemed acceptable. Prioritisation also helps focus investment decisions on areas and activities where there is a significant potential to enhance resilience. Resilient organisations define the essential outcomes before disruption hits, ensuring that they do not need to make these strategic choices amid a crisis.

With a 2018 publication¹³ of a joint discussion paper on operational resilience, the Bank of England, Prudential Regulation Authority and the Financial Conduct Authority (together the ‘Supervisory Authorities’) mandated the impact tolerances approach for financial institutions and financial market infrastructures.

Supported by a regulatory framework for better resilience, this sector is becoming much more mature in its approach to resilience and operational preparedness. This has allowed financial institutions to adapt and cope at speed with disruption. The regulators are challenging organisations to demonstrate their resilience and to consider their contribution to the resilience of their sector and to society.

A key lesson learnt from the building of financial and operational resilience in financial services is the definition of ‘important business services’ that, if disrupted, would:

- create harm or detriment to an external end-user or another key stakeholder

- put at risk the very existence or viability of the organisation

- threaten the stability of the market, sector and broader system.

A similar approach could be taken to define essential outcomes (EOs) across the five capitals. An essential outcome is one that, if disrupted, would:

- create harm or detriment to an external end-user or another critical stakeholder (people)

- breach a legal or contractual requirement or cause a severe loss of confidence and trust in the organisation (reputational)

- put at risk the very existence or financial viability of the organisation or threaten the stability of the market, sector and broader system (financial)

- create an adverse or irreversible impact on the natural environment (environmental)

- fail to provide what customers or the public need in a crisis or are difficult or slow to recover and have limited or no available alternative (operational).

When examining resilience more widely, alternative means of delivering the service might exist outside the organisation’s. For example, think of withdrawing cash as the essential service outcome a customer wants to achieve. An ATM is one of the channels (services). If the ATM option is disrupted, customers may also be able to withdraw cash at a post office, branch or even food retailers.

There is system redundancy resulting in substitutability/flexibility for customers to achieve the desired outcome (withdraw cash) – this provides increased resilience under certain circumstances. While these alternatives mean that the EO is resilient, the ATM’s failure may nevertheless negatively impact the provider’s reputation.

Defining outcome priorities upfront helps focus effort and investments in resilience more effectively and means that crucial decisions are taken ahead of a crisis. Imagine a disruption meant that you could only operate at 80% capacity. Could you still deliver all of your EOs? What about at 60% or 40% capacity? At what point would you need to stop delivering an EO? At what point would you divert resources from one EO to ensure the delivery of another? Ultimately, there will be a threshold level where your resilience will be compromised, and choices need to be made about which EOs are most important. Resilient organisations determine these threshold levels and make these choices ahead of the crisis.

However, an adaptive response also allows for predetermined priorities to be reset when necessary. For example, government- backed business loans’ disbursement became a priority for banks when COVID-19 hit, but this wasn’t in their predefined list of priority outcomes. Indeed this outcome didn’t even exist until the pandemic response unfolded. However, banks were able to adapt their response, and they had sufficient flexibility in their processes to deliver quickly.

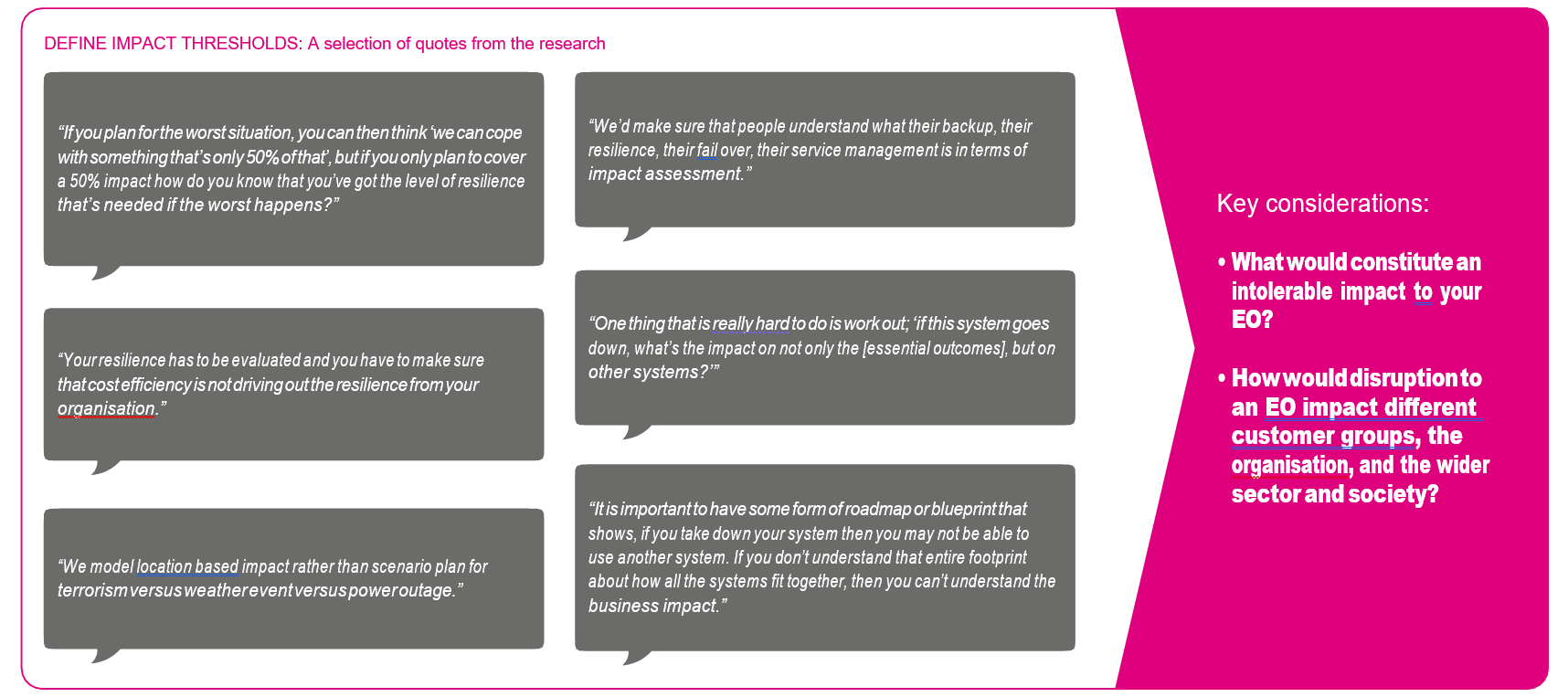

Organisations can define their own resilience thresholds, which ultimately entails quantifying how a disruption could impact different customer groups, the organisation, and the wider sector and system. Leaders in our research described the differences between a traditional risk-based approach and this impact tolerance approach (Table 2).

Table 2: The impact tolerance approach compared to the traditional risk management approach.

| Traditional risk-based approach | Impact threshold approach |

| Primarily internal – impact on the organisation’s objectives | Primarily external – impact to an external stakeholder and broader system |

| Focus on named risk types | Focus on essential outcomes |

| Appetite for and classification of risks: minor, moderate, high or severe | Thresholds of what is tolerable/acceptable |

| Likelihood of the risk occurring | Assumes the risk has occurred |

| Defines effects and actions or interventions which would reduce the inherent exposure | Defines effects and actions or interventions which would reduce the inherent exposure and factors in recoverability |

| Often uses words such as ‘significant’, ‘substantial’, ‘some’, ‘extensive’, ‘damage’ that is open to interpretation and cannot be quantified. | Provides essential outcome measures |

| Updated and reviewed periodically (quarterly, annually) | Ongoing monitoring and review of the essential outcome. In some organisations, this involves feeding in live information to anticipate and prevent disruptions. |

It may be useful to examine the ‘business as usual’ functioning of the essential outcome (EO). Identify possible metrics to describe the EO’s typical functioning by measuring both outcomes and the resources/assets involved in the delivery process (i.e. inputs). Agreeing on a shortlist of appropriate metrics then becomes vital. They later form the basis on which impact thresholds will be set. Historical data for a given day plus data over an extended period (e.g. 12 months high and low) can then be collated. This helps to validate the impact thresholds that can still be maintained during demand peaks or troughs.

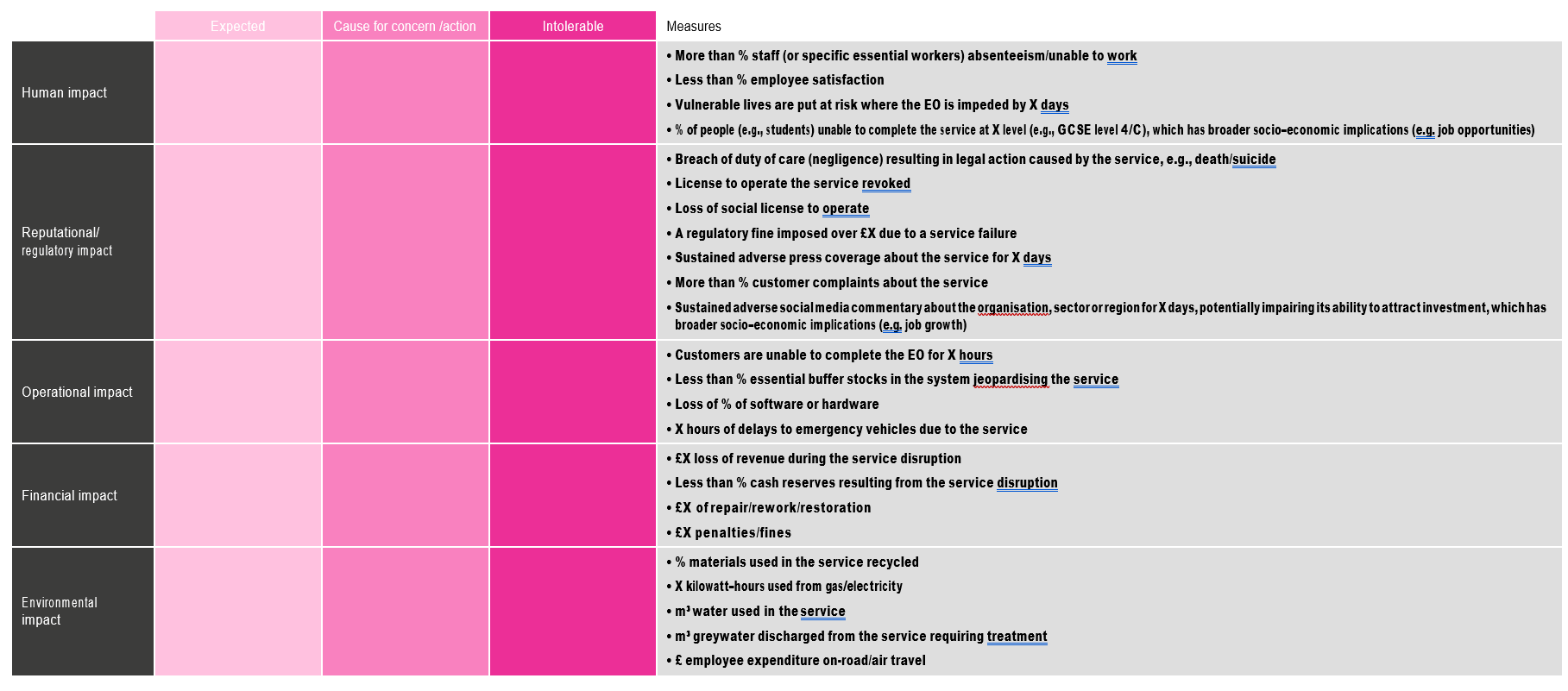

Impact thresholds will differ depending on the EO and the organisational context. Table 3 provides an example of possible thresholds for an essential outcome across the five capitals. Such an approach might be expanded to identify the expected levels and levels that cause concern and require action.

5. Balance strategic choices

Leaders make strategic choices and adjust organisational strategies and practices to fit contextual conditions.

However, they often struggle with balancing seemingly competing priorities including:

- assuring compliance to a prescriptive system of rules, regulations and standards, protecting people, reputation, assets, and the environment.

- responding to issues as they emerge with flexibility and agility, empowering people to take ownership of problems and formulate creative solutions.

- satisfying investor expectations, meeting productivity and efficiency goals and increasing capacity to meet the growing demand.

- innovating to keep pace with new technology, business models and consumer trends.

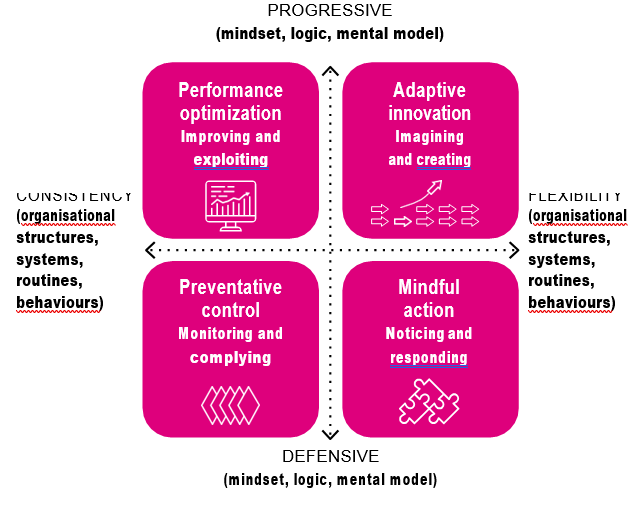

Our previous research¹ found that organisational resilience strategies differ on two core dimensions: mindset (defensive vs progressive) and design (consistency vs flexibility). The two dimensions form an integral part of a framework, which we termed the Strategic Tensions Model (Figure 2), which highlights four common strategies for achieving organisational resilience¹.

Figure 2. Strategic Tensions Model of Organizational Resilience. (Source: Denyer, D. (2017), Organizational Resilience: A summary of academic evidence, business insights and new thinking. BSI and Cranfield School of Management)

- Preventative Organisational resilience is achieved through robust risk management, physical barriers, systems back-ups, safeguards, and standards. The focus is on protecting the organisation from threats and predicting and preventing disruptions and crises. Preventative control is essentially a defensive strategy based on consistency and returning the organisation to its current state if there is a crisis.

- Mindful Organisational resilience is created by people who use their experience, expertise and teamwork to anticipate and adapt to threats. Responding flexibly to unfamiliar or challenging situations requires creative problem solving and expert improvisation. Mindful action is a defensive strategy based on flexibility.

- Performance Organisational resilience is formed by continually improving, refining and extending existing competencies and exploiting current technologies to serve present customers and markets more efficiently and effectively. It involves improvement within the current paradigm rather than creative ‘blue skies’ or ‘out of the box’ thinking. Performance optimisation is essentially a progressive approach based on consistency.

- Adaptive innovation. Organisational resilience is created through innovation and by developing new products, services or It is also the strategy required to resolve complex, intractable issues, both internal and external, requiring a fundamental rethinking of the business and culture. With this strategy, forward-thinking businesses can themselves embody the disruption in their environment. Adaptive innovation is a progressive strategy based on flexibility.

Paradoxical Thinking

The four resilience strategies could be seen as separate opposites, with an ‘either/or’ choice. However, organisations can live and thrive with paradox. Leveraging these tensions by employing ‘both/ and’ thinking is a critical aspect of organisational resilience¹. We explain the importance of tensions using the example of climbing. In organisational resilience, tension is also seen as a positive attribute.

Putting in place defensive strategies of control and responsiveness provides organisations with more confidence in their resilience. As a result, they are better placed to be progressive, take risks and shape the future.

Leveraging resilience tensions: a climbing example.

Put yourselves in the shoes of a climber wanting to undertake a dangerous ascent. You want to take a reasonable risk in order to explore and ‘push the boundaries’ and want to put in place a corresponding set of controls to make it as safe as reasonably possible. Prior to the climb, you enlist a trusted and experienced partner, check and double-check plans, ensure the weather forecast looks good for the ascent and gather all the appropriate gear. As you are about to start the climb, you double-check each other’s knot and belay device before starting the climb (controls). On the climb, awareness of the changing environment, effective communication and responsiveness become crucial (mindful action). Your climbing partner offers rope whenever you want to continue climbing and takes in slack whenever you are not moving – keeping the rope in tension. As you move up the face, you place protective gear into the rock, always more protection than you actually need (redundancy) just in case one fails. Should you fall, your climbing partner applies tension to the belay device holding the rope tight, and the protective gear would stop you from falling too far. Thus, the management of tension between controls and pushing the boundaries is essential to accomplish the task effectively and safely.

An example of how the tensions impact mindset and system design

To explain how the tensions impact our approach to organisational resilience, we use the example of an essential car journey to emphasise two different ways of looking at incidents.

A car journey is a high-risk activity involving a complex system with a range of components such as:

- Controls (the laws, fines, policing, speed cameras, road signs).

- Standards (e.g. driving test for driver competence, MOT test for vehicle roadworthiness).

- Technologies (e.g. cars, anti-lock brakes, airbags, seat belts).

- Rules (e.g. highway code, vehicle operating and maintenance manual).

- Human factors (e.g. attitude to risk, attention, care).

- Contextual conditions relating to the task (e.g. overcoming time pressure).

- Environment (e.g. coping with the icy road, distractions).

- Capabilities (e.g. familiarity with the location, expertise).

All of these system elements are critical for the successful completion of the journey. Imagine that an incident occurs, and the journey is disrupted (e.g. a mechanical failure or collision).

In Table 4, we show how people operating from the bottom two quadrants of the tensions model might explain this incident.

Table 4. Two contrasting ways of looking at incidents

| A failure of preventative control? | A failure of mindful action? |

| Initially, the system design was perfectly sound and could be controlled within a range of acceptable tolerance. | Initially, the system design was imperfect and prone to failure. |

| Layers of protection had been hard-wired into the system. Wherever possible, the system components had been automated. | Every day, operators (drivers) make up for holes in the system’s design by anticipating and adjusting to the environment’s changes. |

| The incident must have been the result of failed system components – a widget or probably human error. | The incident must have resulted from a temporary breakdown in the operator’s (driver’s) ability to adjust to their environment. |

| We must rectify or replace the technical problem and remove those culpable or train them to comply with standardised processes to regain control. | We must learn what it was about the situation (e.g. time pressure, distractions) that led to the incident. We can give operators (drivers) opportunities to encounter novel situations and problems to improve their ability to anticipate and absorb variations and surprises. |

| Updated and reviewed periodically (quarterly, annually). | Ongoing monitoring and review of the essential outcome. In some organisations, this involves feeding in live information to anticipate and prevent disruptions. |

Our point is to emphasise that there are divergent views on how to achieve resilience. A person with the perspective on the left (of the table) will perceive issues and make decisions very differently from a person with the perspective on the right. You may have people in your leadership team with both of these perspectives. Neither of these perspectives are right or wrong. In most organisations, different perspectives will coexist, often between different departments.

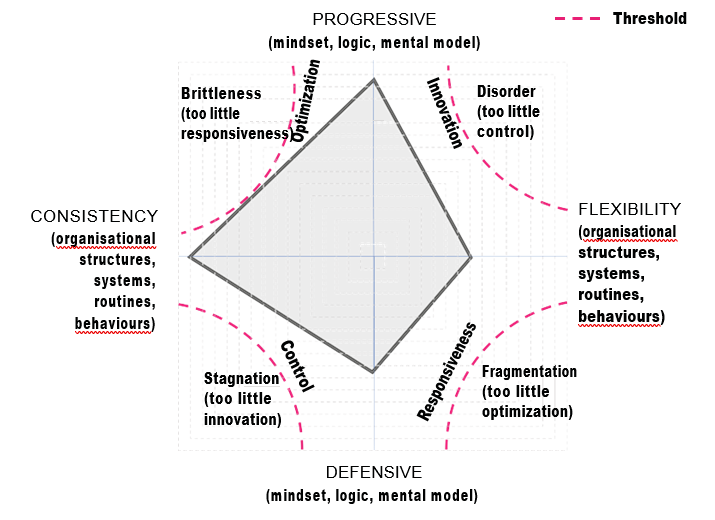

Every organisation has a uniquely balanced profile that is usually made up of some combination of all four core strategies (as shown in Figure 3).

One size doesn’t fit all. Instead, the overall organisational resilience approach will vary according to the nature of the organisation, its mission, and the environment and circumstances it faces. It is also likely to change over time as the strategy in the organisation itself evolves. As shown in figure 4 if the organisation extends one dimension (e.g. optimisation), there is usually a corresponding impact in the other dimensions through increased focus and investment.

An overemphasis on any of the resilience strategies can create blind spots and vulnerabilities and enhance the potential for disruption and crises:

- Stagnation: too much control with too little innovation can make essential outcomes static, stale, and uncompetitive, threatening the organisation’s

- Fragmentation: too much responsiveness with too little optimisation can be inefficient because of duplication of resources and Critical information can fall into the ‘cracks’ between functions enhancing the potential for incidents.

- Brittleness: too much optimisation with too little responsiveness can strip out slack or system The adaptive and responsive capacity necessary to contend with complex and dynamic environments can be inhibited.

- Disorder: too much innovation with too little control can heighten the risk of failure when innovation outstrips rules and regulations.

Using the tensions model to improve essential outcomes

For each EO identified in the section on understand outcomes, it is now possible to examine each EO and make choices and changes to enhance resilience based on the four resilience intervention choices and four outcomes of resilience – 4Rs: readiness, responsiveness, recovery and regeneration (see the section on measuring resilience for a discussion of the 4Rs). The choices include:

- Controls to increase readiness – g. add safeguards, add new plans or procedures, add codes of conduct, ensure compliance, find and fix errors, increase supervision/oversight/audit.

- Flexibility to increase responsiveness – g. add redundancy, adddiversity, create flexibility (by design) empower people by giving them the freedom and discretion to act, develop teamwork and communication.

- Innovation to increase regeneration – g. create safe spaces for experimentation, encourage informal networking, developing new capabilities, resources and ways of working, design thinking workshops.

- Optimisation to improve recovery – g. clarify existing roles and responsibilities, improve existing processes, reduce cost, improve monitoring, fix gaps in knowledge and skills.

Generating intervention options can be a creative process where teams generate ideas in sessions (e.g. brainstorming, worst possible idea). Participants gather with open minds to produce as many ideas as possible to address a problem statement in a facilitated, judgment-free environment.

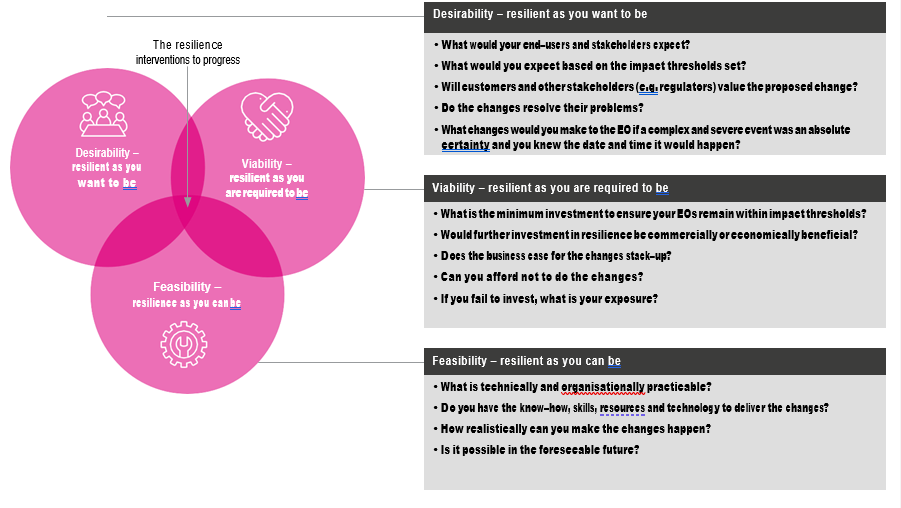

Desirability, Feasibility, Viability

In design thinking, innovations are progressed when three conditions are met: someone needs it (desirability), you can deliver it (feasibility), and it makes economic sense (viability). We have adapted this approach for resilience (Figure 4):

Prototyping

One of the best ways to gain insights into the resilience process and improve is to carry out prototyping. This method involves trialling an early and scaled-down version of the changes to the EO to reveal any problems with the design. One of our leaders explained that continuous experimentation was vital to their business. They view each of their hundreds of business units as laboratories in which “if we don’t have the answer, we make it up and test, but in a controlled way. Curiosity and fast failure are essential in a rapidly changing environment.”

Prototyping offers people the opportunity to bring their ideas to life and test the current design’s practicability. A sample of users can be asked what they think and feel about the changes, revealing new issues or areas for improvement. Prototyping can quickly identify whether or not the implemented changes have been successful. The results generated from prototyping can redefine the customer journey map and resilience blueprint established earlier. Prototyping can build a more robust understanding of the problems users may face when interacting with the EO.

6. Stress test thresholds

All of the organisations in our research undertake scenario testing.

Tests include failures within their control (e.g. IT system failures) and those outside of their control (e.g. cyber-attack or disruption to the power supply). Leaders said that they identify an appropriate range of adverse circumstances of varying nature, severity and duration relevant to its business.

The right team of people needs to come together to conduct the exercise, particularly those with individual responsibility for areas that are impacted and those responsible for the resources that provide contingency or recovery measures. Some leaders commented that scenarios need to include a broad range of stakeholders, including third party suppliers, customers or end- users too where appropriate. An external challenger in these scenarios is encouraged to address the issues of plausibility and groupthink.

All interviewees remarked that people quickly disengage from planning involving scenarios, such as a flood or terrorist incident, regardless of how plausible they are. The problem with working with a specific scenario, such as a pandemic, is that people cannot escape from their implicit assumptions about how likely it would be, which clouds judgements and, as one interviewee said, “is not a sound basis for making responsible decisions.” Another resilience leader suggested, “we had to stop playing hurricanes”.

Many of the organisations in our research have switched to scenarios based on disruption to its essential outcomes. The testing aims to assess their ability to remain within their defined impact thresholds.

The impact threshold-based approach is hazard agnostic, i.e. the cause of the impact is not labelled. Instead, it involves applying a series of ‘what if’ situations to the EOs. For example;

- What if X% of your employees, or key individuals or groups, cannot work for X days?

- What if your access to a service you rely on (e.g. electricity or water) is unavailable for X days?

- What if the supply of materials or goods you rely on is disrupted for X days?

- What if your buildings couldn’t be occupied for X days/weeks?

- What if several of the above impacts happen concurrently?

Each of the impact situations can be stretched to identify single points of failure, vulnerabilities and to help define the thresholds. Leaders argued that with the impact threshold approach, people have to assume that the event will happen and decide whether or not the EOs are compromised. This helps organisations focus on what is essential and how to deliver it when the inevitable disruption occurs.

Learn from experience

Organisations are tested every day by issues, near misses and incidents that are learning opportunities. Resilient organisations review their successes and failures, assess them systematically, and record the lessons in a form that employees find open and accessible.

Incidents not only cause harm, service loss, or emergency but also generate surprise and shock. These incidents can create a mismatch between people’s way of thinking (e.g. what is safe, acceptable, ethical, tolerable, standard?) and their environment. Therefore, recovering from an extreme event requires a “full cultural readjustment… of beliefs, norms, and precautions, making them compatible with the newly gained understanding of the world¹⁴.”

Many organisations are adept at gathering information but are markedly less effective in applying that insight into their practices. With many incidents, organisational learning often stops with the publication of ‘lessons learned’, overlooking ‘lessons applied’¹¹.

Without making changes in the way that work is done, only the potential for improvement exists.

People often overestimate their ability to have foreseen incidents (this is called hindsight bias). We then simplify our interpretation of what went wrong, narrowing it down and isolating the main causes (often the widget that broke or the person who messed up).

They tend to use their character or attributes (e.g. recklessness, driving ability) to explain the actions that contribute to an incident. They tend to focus on external situational factors outside of their control (fundamental attribution error). The detrimental effect of these cognitive biases on learning from experience is profound. The approach to incidents in some organisations can be a bit like the children’s game of whack-a-mole. It is a cycle of repeated efforts to find and fix problems and be frustrated by the problem reappearing in a slightly different form.

Leaders said that both structured or informal investigations need to focus on learning and reflection on an essential outcome’s operation. Reviews are often conducted after an incident or a near miss but can also be undertaken when things go right¹⁰. A prerequisite of a review is that everyone feels able to contribute without fear of blame or retribution. These types of review are about learning, not holding people to account.

Investigations are usually about who is to blame, who did what, who said what – often conducted by lawyers and forensics specialists, but these should not be confused with lessons to be learned reviews, which have a different dynamic as reflected in the statement ‘everyone feels able to contribute without fear’.

Modelling impacts (e.g. digital twin, cyber ranges)

A digital twin is essentially a replica of the essential outcome consisting of the multipurpose virtual environment, including people, processes, and technology to protect their strategic information, services, and assets. A digital twin can simulate an essential outcome’s performance, enabling ‘what if’ scenario planning. Modelling allows a company to explore choices and possible changes, including all the impacts, dependencies, and trade-offs. The approach has been used to analyse supply chain resilience for many years. It is gaining more attention due to technical and computational capabilities and advanced analytics. However, modelling doesn’t have to be too complex to achieve real benefits.

Think of a motorway collision analogy – we don’t necessarily need to model the events leading to a crash itself, or necessarily the steps to get the ambulance to the scene, clear the wreckage and reopen the lanes. Yet, it would be valuable to model the impact of the disruption on EOs, such as the impact on other road users trying to get to where they need to be. At this stage it is essential to link back to the earlier stages of the methodology. The resilience blueprint is a crucial tool that is used to provide an accurate understanding of how EOs are delivered and how alternatives, contingencies or other interventions could deliver EOs, within impact threshold. The five capitals impact scenarios could be used to test the what ifs? And to test the effect of assumptions made. As noted earlier, examining assumptions is more important than using scenarios related to a plausible cause of the event.

Testing assumptions, such as what happens if we close lanes of the motorway? What’s the impact on drivers? What’s are the likely effects of any interventions we would/ could make (e.g. communication to drivers not to use the motorway unless essential etc). We don’t need to be specific as to why two lanes are closed. Crucially, the modelling needs to focus on the use of alternates (e.g. diversion routes).

Like a digital twin, a cyber range is designed to mimic real-world scenarios in a virtual environment. These experiments are controlled, enabling users to determine the parameters an individual will experience. Cyber ranges have been used to help users detect and react to simulated cyberattacks, enabling them to test new technologies and enhance cybersecurity platforms. A simulation environment is created. A group known as the red team tries to exploit the vulnerabilities present in the system. In response, a group known as the blue team tries to defend the system and prevent attacks. Such an approach could be adopted for other incident types. Within a virtual environment, one team would try to manipulate weaknesses in the system. The other team would try to reinforce defences and make adjustments to minimise the impact. Again, the basic principles of a cyber range could be adopted without making the exercise too complicated. Some leaders warned that people could become so engrossed in the technology that they lose sight of the overarching aim, strengthening the resilience of the organisation’s essential outcomes.

New opportunities can also be modelled and measured within alternate scenarios of the future. This enables organisations to examine readiness to address changes and to test decisions and judgements about how to use resources. Modelling can also lead to examination of the effectiveness of networks of individuals and organisations to address change together. Using modelling and simulation a rounded view of the benefits of resilience may be obtained.

Modelling and simulation can examine strategic choices and transition paths to planned goals, such as zero carbon. These transitions can be broken down into phases indicating the uncertainty and volatility of each phase, and the resources likely to be needed to continue the transition effectively in the real world. It gives an opportunity to test longer-term possibilities by providing information about specific choices we should (or should not) make today (for example, those that might limit our options some years down the line).

7. Enable adaptive leadership

Leadership is critical for organisational resilience¹⁵. During COVID-19, senior leadership teams came together daily to share information and make essential decisions. COVID-19 shows us how quickly events can unfold. Decisions were made, and actions were taken every day (e.g. restricting travel, working from home, banning mass events and closing schools). Often these were criticised as costly over-reactions one day but were seen as ‘too little too late’ just a few days later. In a crisis, solutions can’t be objectively judged as right or wrong, just better or worse.

Continuous and widespread communication was also highlighted as a critical function of leadership. In the crisis, organisations mobilised a pre-existing ‘Gold Command’ crisis structure, comprised of executive team members. It should be noted that Human Resources and Corporate Communications played particularly prominent roles in most organisations COVID-19 response. An informal subgroup was also formed in many organisations to provide management support for the crisis under the Gold team’s direction. These groups were small multi-disciplinary teams (typically 8-12 people) who were empowered to address emerging issues.

Another key feature of COVID-19 in most organisations was the ‘work of leadership’ took on multiple directions, transcended formal hierarchies and involved multiple people. Regardless of the hierarchical position, many people enacted practices traditionally viewed as leadership behaviours or styles.

Rapidly changing circumstances require many people in organisations to undertake leadership practices, working collectively in the situation. Leaders told us about the achievements, people making changes to organisational practices, and developing novel resilience interventions.

Leaders described the three leadership outcomes described by Drath and colleagues¹⁶: direction, alignment and commitment (DAC). The DAC approach allows us to examine how people in the organisation produce direction, alignment, and commitment to resilience:

- Direction involves a shared agreement about the overall purpose, fundamental principles and aims and the perceived value of Board level and top management understanding and buy-in are essential to ensure organisation-wide participation in organisational resilience.

- Alignment refers to effective communication and the coordination of individuals and groups across the It includes the contributions of third parties and the collective action of multiple stakeholders towards the resilience effort. In organisational resilience programmes that have achieved alignment, resilience is embedded in planning, budgeting, performance management, and reward systems.

- Commitment – denotes the willingness of individuals to join the collective resilience In organisational resilience programmes that have produced commitment, people devote their time and energy to resilience. People are deeply committed to responding to new challenges and opportunities as they emerge and take, and feel, personal responsibility for resilience.

Resilience Reimagined: A new model for organisations

The seven practices form a new resilience methodology for organisations:

Building resilience is not straightforward as organisations vary in terms of purpose, strategy, and priorities. One size doesn’t fit all. A strictly standards based approach can lead to a narrow, box-ticking, inflexible system, which squeezes out professional judgement.

Instead, the overall organisational resilience approach will need to vary according to the nature of the organisation, its mission, and the environment and circumstances it faces. It is also likely to change over time as the strategy in the organisation itself evolves¹. Building resilience cannot be assumed to be a one-time effort. Resilience is a moving target, ever-changing in response to the changing requirements of the context in which the organisation works and the changing conditions it faces concerning its ultimate goals. In most cases, leadership must aim to produce a dynamic strategy for organisational resilience and continually iterate, redesign, recreate, and develop resilience.

The methodology (Figure 5) has been presented linearly, with each practice informing the next. Feedback loops must exist between each of the practices and rely upon open communication within multi-disciplinary teams. Leaders may choose to focus their efforts on a specific practice or practices. But, they should always be mindful of the implications on an adjacent practice in the model.

Several iterations may be required before leaders feel comfortable to move on. For example, stress testing thresholds either through everyday experiences or by introducing hazard agnostic ‘what if’ situations should inform the strategic choices regarding resilience interventions to consider, requiring further threshold stress testing.

Figure 5: Resilience methodology: seven practices for organisations

We offer two ways in which leaders can self-assess their current resilience and chart their journey to improvement.

Self-Assessment

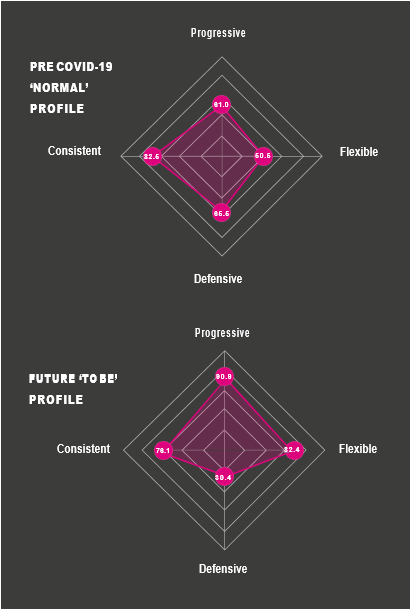

Using the strategic tensions model, an organisation can self-assess its unique profile that is usually made up of some combination of all four core resilience strategies¹. Figure 6 shows an organisation’s self- assessment of its profile based on a Strategic Tensions Assessment Tool (STAT) survey sent to a cross-section of over 100 employees. We asked;

- What was your organisation’s profile prior to COVID-19?

- What does the profile need to look like in the future?

The organisations perceived normal ‘as is’ profile is on the left, and its’ future ‘to be’ profile is shown on the right.

A STAT survey enables leaders to gain insight into how colleagues, employees, and stakeholders perceive organisational resilience – how it works now and how they imagine it working in the future. This understanding helps organisations to:

- surface differences of mindset and approach across individuals and groups (which can be profound).

- agree on a fit for purpose approach.

- surface and manage strategic tensions.

- identify blind spots and risk factors.

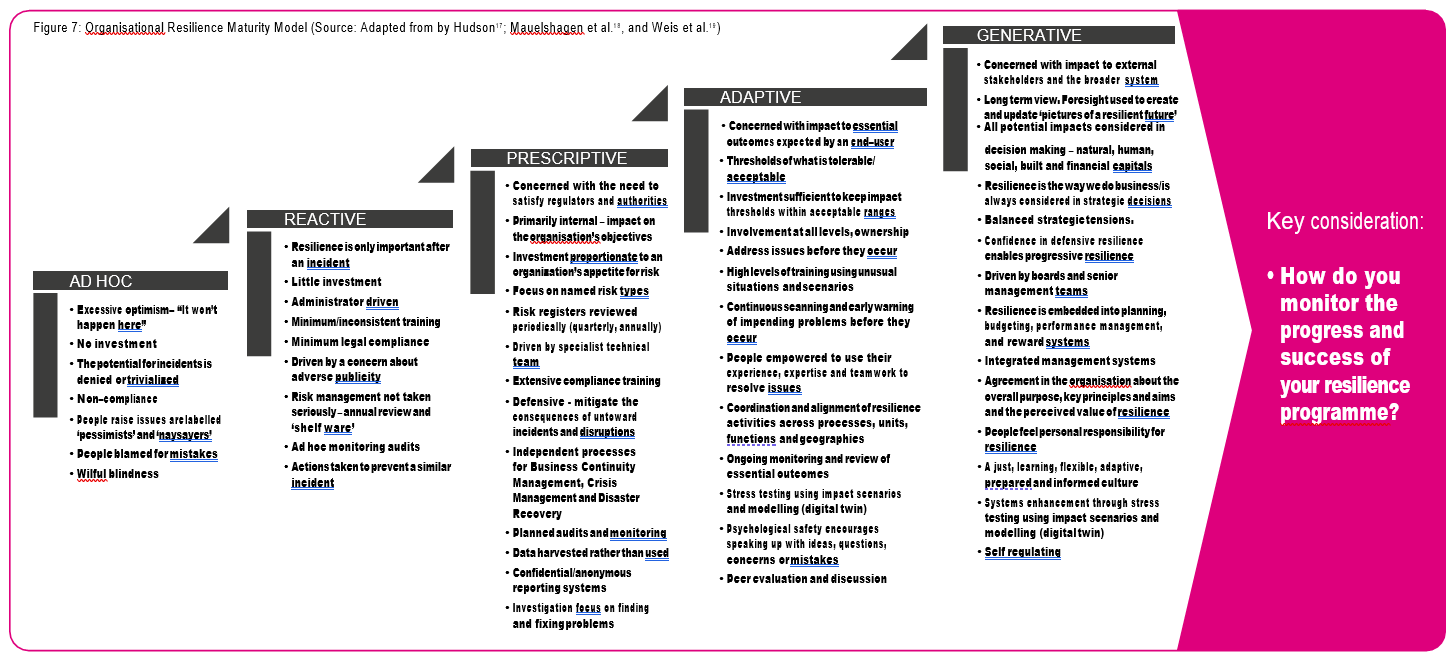

Resilience maturity model

We have developed a new maturity model (Figure 7) to provide a qualitative assessment of the transition towards a fully generative resilience approach. It is intentionally aspirational to create improvement opportunities around elements that underpin resilience. It is not designed to be a ‘one-time assessment’ but rather a scale to demonstrate change over time. The model builds on existing peer-reviewed research into maturity models in other disciplines and has been explicitly customised for resilience.

The maturity model contains detailed descriptions of five levels of increasing maturity and can be applied either at organisational or function or business unit level. The key considerations offered throughout this report can assist in determining what level of maturity is most appropriate. It provides the basis for a useful roadmap for the cultural transformation that is needed. The leadership team could also discuss areas for improvement and agree on those for progression. Inevitably there will be different views on the level of maturity based on differing perspectives and types of evidence. This is normal and to be expected. The most significant value comes from exploring the reasons behind such divergence of view and how best to evidence ratings.

Each maturity model element contains short descriptions of what may be expected at each stage. It is not a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ checklist, and in many areas, the answer may be ‘to some degree’. This points to areas where consistency needs to be improved. Therefore, there may be some good examples within the organisation to follow or poor examples where improvement may be targeted.

The maturity model is designed to stimulate discussions across the organisation and identify good practice and areas for improvement. The model may also help prioritise resources. Arguably, it is more critical that some organisations reach a higher state of maturity more rapidly than others. At the Board level, the maturity rating provides a dashboard of the organisation’s transition over time.

Measuring resilience: Towards evidence-based practice

Many organisations express the desire to measure resilience. The drive to justify the investment and monitor the success of resilience programmes is gaining urgency. However, organisational resilience is difficult to measure. Like personal health, resilience has two aspects: a negative aspect disclosed by incidents/illness (lagging indicators) and a positive aspect to do with the system’s intrinsic resistance to disruptive events/ fitness (leading indicators). Whereas incidents and illnesses convert easily into numbers, trends, and targets, the positive aspect is much harder to identify and measure.

How would you measure your health? Is there one measure or a series of measures that you would use? Like health, organisational resilience has ‘no stopping rule ‘. That is, how do you know that you have done enough to be truly healthy or resilient. Karl Weick regards resilience as a ‘dynamic non-event’. They are dynamic because moment-to-moment adjustments and compensations ensure processes perform as needed under a variety of conditions. They are non-events because resilient implies no adverse outcomes.

Conceptually, it is difficult to measure something unless we know precisely what has to be measured. Yet, existing definitions of organisational resilience do not readily facilitate this (see text box). It should be noted that many of these definitions conflate the outcomes of organisational resilience (thrive, survive, prosper) with the process of achieving it (prevent, adapt, absorb, respond, recover, learn). Few of these organisational resilience definitions address the importance of resilience in an organisation’s social contract across the five capitals and the outcomes that an organisation provides for society.

A selection of definitions of organisational resilience

“Resilient organisations thrive before, during and after adversity… a mindset of what if? And what next? Not just the next risk, but the next opportunity” (Deloitte).

“the ability of an organization to anticipate, prepare for, respond and adapt to incremental change and sudden disruptions in order to survive and prosper” (BS65000).

“the ability of firms and FMIs (financial market infrastructures) and the financial sector as a whole to prevent, adapt, respond to, recover and learn from operational disruption (Bank of England, PRA, FCA).

Organizational resilience is the ability of an organization to absorb and adapt in a changing environment to enable it to deliver its objectives and to survive and prosper (ISO 22316:2017).

Despite the challenges outlined above, we offer one way in which resilience could be evaluated.

Evaluating the 4Rs of Resilience: Readiness Responsiveness, Recovery and Regeneration.

We believe that there is potential to develop an approach for evaluating the 4Rs of resilience. Research, particularly the extensive work on high reliability organisations3, has revealed that resilient organisations differ from their peers due to:

- Better readiness (preventative control) – they can avoid or prevent more untoward incidents and disruptions than their peers.

Recent studies20 on resilience suggests three further dimensions:

- More responsiveness (mindful action) – they are flexible and better able to adapt their response, so the impact of disruption on their performance can be lower than their peers.

- Faster recovery (performance optimisation) – the speed of recovery of essential outcomes (not just assets) can be faster than their peers.

- Greater regeneration (adaptive innovation) – the extent of recovery can be greater than their peers (generative and transformational, not incremental change).