Partnering With Purpose

About this report

Published on: November 1, 2021

This report, prepared by Marsh McLennan for the National Preparedness Commission, examines the opportunities for stronger interactions between public and private sectors. Founded on extensive desk research and interviews with resilience experts in the UK and abroad, it offers ideas for further exploration in the context of a much-needed debate.

The PDF download provides additional layout and visual formatting.

Authors

Richard Smith-Bingham, Marsh McLennan

Executive Summary

It’s frequently acknowledged that preparedness for contingencies that threaten UK wellbeing and prosperity needs the participation of all sectors of society. The concerns are large, varied, complex, interconnected, and far-reaching. In turn, resilience efforts need to be multifaceted, adaptive, and widely owned.

The private sector can, should, and is keen to contribute in many ways. Companies have much to offer by way of finance, physical assets, workforce, capabilities, and innovation. Many corporate leaders recognise the value of both resilient business ecosystems and more general societal commitments. The right conditions can enable them to align commercial imperatives with larger national ambitions.

The experience of recent crises suggests that existing national resilience arrangements fall short of what is required for current and future shocks. Sustained supply-chain challenges, extreme weather events, large-scale cyber-attacks, energy crises of different kinds, and a still- evolving COVID-19 virus all argue for efforts to be increased and made more supple. Insufficient cohesion around mitigation measures and contingency plans, as well as the failure to anticipate possible cascading effects, impede the best use and co-ordination of different capabilities across public and private sectors.

Reframing the goals of national resilience and fostering debate about sectoral responsibilities would create a greater unity of purpose. A tripartite vision might focus on 1) reducing broadly defined societal vulnerabilities, 2) maintaining the reliability of critical ecosystems, and 3) securing the UK’s long-term strategic imperatives. Against that backdrop and the risk outlook, government and the private sector should explore how far to go – separately and in collaboration – to enhance risk mitigation and crisis preparedness. Maximal resilience may not always be desirable.

Underpinning cross-sectoral interactions with the right ‘terms and conditions’ is fundamental to securing the best results. More creative, equitable approaches to risk sharing should be nurtured where changing risks severely compromise the commercial business case for investment and action. Regulatory regimes should look harder at systemically important sub-sectors, make resilience a more central tenet of their agenda, expand the use of stress testing, and tighten enforcement. New data-sharing provisions should reduce barriers to sharing (where appropriate) and support decision-making by better integrating open source, public, and private data. Government emergency measures that flex standard procedures should be deployed in ways that enable rather than inhibit private-sector contingency planning.

More generally, ensuring the private sector has a real seat at the table for resilience ideation and implementation would help reduce stovepiping tendencies within government and enhance traction for solutions across the economy.

The new national resilience strategy being prepared by government should stimulate and test new approaches that will position the UK well for the future. Numerous opportunities exist for public and private sectors to interact to greater effect, and much can be learned from initiatives in place already — in the UK and abroad. To take forward the selection identified in this report, government will need to play director, client, stimulator, facilitator, and cheerleader.

In ‘director’ mode, government could review the extent and deployment of existing legislative and regulatory powers. Key areas for examination include mandates for the production and stockpiling of critical goods prior to a crisis, requisition and production directives in a time of crisis, and enhanced powers of intervention to mitigate the potentially systemic impacts of large-scale cyber-attacks.

As ‘client’, government could further influence private-sector behaviour in line with new priorities. Key opportunities relate to adjusting contracting requirements to set resilience expectations of suppliers, creating a new suite of contingent contracts and procurement guidelines that could be drawn on in a crisis, and establishing a technology innovation fund focused on key resilience vulnerabilities.

As a ‘stimulator’ of markets, government could more strongly catalyse or expand novel solutions. Opportunities include cultivating an open research ecosystem where technology, innovation, and data can be combined in a pre-competitive environment; developing a multi-peril insurance scheme for catastrophes; building a cyber-risk pool that

Might focus on infrastructure loss events and/or small and medium- sized enterprises; and expanding the deployment of resilience and adaptation bonds.

As a ‘facilitator’ of innovation, government could enhance the integration of data and analytical capabilities. In particular, it could clarify or adapt legal guidance on data sharing to alleviate uncertainties; provide researchers from all sectors with access to a data sandbox and complex analysis platform; ensure the flow of real-time data from diverse sources into the new National Situation Centre; enable the better stress testing of critical national infrastructure assets and supply chains against major contingencies; and encourage relevant private-sector businesses — particularly CNI operators — to participate in cross-sector crisis exercises.

In ‘cheerleading’ mode, government could help promote resilience initiatives developed within the private sector. Measures to be encouraged might include the inclusion of metrics on asset resilience and risk governance in outputs from rating agencies and investment data providers; the creation of industry-based crisis codes of conduct that would help establish expectations as to reasonable behaviour by firms during contingencies; and efforts by companies to enhance the resilience capabilities of their employees.

This report, prepared by Marsh McLennan for the National Preparedness Commission, examines the opportunities for stronger interactions between public and private sectors. Founded on extensive desk research and interviews with resilience experts in the UK and abroad, it offers ideas for further exploration in the context of a much-needed debate.

Introduction

This is a pivotal moment for re-energising resilience efforts at the national level. With the severe, concurrent tests of the COVID-19 pandemic and reverberations from the UK’s departure from the European Union by no means over, the government’s Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy is already pointing us to a kaleidoscope of strategic challenges that policymakers and the country at large will need to navigate in the next decade.₁

In laying out a strategic framework for action, Global Britain in a Competitive Age suggests that our collective approach to addressing possible setbacks and catastrophes should emulate the problematic trends and contingencies the nation might face. In other words, if risks and threats are interdependent by nature with transboundary impacts, it’s vital that decision-makers and resilience policies are joined up across government departments. If exigencies have complex causes and spill-over effects, we must both explore upstream solutions and expect to manage downstream consequences. If we give credence to the possibility of high-impact risk scenarios, we must prepare, invest, and regulate in good time and at scale. If we anticipate crises that might speedily change shape, our capabilities will need to be multifaceted and our deployment of them supple. If the issues are cross-border in nature, it’s incumbent on us to work closely with allies and partners and, on some issues, with regimes that do not share our values or our goals.

While these conditions demand more ambitious risk assessments and more astute decision-making, they also require the contribution and collaboration of different sectors of society. Most of the possible emergencies on the horizon cannot be solved or mitigated by government alone. Not only is it undesirable for responsibility to be so concentrated, it also represents an opportunity lost. But galvanising and truly mobilising a ‘whole-of-society’ response (to use a well-worn phrase in national resilience circles) is more easily said than achieved. All too often there is a chasm between assumptions and reality, plans and execution — sometimes due to unforeseen eventualities but more often due to underwhelming levels of alignment and traction.

While acknowledging the need for a holistic view involving all sectors, this report, prepared by Marsh McLennan for the National Preparedness Commission, examines the opportunities for stronger interactions between public and private sectors. Founded on extensive desk research and interviews with resilience experts in the UK and abroad, it offers ideas for further exploration in the context of a much-needed debate, rather than landing on fixed conclusions and firm recommendations.

To be manageable, the project has had to make choices about scope. The paper therefore targets preparedness for and resilience to risks and possible crises that are of national concern due to their intensity, persistence, or likely evolution, rather than more routine problems.₂ Within that context, it speaks more to civil contingencies than to purely economic or financial disasters or, indeed, to security challenges such as terrorism, the protection of sensitive technologies, or military confrontation. It does not find space to consider industries that need to be nurtured or vital systems, such as healthcare, that are highly stretched. It is conscious of, without being explicit about, a shifting global environment — geopolitical, climate-related, technological — and the transformational national policy agenda that this demands. It looks more closely at central government capabilities and the firms that might provide the most strategic impact than at local government and the broader economy.

Furthermore, it focuses more on general capabilities and interactions that might be leveraged and adapted in a range of circumstances rather than specific strategies for multiple specific challenges — such as improving food security, governing the deployment of advanced technologies, or adapting to individual extreme weather perils. In passing each fork in the road, we have been very aware of alternative conceptual frames and the valuable work to be done down each path not taken.

The report contains two key sections and a large appendix. Section One briefly summarises key systemic shortcomings in public-private interactions experienced in the context of particular crises before exploring four areas that would help achieve greater alignment and traction. Section Two introduces five roles for government in galvanising the private sector in pursuit of national resilience and presents a collection of opportunities or initiatives that would provide lasting value. These ideas are explored in more detail in an Appendix, which, for each opportunity, sets out the context, analogue schemes already in place, and key considerations.

Framing the Way Ahead

Recent crises illustrate both the need and the scope for refreshing how public and private sectors can work together for national resilience. More conscious alignment at all levels of the relationship will make for more lasting traction.

Shortcomings and Disconnects

High levels of national resilience will be essential as government and the nation at large work to:

- Facilitate a smooth economic recovery from the pandemic, transitioning from crisis support to sustainable and equitable growth

- Counter pervasive, persistent, and evolving risks (e.g. sophisticated cyber-attacks) that are hard to control

- Deliver on bold economy-wide transformational agenda (e.g. decarbonisation and digitalisation) that need high levels of mobilisation

- Reset international relations with a view to deeper trade and investment arrangements and the achievement of stronger global influence.

Addressing each one of these imperatives in isolation is hard enough. Foreseeing additional problems where they rub up against each other requires creative vigilance; needing to resolve simultaneous crises diverts effort, slows progress, and reduces public trust.

Exhibit 1 (on the next page) gives a fuller picture of national-level risks and threats. But a brief look at four current crises — each with different dynamics — is perhaps a more tangible means of highlighting areas for resilience improvement.

First, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused colossal damage to households and the economy. The health system has struggled to cope, many businesses have been severely impaired or folded, and economic inequalities have deepened.₃ These outcomes raise questions about the UK’s preparedness for infectious disease emergencies, the quality of crisis response decision-making and capabilities, and the allocation of investment for a speedy recovery.₄

Second, supply challenges of various kinds have come hot on the heels of each other since the beginning of 2020. Collectively and cumulatively, the effects of COVID-19, the UK’s departure from the European Union, the blocking of the Suez Canal by a container ship, the reduced availability across the world of ships and aircraft, the gas price crisis, and fuel shortages continue to reverberate through the economy in multiple ways.₅ These contingencies raise questions about the quality of regulatory preparedness and scrutiny, the shortcomings of business supply-chain models, and the effort given to contingency planning (especially regarding the continuity of critical functions).

Third, cyber-risk has become yet more pervasive and expensive. Ransomware attacks have surged, internet-based economic crime has soared, foreign state-related incursions continue to be persistent and complex, and mis/disinformation campaigns continue.₆ Mindful of the prospect of a more catastrophic cyber event, these trends raise questions about the strength of the UK’s cybersecurity ecosystem, the level of organisational attention to cyber-risk and workforce training, and the extent of insurance-based protection.

Fourth, climate-related challenges are intensifying with time windows for response shortening. Extreme weather events take place with increasing regularity, long-term changes are eroding the reliability of physical defences and the continued availability of natural resources, and decarbonising the economy has a long way to go.₇ These developments raise questions about the protection of communities exposed to such disasters, the level and speed of investment in long- term adaptation measures, and the strength of policy and industrial measures to secure changes in all sectors that ensures the UK meet net-zero commitments in an orderly manner.₈

Exhibit 1: A taxonomy of national-level risks and threats

| acute/fast-onset | Chronic/steady-state/cyclical | slow-burn escalation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malicious human action |

|

|

|

| human induced/accident |

|

|

|

| natural hazard |

|

|

|

Source: Marsh McLennan Advantage. (2020, April). Building national resilience.

Sharpening Alignment and Traction

To strengthen interactions between public and private sectors it is valuable to explore challenges and opportunities in four areas: vision and goals, roles and responsibilities, terms and conditions, and relationships and protocols.

2.1. Reframe the vision and goals

Without a broad cross-sectoral appreciation of the need, attempts to strengthen national resilience may founder. After all, in times of ‘peace’ the cost of resilience is keenly felt — by both government and companies alike — while the value is all too often hidden. Resilience should be reframed not just as countering a negative (risk) but as an ambition that is accretive to prosperity and wellbeing for both individual organisations and the UK as a whole. Better preparedness for exogenous surprises makes for lower performance volatility, shallower damage from shock events, and greater government policy stability. All in all, a better environment in which to plan and invest, where public- and private-sector leaders can deploy capital more safely to the missions that will deliver the strongest social and economic returns.

Framing the national endeavour in terms of three distinct goals (see Exhibit 2) helps signal both obligations and opportunities for public- and private-sector actors and thus how they might interact.

Exhibit 2: goals for national resilience

01 – Reducing broadly defined societal vulnerabilities

- Reducing broadly defined societal vulnerabilities means lessening the impact of potential disasters on communities across the UK and spurring faster, more equitable recovery from them. This is achieved by enhancing the preparedness of individuals, communities, and businesses for both sudden-onset crises and also slow-burn, but inexorable, situational transformations. (Climate change and cyber threats might fit under both categories.) Principally, it requires timely investment (centralised and decentralised) in ‘structural’ resilience, a risk culture that is watchful and supportive, and an ability (physical, organisational, or financial) to absorb shock events when they occur.

02 – Maintaining the reliability of critical ecosystems

- Maintaining the reliability of critical ecosystems means ensuring the continuity of critical functions, flows, and services on which economic flows and societal wellbeing are dependent, with a particular emphasis on the economic infrastructure (such as energy, transportation, telecommunication, and banks) and the societal infrastructure (such as hospitals, schools, and government operations) that underpin them. Some of these assets and systems require large-scale investment to future-proof them against erosion and collapse (in the near or long term); many are high-profile targets of malicious attacks, not least for the cascading challenges that might ensue. Among other things, this agenda requires a deeper understanding of dependencies both within and between infrastructure systems, including the supply chains that serve them, along with continual operational upgrades and long-term resilience programmes.

03 – Securing the UK’s long-term strategic imperatives

- Securing the UK’s long-term strategic imperatives means developing the platforms, especially in emerging or fast-evolving fields, that can help the UK and its citizens enjoy freedom, security, and prosperity in the decades ahead and enable its businesses to be competitive both at home and abroad. This is achieved through nurturing innovations in key technologies and their application, building new markets, and driving through sectoral transformations in a determined manner. Not only does this require vision and pump-priming investment in line with clear goals, it also requires consistent commitment and regulatory foresight to forestall negative outcomes and encourage desirable forms of collaboration.

Pursuit of these goals surfaces perennial strategic challenges where public-private interactions need to align with greater unity of purpose. First, how to balance the needs of different time horizons. While existing infrastructure and related ecosystems may need immediate remedial action, delayed investment in longer-term transformations often results in more volatile performance, greater project complexity, truncated timescales, and higher costs for future generations. Second, how to balance effort across different phases of the resilience life cycle. Much is made of the difficulty of anticipating situational specifics, but even agile crisis response mechanisms and aggressive recovery programmes are likely to be inadequate if pre-emptive mitigation opportunities have been spurned. Third, how to balance different agenda. Addressing most risks of national concern presents unavoidable strategic conflicts between economic growth, societal wellbeing, environmental protection, and national security imperatives. And, fourth, how to balance individual freedoms and collective resilience in the context of a liberal and market democracy, especially at a time of significant societal polarisation. Trust — in both government and the private sector — is critical for lasting impact.

2.2. Refresh roles and responsibilities

Pursuit of the goals presented above opens an array of questions about the roles and responsibilities of government and the private sector, and how they inform both separate and collective action.

Conscious of the risk landscape, where should government step up its commitments based on its unique positioning? Mindful of market failures, where does it need to play a bolder role to mandate and regulate, nurture and facilitate the activities of others? And where, wary of growing contingent liabilities and the encouragement of moral hazard, ought it to back away and simply let market forces suffice? It goes without saying that government interactions with the private sector for resilience ends are not purely framed by regulatory obligation and the use of fiat powers in an emergency. A far more extensive range of collaborative endeavour includes investment stimuli, bailouts, joint research and development agenda, suasion, and celebration that leverage the self-interest and goodwill of the market.

Through a risk lens, the case for greater government intervention lies in those areas where momentum across the country on resilience to priority risks is insufficient (e.g. climate change); it is also valid where catastrophe is in the offing (e.g. pandemic). Through a national resilience lens, intervention is called for where there may be a mismatch between the financial or operational risk appetite of individual organisations that have systemic influence on the risk landscape and the tolerances of the broader economy that depends on them (e.g. utility supply outages); it is also valid where market behaviours skew actions that are either unfair to some parties (e.g. smaller companies) or result in other risks being avoidably exacerbated via cascading effects. More fully analysing existing resilience arrangements against these criteria may shed light on blind spots and opportunities.

Questions can also be asked of the private sector about where corporate responsibilities for resilience begin and end — acknowledging the very different capabilities of FTSE 100 titans and small enterprises. While many firms would do well to better anticipate extreme scenarios and more thoroughly bake resilience into their commercial endeavours and core operations, how far ought they to go in analysing their dependencies and then taking steps to influence supply chains, their workforce, and their customers? Indeed, to what extent should larger companies take on a more overt role in supporting systemic or societal resilience, and how can smaller, nimbler firms better contribute specific expertise?

Beyond regulatory obligation and the use of fiat powers, government interactions with the private sector should make better use of stimulation, suasion, facilitation, and celebration that leverage the self-interest and goodwill of the market.

Recent years have seen corporate interest in these questions grow in three ways.

First, greater global uncertainty had already elevated board and executive team scrutiny of macro-level forces that could destabilise operations and strategic positioning; nonetheless, the pandemic spurred much fresh examination as to what constitutes organisational resilience and how that can best be achieved both within a crisis and in advance.₉ Moreover, the COVID-19 experience has prompted firms to take a fresh look at risks in seldom-examined parts of their risk registers, explore more extreme risk scenarios, and recognise the likely need to grapple with concurrent crises.

Second, many companies have become more sensitive to their societal commitments. The pandemic amplified workforce wellbeing programmes, which increasingly recognised that employee resilience doesn’t stop at the office foyer or the factory gate. At the same time, companies large and small deepened their engagement with local communities and others in their ecosystem.₁₀ This reflects pre-pandemic momentum within many corporations to embrace a responsible capitalism mentality — foregrounding a commitment to all stakeholders, blending profit and purpose for sustainable growth.₁₁ Indeed, customers, employees, and investors are holding companies to an ever higher bar not only regarding their ESG (environmental, social, and governance) ambitions but also to their actual performance in pursuing them.₁₂

Third, an increasing number of companies are seeking a more active role in addressing large-scale public policy challenges that affect their business but can’t be resolved by government alone.₁₃ There is steady evidence of growing non-competitive alignment and cooperation between companies and with government (national and local) on cross-cutting challenges such as cyber-risk, climate change, artificial intelligence, diversity and inclusion, and the circular economy.₁₄ Such collaboration on societal issues is endorsed by nearly four-fifths of the public, according to one poll, with three-fifths holding the view that business leaders should step in and take the lead when government has not found the right way ahead.₁₅ A similar proportion of those in the workforce professes to choose their employer based on that employer’s values and beliefs, and elects to leave or avoid organisations that have an incompatible stance on social issues or that fail to address moral imperatives.₁₆

2.3. Revisit terms and conditions

Without the right small print, engagement with laudable goals and well- aligned responsibilities will likely wither over time. Three sticking points in particular would benefit from fresh thinking: who bears the risk and cost, standards and regulation, and data sharing (see Exhibit 3).

risk and cost allocation. Government understandably wants to lever in private capital and shed risk from its balance sheet to manage the overall burden on the public purse. While accepting that commercial returns are seldom risk free, the private sector understandably wants to be compensated for risks it is asked to assume that go beyond those that are justified by a commercial business case. Examples of such compensation include co-investment (infrastructure), offtake agreements (power producers), liability backstops (insurance sector), and indemnity agreements (COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers due to limited testing and emergency authorisation procedures). Normal accommodations on these issues can reach a breaking point when the risks get manifestly larger, government seeks to pass on more risk due to stretched fiscal positions, and the private sector has alternative opportunities for deploying capital.

More transparent, analysis-led discussions about risk between public and private sectors could lead more easily to equitable, creative solutions at a time of significant situational change and where the costs of inaction could leave the nation more exposed to physical and economic disaster.₁₇ Not only should these address the pricing of risk — and not just with respect to the insurance sector — they should also explore the range of fiscal and market solutions (including reserve funds, stabilisation funds, risk pools, catastrophe bonds, corporate levies, and borrowing) that might mitigate fallout in the event of crisis.₁₈

regulation. Few would dispute the need for directive frameworks (legislation, regulation, standards); the question is more whether they are sufficiently responsive to evolving circumstances and succeed in driving the right outcomes. Indeed, contrary to the precautionary principle that governs much scientific and medical agenda, in many other areas legislation for resilience (broadly defined) can be belated and backward- looking rather than well-attuned to future risks, market contexts, and solutions. Hard as it can sometimes be, greater efforts might be deployed to anticipate possible risk and sectoral developments to future-proof legislation more effectively.

Exhibit 3: resilience levers meriting revision

Risk and cost allocationRegulation

Data and intelligence sharing

Noting that the powers of oversight bodies differ significantly between sectors, regulation can struggle in three ways. First, a focus on holding individual asset owners accountable can make it hard to take a truly systemic view, especially when there are key interfaces and dependencies beyond the assets being regulated and where the whole system itself (e.g. energy, banking, and digital) is evolving apace. Second, it is hard to balance competing priorities at the same time (e.g. housing needs vs. construction on flood plains, expansion of capabilities and services vs. unwelcome side effects in the digital realm, consumer prices vs. long-term infrastructure functionality in the water sector, international competitiveness vs. national system stability in the financial sector). And third, enforcement is not always easy given difficulties in reliably assessing or verifying institutional performance with limited resources and also where penalties offer limited deterrence relative to the gains that might be achieved.

By way of developing arrangements that are more fit for purpose, several developments could be pursued.

It would be useful to review whether there are systemically important sub-sectors and firms that ought to experience greater oversight. These might include ‘hidden’ assets, such as parts of digital or technological ecosystems that are growing in importance or leading firms in niche industries whose operations supply other sectors. Alternatively, it might include growing segments of certain sectors (e.g. shadow banking or utility supply services) where the plausible near-simultaneous failure of several providers would have far-reaching consequences. The burden of expanded oversight might be mitigated by tiering expectations according to the size of the business, as in the banking sector. Indeed, while some regulatorymprovisions need to be the same for all, it’s important to ensure that regimes enable small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), not just large firms, to thrive. Recently proposed new powers for the Competition and Markets Authority ought to help in this regard.₁₉

There is merit in making resilience a more central tenet of regulatory regimes for which it currently seems an ancillary interest. Where the chief goal, as for many utility regulators, is to protect the pockets of present- day consumers based on an expectation of operational resilience, it can be hard to develop and implement cost-effective investment plans that anticipate both near- and long-term contingencies. Against this backdrop, it would be useful to expand stress testing of different types (strategic, financial, operational) across different critical infrastructure sectors as a matter of routine. Moreover, stronger cross-sector regulatory hubs — such as the UK Regulators Network and the Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum — could sharpen debate and help reconcile differing agenda of bodies with separate statutory powers.₂₀ Indeed, it has been frequently observed in the last few years that sectoral, industrial and corporate evolution has blurred many traditional boundaries, presenting problems for regulators with dated, siloed authorities.₂₁

Finally, there may be opportunities to be more imaginative in the deployment of regulation. By way of example, perhaps incentives and sanctions could be more effectively combined in one regime. Widening the differential between stronger and weaker resilience performance might sharpen engagement and reduce attempts at free riding. Additionally, there is often scope to make better use of suasion on strategic issues where further industry leadership is needed — for example, through industry- initiated standards or pressure on systemically-important firms.₂₂

Data and intelligence sharing. Commercial confidentiality and national security sensitivities are often cited in the context of interaction or cooperation failures between public and private sectors. While intellectual property, commercial data, personal data, and a significant amount of government intelligence unquestionably need to be protected and not shared for a variety of reasons, significant scope exists for better data sharing under the right circumstances.₂₃ Where this works well it can be a powerful tool. Government’s greater openness regarding threats from Russia (viz. regular cyber-attack attributions) has helped sharpen the nation’s awareness about the disruptive agenda of foreign powers. In a very different way, the Financial Sector Cyber Collaboration Centre (FSCCC), in partnership with the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), usefully aggregates and shares information on incidents from across the sector to assist attack responses.₂₄

Nonetheless, data is all too often subject to institutional protective instincts and structural (regulatory or policy-driven) barriers. While sometimes government and companies have come together well (e.g. to address food supply concerns during the first COVID-19 lockdown), at other times intelligence and perspectives on impending challenges have not been fully shared or put to best use in good time. Data sharing with and between critical industry operators can be patchy and, where it is not fully comparable, it can be hard to obtain an industry-wide or cross-sectoral view on resilience. Appreciating their data-based contribution to the COVID-19 response and other agenda, there is undoubtedly more that the big technology firms can do to help mitigate mis/disinformation, internet harms, cyber-attacks, and criminal activity.₂₅ For its part, government’s predisposition to classify documents and intelligence that might have widespread value has been frequently questioned.₂₆

Among opportunities for change, government could take greater advantage of the growing grey zone between open source, public, and private data, and build that into its analytics; it could also explore new approaches for real- time data sharing that can support decision-making. Honing conventions (such as temporary suspensions of the Competition Act) that enable private-sector companies to contribute data to collaborative endeavours that would benefit their own resilience as well as that of others would also be desirable.₂₇ Following the example of Australia regarding cyber-attacks, government might also seek powers to compel critical infrastructure operators to hand over data in the event of a clear breach of resilience.₂₈ In addition, sharing risk scenarios that are not sensitive on national security grounds would be a helpful and credible starting point for companies that have limited risk resources but which would like to examine their ability to cope with different contingencies.

Government could seek to harness the grey zone between open, public, and private data, explore new approaches for real-time data sharing, endorse greater private-sector data collaboration, and compel post-breach data disclosures.

2.4. Reinvigorate relationships and protocols

To adapt an old adage: Frameworks are good, but behaviours prevail. If the pursuit of national resilience is a ‘whole-of-society’ effort with many independently moving parts, how public and private sectors engage with each other — within and outside formal initiatives — will greatly influence outcomes.

Respecting national security considerations, the private sector could participate more deeply in strategic national-level risk and resilience discussions — not only with respect to single-sector or single-issue analyses with narrowly defined purposes (many of which happen already) but also in more broad-based forums in which experts and practitioners from different sectors might contribute to and challenge government thinking on cross-cutting agenda on a regular basis.₂₉ Done well, not only would this enhance situational awareness and possibly under-appreciated spill-over effects, it might also counter stovepiping tendencies within government and lead to greater innovation and broader traction with emerging solutions.₃₀

Moreover, a collaborative approach to addressing strategic problems and implementing solutions is often most productive — even where fiat is the most appropriate mode of government intervention. Where the private sector lacks a real seat at the table, suboptimal outcomes can result: compliance alone is rarely the true goal and inertia can make generally good initiatives fail.

Stronger, more dynamic interactions between public and private sectors in a crisis are also vital. At times of heightened concern, it is entirely sensible that government should adapt priorities, policies, and operating practices: the ability to tighten or ease regulations in an emergency can mitigate escalating problems or act as a shock absorber. By way of example, the first 15 months of the pandemic saw major encumbrances on operations and working practices in all sectors. At the same time, other impositions were eased: various categories of enterprise were offered business rates relief, government procurement protocols were relaxed, and barriers to collaborative action between firms in certain competitive environments were eased.₃₁

Under such circumstances (and each new crisis brings its own exigencies), rigidity is undoubtedly an enemy of resilience. At the same time, consistent signalling and communication from government builds trust and enables business to take (often bold) decisions on contingency plans with reasonable confidence in their appropriateness. While complex, fast- moving situations mean that government policy may well evolve, clearly stated priorities and decision thresholds enable companies to get a head start in anticipating future policy scenarios and the implications for their business.₃₂ Moreover, the application of flexibility needs to be ethical and transparent, justified not only by the perceived benefits but also by a view on the possible unintended consequences, and governed by clear procedures for reverting to ‘peacetime’ practices in due course.

Opportunities

Multiple opportunities exist to align agenda and capabilities for national resilience. How each might shape up would depend on the role government is prepared to adopt to catalyse private-sector participation.

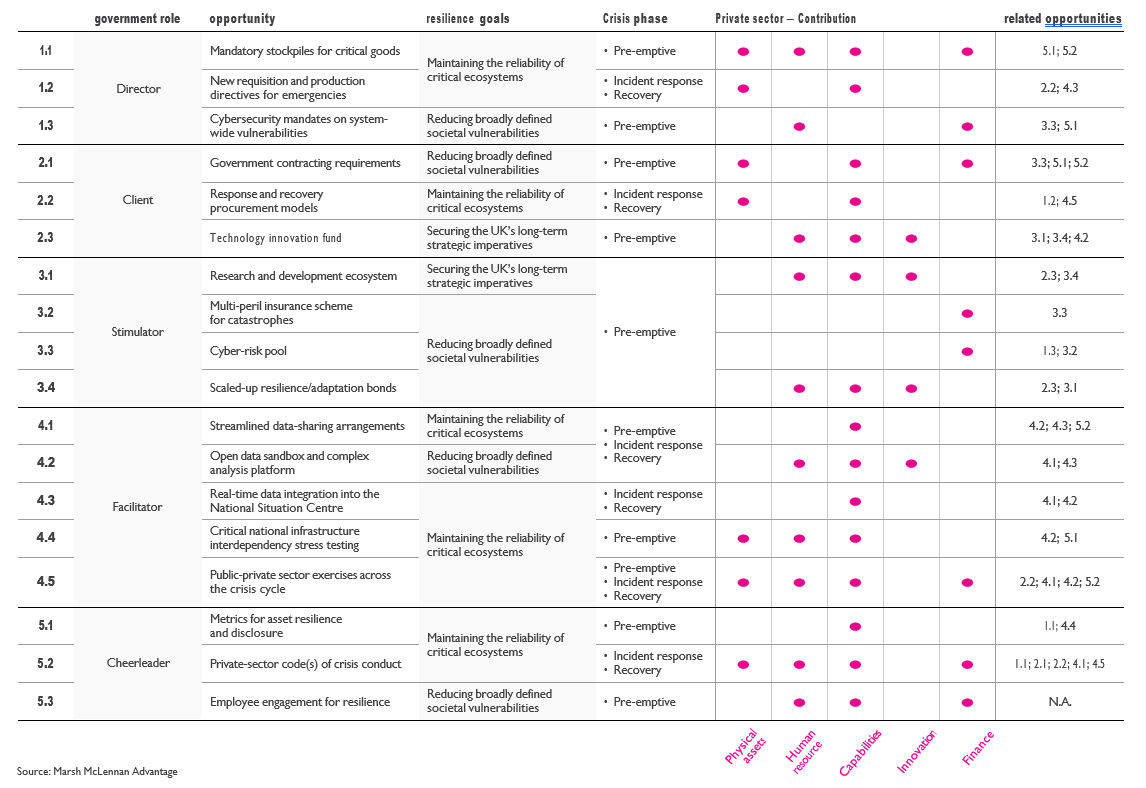

This final section sets out a collection of possible initiatives that emerge from the thinking in the previous section. They are not recommendations, merely food for thought. The organising principle is the role that government might play (see Exhibit 4), from being highly directive at one end of the spectrum to hands-off encouragement at the other. Some ideas could also fit in a different category, if alternative levers were chosen.

Most of the opportunities presented are not peril-specific; they concern themselves more with the enhancement of fungible capabilities that can help responsible parties anticipate and respond to different risks and crises. Their genesis lies in wondering how private-sector resources — finance, physical assets, workforce, capabilities, and innovation — might be leveraged or nurtured for national resilience either in combination with government capabilities or in combination with each other in a setting that needs to be made available by government. In each case, efforts have been made to articulate what drives the need, how initiatives benefit both national resilience and private-sector participants, and, where applicable, how implementation would expand or reorient existing endeavours in the same or adjacent spaces.

This chapter just presents the essence and value of each opportunity. An appendix sets out — for each — further details on context and rationale; analogue interventions in the UK and abroad; and key considerations that would need to be addressed in further exploration. Another appendix comprises a table that schematises the suite of opportunities and how they interconnect.

Exhibit 4: opportunities and the role of government

Director

Requiring and enforcing practices using legislative powers and regulatory tools

- Mandatory stockpiles for critical goods

- New requisition and production directives

- Stronger cybersecurity mandates

Client

Building traction for corporate standards and efforts as a large procurer of goods and services

- Government contracting requirements

- Emergency procurement models

- Technology innovation fund for resilience

Stimulator

Incentivising market creation or growth in key areas to shape corporate endeavour and innovation

- Research and development ecosystem

- Multi-peril insurance scheme

- Cyber-risk pool

- Scaled-up resilience/adaptation bonds

Facilitator

Streamlining processes and convening different parties to enable collective action

- Streamlined data-sharing arrangements

- Open data sandbox and analysis platform

- Real-time data for the National Situation Centre

- Critical national infrastructure stress testing

- Public-private sector exercises

Cheerleader

Encouraging behaviours from other sectors through awareness raising and policy adjustments

- Metrics for asset resilience and disclosure

- Private-sector code(s) of crisis conduct

- Employee engagement for resilience

Source: Marsh McLennan Advantage

1. Government Directing Private-Sector Priorities

Opportunities exist to implement or deploy more robust arrangements where deficiencies in critical outcomes are most manifest. Expanded government powers would be valuable where enforcement is challenging, flexibility is required to navigate uncertainty, or direct intervention is necessary in times of crisis.

1.1. Mandatory stockpiles for critical goods

Government could explore the provisions within existing powers, or pass new legislation, to mandate private-sector producers or users of critical goods to maintain a level of excess production and/or storage capacity or demonstrate an ability to expand operations at short notice. In so doing, it could retain the authority to audit compliance in peacetime as well as tap on these capacities during crises.

Mandates for excess capacity in the private sector would help alleviate fiscal and logistical burdens in times of crisis. Market forces would help ensure that products with limited lifespans are expended before their expiry date. For private-sector providers, being compelled to build out production and storage capacities, particularly where they might have previously lacked an immediate incentive to do so, would result in greater long-term resilience to supply-chain disruptions as they become more able to ramp production up or down seamlessly and as necessary.

1.2. New requisition and production directives for emergencies

Where existing powers fall short, government could seek new authorities, separate to the Civil Contingencies Act (CCA), that granted it authority during less extreme crises to direct private companies to prioritise government orders; allocate materials, services, and facilities to response efforts; and restrict hoarding of goods. These directives would be more widely applicable while also being weaker than the CCA, given that some CCA powers may be excessive in circumstances that are less severe than those for which the CCA was originally conceived.

Noting that trade-off, it may work to develop a set of directives applicable to different types of crisis. The measures would be framed such that the government could more freely invoke them where the CCA may not be viable; they could also contain authorisation for companies to coordinate production and supply with each other without violating antitrust laws.

Such powers would reduce the government’s reliance on ad hoc market- based incentives to spur private companies to act in the interest of the public good during crises, thereby strengthening the production of critical goods in times of need. Provisions to protect private firms from antitrust scrutiny during crises would also reduce the risk borne by companies that support response and recovery efforts through greater coordination with competitors.

1.3. Cybersecurity mandates on system- wide vulnerabilities

Government could seek powers that give it a wider scope of authority in three areas. First, it might compel owners and operators of systemically important critical national infrastructure (CNI) to undertake specific government-prescribed cybersecurity directives, with the NCSC or the Centre for the Protection of National Infrastructure (CPNI) perhaps acting as a key conduit. Second, it might provide a mandate to intervene and assist directly during or after a significant cyber-attack on such businesses. Third, it might mandate that such businesses conduct regular due diligence on the cyber resilience of their supply chains.

While current intervention powers are reserved for extreme cases or emergency use, additional authorities would achieve several objectives. They would expand government’s sphere of influence in implementing cybersecurity mandates, enhance the depth of its reach, and be permanently in force. These changes would centralise nationwide cybersecurity governance, affording the government greater oversight over areas of critical national importance in anticipation of more challenging scenarios.

Moreover, mandatory cybersecurity measures would enhance societal resilience by strengthening the cyber resilience of CNI and their supply chains. The private sector would in turn benefit from reduced risk of potential disruptions caused by cyber-attacks, increased customer confidence, and reduced cyber-insurance premiums.

2. Government exercising its power as client

Taking advantage of its status as the nation’s largest procurer of goods and services, government could either build traction for, or outright require, enhanced corporate resilience efforts. This would influence private-sector behaviour without the need for legislative or regulatory instruments that might be regarded as overreaching.

2.1. Government contracting requirements

Government could require corporate commitments as part of major outsourcing contracts. These commitments might encompass both internal resilience objectives as well as external engagements. The former could include palpable capacity-building programmes to strengthen business continuity, contracts with cybersecurity experts for emergency support, asset hardening programmes, regular vulnerability assessments, formal risk management protocols. More precise features or investments could also be mandated, such as cyber-insurance coverage or systematic oversight of supply-chain vulnerabilities and risks. The latter, meanwhile, could involve providing demonstrable financial or human capital support to local community organisations for wellness and preparedness efforts, collaboration across community networks, and support for vulnerable populations.

Incentivising such actions through public procurement allows government to shape private-sector behaviour at minimal public cost. By making such commitments a prerequisite for bidding, the government could ensure that more companies — not just the successful respondent — actively and continually improve both their internal resilience efforts as well as their contribution to the community at large. Enhanced resilience efforts would not only improve private contractors’ business stability in the long run, but also enhance their reputation with other stakeholders.

2.2. Response and recovery procurement models

The government could create a suite of new emergency procurement models that relate to different crises or forms of desired private sector support. This would require the identification of likely key goods and services during response and recovery phases as well as potential vulnerabilities in supplier networks that could come under pressure during a crisis.

Specific models would likely require a mix of contingent contracts and crisis-specific procurement guidelines such as assessment criteria (supplier timeliness and resilience, business continuity arrangements, and other non- financial key performance indicators [KPIs]), and contract transparency. Such models would enhance public trust in contingency planning arrangements when normal levels of due diligence have to be suspended. Pre-signalling such opportunities would help likely private-sector providers hone their adaptive capacities to respond to suddenly changing needs and opportunities. Periodic testing in scenario-based tabletop exercises would help check their validity.

2.3. Technology innovation fund

The government could establish a technology innovation challenge fund that would galvanise the engagement and collaboration of stakeholders from different sectors. Areas of focus might be specific disruptions within the National Security Risk Assessment (NSRA), the cascading effects of sudden-onset events or slow-burn risks, or strategic or tactical response opportunities. Such a fund could form an element of a mission- based approach to national resilience wherein the government provides top-down guidance and funding but does not directly influence project ideation or design, thereby enabling an organic proliferation of bottom- up solutions.

This would not only advance technological approaches to resilience to a new level but might also yield solutions that could be shared with partner countries across the world. Additionally, the fund could help further the government’s ambition for the UK to become a ‘science superpower’ and generate approaches with dual-use applications. Private firms would gain access to funding that might otherwise be difficult to secure, in addition to a unique platform that facilitates collaboration, engagement, and sharing. Beyond their participation in the challenge, such resources might enable further internally led research and development efforts that in turn generate new business opportunities or even cycle back to boost national resilience.

3. Government stimulating markets

Where market forces principally dictate the speed and scope of innovation, economic or financial incentives may accelerate the crowding in of needed levels of capital and expertise. In some instances, government can adapt existing arrangements for national resilience ends; elsewhere, it might backstop possible losses that the market could not endure.

3.1. Research and development ecosystem

The government could cultivate an open and thriving research ecosystem where technology, innovation, and data can be combined in a pre-competitive environment to uncover win-win solutions for national resilience. Such an ecosystem would bolster the UK’s scientific and technological research efforts and could look to support both innovations solely for use within the national resilience ecosystem and also dual- use technologies.

Such efforts could culminate in cutting-edge solutions to resilience challenges such as the smart manufacturing of critical goods (PPE, medicines, etc.), analysing and modelling infrastructure challenges, early-warning systems that leverage evolving satellite technology, and surveillance and analytical capabilities that can detect emerging domestic and cross-border health threats. The innovation efforts of individual businesses would also benefit from an active and open network wherein data sharing and collaboration are both incentivised and facilitated.

3.2. Multi-peril insurance scheme for catastrophes

The government and insurance industry could develop a new scheme that embraces various complex perils, with a focus on extreme eventualities. The product might seek to incorporate a parametric approach (where appropriate), which would designate clear event triggers yet also incentivise — through lower premiums or faster access to funds — risk-mitigation efforts made by policyholders. This would deliver the twin benefits of speedy payouts (which would mitigate broader economic damage) and the gradual enhancement of organisational, and thus national, resilience over time.

Combining catastrophic risks that are uncorrelated and have different impact profiles could make for significant diversification benefits that would expand insurance capacity and coverage beyond what might be available via individual insurer offerings or separate pools. It might also be more efficient institutionally, especially regarding back-office activities.

Strategically, a broad scope would also address the frequent criticism of complex interventions — that they only address the last crisis and not the next. A single product that focuses on catastrophic events from various sources might be more appealing to customers concerned about extreme incidents than a suite of separate tail risk products with separate costs (see Exhibit 5).

An insurance solution might have several advantages over direct government financing, particularly where government support mechanisms need to be established hastily in a crisis. It could provide ex-ante transparency and certainty on the level of benefits that would be provided and leverage the existing claims payment infrastructure. It could attract private capital from insurance, reinsurance, and capital markets, which might absorb some of the losses even in cases where most of the risk is borne by government. Nonetheless, effective implementation would lower the burden on the public purse by reducing losses and facilitating faster economic recovery.

Exhibit 5: Public-private insurance/reinsurance models

From private to public:

Semi-private pooling reinsurance scheme

Joint entity created by insurers to pool risk and share knowledge

Participation may be voluntary or legally mandated

Financing primarily provided by the private sector, with limited (if any) initial government financing and typically no committed reserve

Public-private partnership (PPP) reinsurance schemes

Structured risk-sharing model between policyholders, insurers, and government

Government explicitly provides backing to the private sector to cap exposure and drive affordability

Participation may be voluntary or legally mandated

Public funds for noninsurable risks

Pure government setup, without any direct private involvement (other than aligning coverage)

Fund is created with a reserve, built up over time, that can be used to pay out claims in the event of a pandemic

Claims against the fund should be aimed at covering risk events that cannot be covered by existing insurance offerings

Pure government setup, without any direct private involvement (other than aligning coverage)

Fund is created with a reserve, built up over time, that can be used to pay out claims in the event of a pandemic

Claims against the fund should be aimed at covering risk events that cannot be covered by existing insurance offerings

Source: Marsh

3.3. Cyber-risk pool

To keep pricing affordable, enhance coverage, and generally improve cyber resilience, government and the insurance industry could develop a levy and pool system to support cyber-insurance accessibility for UK businesses. Such a scheme would require appropriate backstops, modelled on other government-backed reinsurance schemes.

Two potential areas of focus stand out. First, providing coverage for ‘infrastructure loss’ events or catastrophic damage to key digital infrastructure networks that result in widespread impacts. Second, supporting access to coverage for SMEs by assisting with affordability and enhancing the specialist support that already plays a role for insured businesses before, during, and after an incident.

A ‘Cyber Re’ could help raise baseline cybersecurity practices of UK organisations as well as alleviate payouts in crises if it included provisions that required good organisational cyber-risk management. Government could also encourage insurers to adopt minimum security standards in risk assessments through, for example, Cyber Essentials accreditations. The government might also wish to mandate a certain level of cyber coverage for responses to public-sector tenders, similar to existing requirements on public and private liability coverage. Government could also consider passing supporting legislation that contained provisions on mandatory data and threat information sharing.

3.4. Scaled-up resilience/adaptation bonds

Government could expand the scale and scope of the resilience and adaptation bonds it already issues and actively encourage private- sector beneficiaries to participate (a resilience bond is a fixed income instrument issued to raise low-cost private capital for projects that enhance national resilience and generate investment returns). This would facilitate government-initiated cost-sharing with the private sector on ‘hard’ measures such as sea defences, levees, and infrastructure toughening as well as ‘soft’ measures such as catchment restoration and forestry management initiatives. Government could also support the design process of bond-backed developments by providing project financing expertise from HM Treasury and grants for modelling as well as creating facilitation guidelines and best practice documentation.

At a time of increasing institutional investor interest in opportunities with strong ESG profiles, offerings in this area would present new investment opportunities with a distinct risk-return profile. Distributed ledger technology could support the traceability of projects and their impacts, and also reduce transaction costs. In the long run, expanding this form of bond issuance would accelerate progress in sustainable development within the UK.

4. Government facilitating innovation

Often the right conditions are critical for liberating private-sector capabilities, especially where collaboration is required. Against this backdrop, government can act as a convening power, help reduce barriers to engagement, enable unexpected solutions to emerge, and provide a frame that ensures value both for private-sector participants and national resilience.

4.1. Streamlined data-sharing arrangements

The government could clarify or adapt legal guidance on data sharing, including any safe harbour arrangements in a crisis, to alleviate uncertainty and encourage participation. This could be complemented by standard templates for data access agreements, collaboratively developed with business, that would help reduce cost and confusion further, especially for smaller firms. These foundations could be enhanced by more forward- thinking data-sharing strategies, universal metadata standards, the development of portals or data lakes, and the design of appropriate security provisions for sensitive data.

By enabling greater access to diverse datasets before and during a crisis, the government could leverage the speed and innovation of the private sector in response and recovery as well as attain more accurate situational awareness in fast-moving or complex crises. Improved guidance and clearer standards would reduce costs and operational inefficiencies for private firms seeking to build out their data-driven capabilities.

4.2. Open data sandbox and complex analysis platform

Possibly as part of National Digital Research Infrastructure plans, the government could provide researchers, civil society, and the private sector with access to diverse, high-fidelity, interconnected, longitudinal data and state-of-the-art analytical tools through a data sandbox platform. This would facilitate the integration and interrogation of different public and private data sources, including (with appropriate privacy safeguards) de-identified data — such as income, demographics, and health statistics — that come from different government departments. Especially where the opportunity arises to support projects for the public good, the government could also grant public access to large computational resources within the sandbox that are designed for artificial intelligence or machine-learning applications to enable advanced analytics that would otherwise be too expensive for SMEs and researchers.

A powerful platform with appropriate safeguards could funnel more diverse, high-quality data into a centralised repository, thereby equipping government bodies as well as other stakeholders across society to better tackle national resilience challenges and conduct more comprehensive vulnerability assessments and research into effective crisis response strategies. It could, moreover, facilitate the combination or comparison of distinct datasets to derive cross-cutting, interdisciplinary insights that may serve as a bedrock of innovation — as with recent efforts linking mobility and health data to assess the effectiveness of COVID-19 lockdown measures. Access to the sandbox’s databases and resources would also help fast-track data-driven insights on vulnerabilities and resilience strategies from private firms to supporting resilience efforts such as modelling the pandemic. This sort of work could also serve other national priorities (e.g. economic security, climate mitigation) and enhance the standing of UK science.

For further details on context, analogues, and considerations, click here

4.3. Real-time data integration into the National Situation Centre

The government could ensure that the recently announced National Situation Centre (NSC) is equipped to integrate data from a range of sources. These might include ever-growing real-time data from smart meters and the Internet of Things on mobility patterns, public sentiment streams, environmental factors (such as water height, wind speed, temperature), stockpile levels and the movement of key goods, and response capabilities.

Leveraging private-sector data would provide the NSC with a more holistic and dynamic dashboard representation of the risk landscape, response capabilities, and societal capacities that might better anticipate cascading impacts in times of crisis. By collecting, cleaning, and integrating such datasets over time, trend analysis could also support the development of early-warning signals for emerging threats and help resource allocation in preparation for and during events.

Such a capability would also be foundational for exploring different planning scenarios that would better ensure the continuity of societal functions. Moreover, improvements to data availability, matching, and standardisation would support national risk assessment work by compiling a national data taxonomy to help identify data gaps that might be filled by further research. Such efforts would also allow for the provision of intelligence to the private sector, especially critical infrastructure sectors such as health, transport, and food, generating enhanced insights into emerging supply- chain risks and demand surges.

4.4. Critical national infrastructure interdependency stress testing

Government could facilitate sector-wide and cross-sector stress testing of CNI assets and their supply chains against major contingencies. Regulators would need to coordinate efforts and design scenarios that tested the collective strength of the UK’s critical networks against extreme and compound threats. Periodic stress testing would allow CNI owners and operators to understand what and how much is at risk, including from external dependencies, as well as examine how to enhance preparedness and resilience through targeted measures for critical network elements. A government-led forum could facilitate dialogue to share learnings in a non-competitive setting.

Such complex stress testing would involve the development of CNI simulation modelling capabilities by integrating public and private data on networks, dependencies, supply chains, and failure thresholds in a centralised national repository to be used by operators for vulnerability assessments. These capabilities would enable threat scenarios to be analysed, losses and damages to be estimated, and mitigation actions to be designed and tested. A centralised approach to modelling and stress testing would enable enhancements over time to benefit operators.

For further details on context, analogues, and considerations, click here

4.5. Public-private sector exercises across the crisis cycle

Public agencies could more actively invite relevant private-sector businesses, particularly those operating critical infrastructures and systems, to participate in joint crisis exercises for preparedness, response, and recovery. In certain instances, there may be a case for mandating involvement. These exercises might focus on validating emergency plans, developing staff capabilities, testing procurement procedures, and other critical activities. To enable this, private-sector involvement would need to be explicitly included in relevant doctrines such as the Resilience Capabilities Programme and associated guidance on emergency planning and preparedness.

The inclusion of actors from different sectors (discussion-based or tabletop exercises being less burdensome) would provide more opportunities for public-private interaction and mutual learning. Not only would this likely reveal unanticipated vulnerabilities and operational snags, it would also strengthen relationships and trust, enhance an understanding of different capabilities and working styles, and develop muscle memory that can be accessed in the future. Companies participating in these exercises would gain a better understanding of their own exposure to crises and business continuity weaknesses.

5. Government cheerleading business initiatives

Where there is alignment on the core goals, many initiatives are likely to arise from the private sector. Under such circumstances, government may wish just to provide input or guidance, encourage expansion, or otherwise promote more widely.

5.1. Metrics for asset resilience and disclosure

To incentivise timely asset upgrading and maintenance, government could advocate for the inclusion of metrics on asset resilience and risk governance — including design standards, maintenance records, and risk-engineering reports — in outputs from rating agencies and investment data providers. Additionally, government could also lead by example and publish such metrics on its own assets to encourage more widespread adoption and ultimately induce a paradigm shift towards a convention of asset resilience reporting and disclosure.

More granular metrics and improved reporting would help long-term investors direct capital towards assets that are better managed for resilience, thereby raising questions for owners and operators of less resilient assets. As rating agencies adopted such metrics, the underlying data could also inform the cost and design of loans, which would yield cost savings for private firms and hence create financial incentives for better asset management in the long run. Such metrics could also be used as the key trackable KPIs required for ongoing access to sustainable and transition-linked finance. The net outcome would be greater trust in the reliability of critical societal functions.

5.2. Private-sector code(s) of crisis conduct

Government could encourage industries to develop crisis codes of conduct that would help establish and clarify expectations as to reasonable behaviour by private firms during contingencies that trigger a State of Emergency declaration or during other extraordinary circumstances. Any such code should include ‘best-practice’ provisions — developed by those industries with government input — on critical issues including data sharing, pricing, intellectual property rights, treatment of employees and suppliers, and capacity management. For example, a code of conduct for biopharmaceutical companies might include guidelines on licensing and supply agreements for essential drugs during a pandemic

Successful implementation of any private-sector crisis code of conduct, particularly for firms providing critical services, would bolster societal resilience as private firms would be better placed to more seamlessly and efficiently allocate resources and capabilities during crises. This would accelerate private-sector responses under emergency circumstances, resulting, for example, in shorter procurement timelines. A formal code that helped clarify expected behaviours and was widely adopted would empower individual firms to cooperate without fear of being disadvantaged relative to their peers.

5.3. Employee engagement for resilience

Government could encourage companies, especially large employers, to enhance the disposition and capabilities of their workforces. A multi- pronged strategy might blend the inclusion of a resilience dimension into health and benefits offerings, educational opportunities on risk mindfulness, employer-based training for actions to be undertaken in the event of specific contingencies, and support for local resilience-related community and charitable organisations — such as through offering employees paid leave to undertake community-based volunteering activities.

Expanding these efforts would benefit employees as individuals in major life choice decisions, contribute to a stronger corporate risk culture, and deepen employee loyalty. More broadly, it would help foster a ‘whole- of-society’ culture-oriented approach to national resilience that would reduce the need for government intervention.

Conclusion

Sustained supply-chain challenges, extreme weather events, large-scale cyber-attacks, energy crises of different kinds, and an evolving COVID-19 virus all argue strongly for national-level preparedness and resilience to be strengthened and made more supple. Indeed, despite widespread hunger up and down the country to return to normality after the constraints of the past couple of years, it is evident not only that the pandemic is still with us but that new crises have already surfaced and further challenges and contingencies lie just over the horizon.

Against that backdrop, a new national resilience strategy — which asks hard questions of the country’s performance, targets the future, contains bold ideas, and embraces the participation of all sectors — is much needed. Deep-seated tensions need to be acknowledged and worked through, some of which set the demands imposed by a more challenging risk environment against our values as a liberal and market democracy. Nonetheless, the opportunities for stronger public-private engagement, based on true partnering for shared goals, are numerous and huge. But, as should be apparent from this report, framing interactions and collaborations in the right way will be crucial for achieving a lasting enhancement of capabilities and effort.

Appendix

1. Government directing private-sector priorities

1.1. Mandatory stockpiles for critical goods

Context: The burden of stockpiling critical goods against future crises currently falls most heavily on public- sector entities, which may not hold usable supplies for all emergencies. The private sector’s ‘just-in-time’ manufacturing and supply processes, resulting from a pursuit of efficiency, mean that companies often struggle to meet surge demand following the onset of a crisis. Together, these arrangements can lead to rapid exhaustion of inventories and damaging delays in restocking.

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, national stockpile shortcomings and procurement strategy weaknesses contributed to shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), human-resource constraints, and large amounts of stock that no longer met current safety standards. The pandemic stockpile at the time was geared towards an influenza outbreak and not a novel virus like COVID-19; moreover, government faced questions about being slow to engage industry in ramping up domestic production of PPE.³³

Idea and value: Government could explore the provisions within existing powers, or pass new legislation, to mandate

private-sector producers or users of critical goods to maintain a level of excess production and/or storage capacity or demonstrate an ability to expand operations at short notice. In so doing, it could retain the authority to audit compliance in peacetime as well as tap on these capacities during crises.

Mandates for excess capacity in the private sector would help alleviate fiscal and logistical burdens in times of crisis. Market forces would help ensure that products with limited lifespans are expended before their expiry date. For private-sector providers, being compelled to build out production and storage capacities, particularly where they might have previously lacked an immediate incentive to do so, would result in greater long-term resilience to supply-chain disruptions as they become more able to ramp production up or down seamlessly and as necessary.

Existing analogue(s): The UK requires major businesses producing, supplying, or using petroleum products to ensure minimum stock levels at all times³⁴ In the electricity sector, the Capacity Market ensures security of electricity supply by providing a payment for reliable sources of capacity³⁵ Other countries have successfully responded to COVID-19 on the back of stockpile mandates. Finland’s National Emergency Supply Agency (NESA) drew on its policy of mandating certain suppliers to maintain stockpiles of indispensable goods such as grain and medical supplies, while simultaneously storing some of those suppliers’ stock in its own warehouses. In ‘peacetime’, suppliers can sell the goods stored in NESA warehouses and exchange older models for new stock.³⁶

Key considerations: The NSRA and subsequent planning assumptions, based on inputs from different sectors, would be foundational in specifying what supplies might be needed, the standards required, how much of each item should be stockpiled, and the length of notice at which they would need to be delivered. Not all goods may need to be stockpiled if firms can prove that they can ramp up production (especially of items with a short shelf life) at short notice. Even for these, it would be vital to understand the short notice availability of raw materials alongside other potential bottlenecks, including skillsets and storage and transportation capacities. It would also be important to monitor and audit the possibly large number of new, decentralised stockpiles and production facilities, and also the impending expiry dates of goods — where relevant.

Moreover, given the net benefit to the public purse, it would be important to explore whether or where government should incentivise companies to hold more critical goods inventory than they otherwise would, as doing so would have working capital and cash flow impacts as well as storage costs.

1.2. New requisition and production directives for emergencies

Context: Although private sector companies have access to a wide range of assets and capabilities that would significantly strengthen national crisis response and recovery efforts, they may not feel incentivised to meet surge demand during crises and, depending on the circumstances, may deem it more advantageous to hoard supplies. The Civil Contingencies Act (CCA) contains provisions that theoretically enable government to address these issues, although short review windows and a ‘triple-lock guarantee’ limit its invocation to a subset of phenomena in accordance with a narrow definition of ‘emergency’.³⁷

Consequently, the CCA was not activated during the COVID-19 crisis — arguably the greatest challenge the nation has faced since World War II. In the years since coming into force, commentators have noted the government’s disclination to invoke the CCA due to its perceived limitations.³⁸ There is hence a need for new, distinct directives that supplement the CCA by permitting emergency powers in response to a wider range of threats, albeit without encouraging government overreach.

Idea and value: Where existing powers fall short, government could seek new authorities, separate to the Civil Contingencies Act (CCA), that granted it authority during less extreme crises to direct private companies to prioritise government orders; allocate materials, services, and facilities to response efforts; and restrict hoarding of goods. These directives would be more widely applicable while also being weaker than the CCA, given that some CCA powers may be excessive in circumstances that are less severe than those for which the CCA was originally conceived.

Noting that trade-off, it may work to develop a set of directives applicable to different types of crisis. The measures would be framed such that the government could more freely invoke them where the CCA may not be viable; they could also contain authorisation for companies to coordinate production and supply with each other without violating antitrust laws.

Such powers would reduce the government’s reliance on ad hoc market-based incentives to spur private companies to act in the interest of the public good during crises, thereby strengthening the production of critical goods in times of need. Provisions to protect private firms from antitrust scrutiny during crises would also reduce the risk borne by companies that support response and recovery efforts through greater coordination with competitors.

Existing analogue(s): Provisions already exist in the CCA for requisitioning assets and directing private-sector production — new directives would simply lower the thresholds for activation. The US Defense Production Act, which can be enacted through an Executive Order, contains activation mechanisms and conditions that are far more lenient than those of the CCA.³⁹ Crucially, the Defense Production Act empowers the federal government to direct private-sector suppliers even during peacetime to support causes including emergency preparedness activities, the protection or restoration of infrastructure, and efforts to mitigate terrorist threats.