International Models of Emergency Management Involving Civil Society

Introduction

The preparedness of our communities to help in crises response is a key factor in the resilience of our society. Good practices are apparent when formal structures and resources combine with civil society volunteers to enhance resilience at local level. This report provides four international examples of how civil society has been engaged in societal resilience. We present case studies from Chile, USA, Canada, and New Zealand to provide examples of the different models of official and unofficial engagement with response mechanisms.

To summarise the approaches:

- Chile developed a national youth volunteer programme as a feature of their model ‘Building Resilient Communities in Chile: Spontaneous Volunteering Programme’. There is both national and local recognition of the importance of youth involvement as spontaneous volunteers in a crisis situation, evident during Covid-19. Tracking the experience and contribution of youth volunteering informs the plans for the 2030 National Youth Volunteering agenda.

- USA operationalises a federal model called Community Emergency Response Training (CERT). Emergency volunteers, across all states, receive the same training that has been designed and authorised by This model is compulsory for all CERT disaster volunteers who want to support emergency providers.

- Canada has developed a national model called Search and Rescue Voluntary Association of Canada (SARVAC). Funded 95% by the Federal Government Contribution Agreement, it is integrated with the National Search and Rescue As a federal model, it provides compulsory extensive training and works alongside other voluntary organisations.

- New Zealand has developed a community volunteer model called Community Emergency Hubs, which provides support to communities in The Hub Guide provides instructions for the management, responsibilities and safety of the volunteers. Examples from Wellington show how hubs have supported emergencies, such as floods and Covid-19.

Across these case studies, this report highlights:

Integration with state and official responses. Each of the four models has a different approach towards integrating official/state and volunteer responses, the choice of which is influenced by the national context and the nature of the state infrastructure.

- Chile’s approach to harnessing the valuable youth resource involved integration in a practical and responsive way – drawing on state and business to provide what was needed to protect, enable and validate their contribution.

- The US approach to CERT deliberately seeks to draw community response activity into the mainstream – funding, standardising, delivering and accrediting the scheme for seamless integration with official operations.

- Canada’s SARVAC’s approach is less centralised, focussing on co-ordination and accreditation within the context of regional and provincial autonomy.

- The New Zealand hub model is centred on a standardised set of resources and roles, providing a consistent platform on which to build autonomy and flexibility at local level.

Integration with state and official responses. Each of the four models has a different approach towards integrating official/state and volunteer responses, the choice of which is influenced by the national context and the nature of the state infrastructure.

- Chile’s approach to harnessing the valuable youth resource involved integration in a practical and responsive way – drawing on state and business to provide what was needed to protect, enable and validate their

- The US approach to CERT deliberately seeks to draw community response activity into the mainstream – funding, standardising, delivering and accrediting the scheme for seamless integration with official

- Canada’s SARVAC’s approach is less centralised, focussing on co-ordination and accreditation within the context of regional and provincial

- The New Zealand hub model is centred on a standardised set of resources and roles, providing a consistent platform on which to build autonomy and flexibility at local level.

Differences in the official training provided to civil society to support emergencies. Training approaches lead to different levels of autonomy being given to community groups – including to spontaneous volunteers who emerge from society, follow training procedures, and then work with the local government response. While some of the case studies train civil society volunteers extensively (USA and Canada), others focus on intuitive activities where less training is needed (New Zealand) or encourage and enable spontaneity where training is not possible (Chile). As with integration, the choice appears to reflect national context, with training approaches heavily informed by experience.

NGOs as a long-standing facilitator to civil society involvement. Civil society organisations and NGOs have important roles to play in representing, co- ordinating, and encouraging the identification of support and needs at local level. The Red Cross has a strong presence in the four countries discussed and provides a wide range of function associated with volunteering. As such, NGOs can be seen as a bridge between formal state or government agencies and the wider community, with an ability to understand and operate in both formal and informal structures – often simultaneously.

The report authors would like to acknowledge Fernando Padilla Parot and Jenny Moreno (Chile), Suu-Va Tai (USA), Cindy Sheppard and Paul Olshefsky (Canada), and Paul Cull (New Zealand) for their knowledge that has been used to inform this report.

The remainder of this report comprises a full description of each case study in turn.

Case Study 1: Chile, Spontaneous Volunteers

Building Resilience Communities in Chile: Spontaneous Volunteering Programme

Chile, with a population of approximately 19.5 million (2022), is a country that is well used to crises. The country is vulnerable to crises arising from the instability of its geographical location – being at the intersection of three tectonic plates – as well as from being vulnerable to natural disasters. Crises include earthquakes (Valdivia, 1960, Coast of Central Chile, 2010), seven tornadoes within 24 hours (Central and Southern Chile, 2019), floods (Atacama, 2015) and wildfires (Torres del Paine, 2012; Valparaiso, 2014, 2019; South Central Chile, 2017). This naturally volatile country is supported by a community of volunteers who provide a wide range of support, including working on community projects, caring for animals, and providing support in hospitals. Volunteers have also been recruited from other countries to protect Chile’s forests and work on humanitarian projects, including providing support for homeless, disabled, and older people.

Following the end of the Pinochet era in 1991, public institutions and the media were cautious to encourage youth participation and activism (Munoz-Navarro, 2009). The return to democracy was slow and, in 2003, the Centre for the Research and Promotion of Human Rights incorporated a group of young people for voluntary action which led to official youth volunteering as a state-supported activity (Torney-Purta et al, 2016).

This case study highlights a significant achievement for Chilean youth. Official training by the state has enabled young people to be involved in volunteering with local and national government. The programme was conceptualised in the south of Chile, where it was noticed that 90% of spontaneous volunteers (SVs) who turned up to help when crises happened were young people. Volunteering is not new to Chilean youth and, in 1995, the Stipend National Service Volunteering (SNVS), which provided a one-year subsistence payment, was established to provide support to those in most poverty (Bryer et al, 2016).

Between 2017 and 2018 a national government-led (official) youth volunteering framework was developed for Chile and also adopted by Argentina. This built on ISO 22319 ‘Guidelines for planning the involvement of spontaneous volunteers’. For Chile, this involved developing a national approach for spontaneous volunteering – initially drawing on the experience of local and national representatives from 45 stakeholders, including emergency response teams, army officers, universities, civil society organisations, municipal officers, governors and national government officers.

SVs Responding to the Valparaiso Fire

The guidelines were tested at the Valparaiso Christmas Fire in 2019. Response to the fire involved 300 volunteers, mainly young people, some of whom were initially injured at the start of the fire and were struggling because of underlying health issues like high blood pressure or asthma. Recognising the potential vulnerabilities of spontaneous volunteers (SVs) the local government, together with established voluntary organisations, private organisations and local leaders, developed a partnership to co-ordinate the management of the SV volunteers by supplying PPE, tetanus injections vaccinations, sun cream and insurance. Within three days the numbers of injured volunteers reduced by 98% and the guidelines helped to make SVs safer and more effective.

Key findings from this fire showed:

- Cost was important to government and the types of facilitating support that SVs required were not expensive – subsequently, SVs were provided with low-cost safety resources.

- Co-ordination of the different partners was most important to ensure safety and effectiveness.

- Local leadership and knowledge of the area was essential to enhance the effectiveness of SVs.

- Local businesses’ help during this crisis was highly valued as enhancing performance.

SVs Responding to Talcahuano Tornadoes

SVs were also co-ordinated in response to tornadoes that landed in Talcahuano in 2019. Some 90% of the volunteers were youth volunteers, who were at high school or university and wanted to provide aid. Maps of the path of the tornado using a GPS mapping application were downloaded by SVs and used to assess the destruction created by the tornado. This information provided local intelligence at speed to the municipality and helped them to deploy resources and conduct task co-ordination.

Analysis of the SVs’ response to the tornado showed:

- The growth of partnership working, particularly the inclusion of youth SVs, was successful in supporting response and recovery.

- SVs mobilised quickly – the time for the SVs to begin to respond and to reach the registration point at City Hall was within 20 minutes.

- Students from local universities spontaneously volunteered from different cities.

- The municipality supplied all SVs with the appropriate PPE and quick training to ensure safety.

- The municipality was concerned that the lack of local knowledge of students who had travelled from other cities, could put them in danger.

Measures taken to enhance the deployment of SVs included:

- 200 SVs were briefed about the disaster, which included mental health briefing and counselling to understand the psychological impact of the tornado.

- Transport was provided to volunteer organisations to work in tandem with the SVs.

- SVs tasks included helping with clean-up stage activities such as repairing rooves and windows and packing boxes.

- Effective use of local leaders and supervisors managing communication and co-ordination.

Volunteers arriving from other districts highlighted the importance of co-ordination across the regions and partnership working.

Youth Volunteer National Policy

The lessons from these two incidents informed the National Policy for spontaneous volunteering. The extent of disasters in Chile meant the Government did not have the resources to deal with them all. Subsequently, national government welcomed the youth input and aimed to establish effective partnerships with young people to develop the skills and competencies for future challenges. There is wide national and local recognition of the importance and contribution of youth involvement as SVs in crisis situations.

These goals are explicit in the 2030 National Youth Volunteering agenda which recognised that it was important to:

- Establish a youth volunteer programme to further develop youth volunteer participation as a protagonist of change.

- Develop an operational process involving a revolving system of networking and action.

- Support the learning experience for youth, including developing their skills for current and future competencies.

- Build communities to promote youth volunteering opportunities from the local to the national levels.

Ecosystem and Management

Initially there was no management system to support youth SVs.

The development of the ecosystem involved:

- Engaging permanent volunteer youth teams in all regions.

- Developing a network across all of the regions that included different sectors (public, private, third sector and academia).

- Joining up working to include online speed communication and co-ordination.

- Volunteer management development located in the National Institute for Youth (INJUV).

- Regional offices of local government report to INJUV national government.

- The youth volunteer management process involved four key areas:

- Risk assessment of the disaster zone to evaluate the feasibility of working with volunteers.

- Establishing a reception system as a volunteer centre (VRC) across all sixteen regions in Chile.

- Co-ordination with local networks, including local government, civil societies, and local volunteers.

- Delivery of permanent training to spontaneous youth volunteers.

As a national agency, INJUV encourages networking to communicate societal resilience in local communities at the local and national levels. Networking across all of the partners, volunteers, civil society, public and private is essential to support the system. Youth activities were anchored in the learning experience and their training from emergency planning. More recently, having permanent volunteers established in each region enables movement between regions when a shortage of volunteers arises.

Youth Volunteer Response to Covid-19

These established networks of youth volunteers were invaluable during Covid-19 when young people could not travel from one city to another, especially before an online volunteering system was created. Covid-19 safety measures were enhanced to include online specialised training for organisations and volunteers. Additional provision included face masks and portable sinks to allow handwashing. Online regional youth volunteer initiatives encouraged more young people to join and receive training to increase the response capacity.

The development and assessment of this initiative has focussed on volunteer safety, impact and sustainability as priorities. During this period there was a focus on providing activities for people who were confined to their homes for various reasons, to support their health and well-being. In one region alone, 315 youth volunteers delivered food and essentials. Similar plans were also utilised for managing youth SVs in Argentina.

Case Study 2: USA, Community Emergency Response Teams (CERT)

National CERT Association

The US has a strong tradition of volunteering which adds a substantial amount to their economy and is credited with enhancing personal well-being. For example, during 2018 approximately 22 million baby boomers (people over the age of 50) volunteered in the USA, adding $54.3 billion of value to their communities (Nakamura, 2022). Numbers of volunteers have decreased across the USA in recent years (Grimm, 2018). In contrast to this, the Serve America Act (2009) advocates a dramatic increase in US volunteering by 2050 and prescribes a recruitment expansion incorporating a diversity of volunteers across the country (Nesbit & Brudney,2013). The Serve America Act has three principles: (1) to expand opportunities for Americans to provide volunteer service; (2) to strengthen the non-profit sector and support innovation in the sector; and (3) to increase the accountability and cost effectiveness of volunteer programs. The growth of Community Emergency Response Teams (CERT) to provide a local resilience capability as a US national volunteering program illustrates a prime example of this expansion.

Background

Established as a volunteer program by the Los Angeles City Fire Department in 1985, the basic curriculum of CERT was changed in 1994 to make it suitable at the national level. FEMA heightened the profile and expansion of CERT by moving the program into the Citizen Corps program in 2002. CERT was trailed across the US under the banner, “Are You Ready? A Guide to Citizen Awareness”. CERT was consolidated as a national volunteer program and FEMA provided grant funding until 2011. Subsequently, the CERT program has been operationalised in all 50 US states and adopted internationally. Funding from FEMA and individual states depends on the scale of an individual crisis.

CERT is a feature of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) premiere program to support community action and resilience. FEMA owns the CERT training curriculum and has final decision on any proposed updates in the system management. FEMA provides and controls all instructor training and program management for CERTs in US, as well as information to help prepare, respond and recover from disasters. Individual states have control for vetting any local programs and enforcing FEMA guidance. Local sponsoring agencies are responsible for their own programs and their own volunteers.

Currently there are approximately 3,000 CERT programs, of which 500 are in California. For any new CERT program, the core team is established, comprising a program manager instructor with the required skills and equipment and access to a classroom for the training.

The team educates volunteers about disaster preparedness for the hazards on their area. Hazards include: avalanche, earthquake, extreme heat, fires, floods, hurricanes, landslides, nuclear emergencies, thunderstorms, tornadoes, tsunami, volcanoes and winter storms. Volunteers are trained in basic disaster response skills, such as fire safety, light search and rescue, team organisation, and disaster medical operations. By providing a nationwide approach to volunteer training professional responders can trust CERT volunteers during disaster situations, knowing their methods and abilities, allowing professional teams to focus on more complex and hazardous tasks.

The US promotes CERT through presentations delivered by CERT volunteers. This can entail managing outreach booths at preparedness fairs or explaining training procedures for community members and organisations. CERT volunteers also undertake a variety of tasks that help the public. For example, this could be traffic control or radio communications or sandbagging. Volunteers are also involved in search and rescue operations, as well as providing emergency operations support.

CERT Training

CERT training provides a choice between hybrid training and all classroom-based training. The hybrid training is comprised of 12 hours independent study online, which is followed by 16 hours in the classroom to learn skills, training, and take a disaster simulation exercise. Refresher training is also available.

There are different types of CERT training. The eight basic training modules are two to three hours long and include:

- Disaster preparedness: provides an introduction to the course and modules, explaining what disaster preparedness entails, including the role of firefighters, and providing examples of major disasters.

- CERT organisation: covers how volunteers understand and organise their responsibilities as well as those of other team members, so they understand the CERT procedures.

- Support for disaster medical operations: explains basic skills on how to triage patients who need medical aid, for example, medical professionals train CERT volunteers in how to stop bleeding and how to work with people in shock.

- Disaster psychology: explains what to say and what not to say in a crisis situation.

- Fire suppression: provides instruction on fires, when to leave a fire, and provides hands-on practice with fire extinguishers.

- Utility controls: teaches people how to identify where gas and electric controls are located and how to turn them off. They are supported by utility control employees who are the only people allowed to turn the gas back on.

- Light search and rescue: involves listening and supporting people, learning how to lift without harming yourself, and knowing when it is time to remove yourself from the crisis for your own safety.

- CERT and terrorism: involves how to identify suspect items and where to report these.

CERT programs offering additional training include: first aid; using amateur radio; sheltering; search and rescue; incident command system; damage assessment; volunteer management; national incident management system; community coalition building; CERT animal response; and decontamination.

CERT advanced programs include:

- Train and Release: provides 20 hours of training and includes First

- Train and Retain: involves emergency management via the Incident Command System and how to work with First Responders and Emergency Management during a

Profile of CERT Volunteers

In 2020 CERT conducted a ‘Certification’ Survey, with a return of 380 surveys. The aim was to gain an understanding of the communities they serve as well as the types of CERT sponsoring organisations, and where CERT volunteers were mainly located. This showed that 38% of volunteers were drawn from the public at large; 12% came from neighborhood groups; the ‘others’ category covered 9%; teens and youth were 8%; faith based organizations 8%; businesses 7%; government groups 7%; colleges and universities 5%; people with disabilities 4%; and military groups 2%.

In 2022 there was a hazard awareness initiative jointly organised by FEMA and the Spirit of Adventure Council, which saw 12,700 youth scouts undertaking community service tasks. By providing scouts with the skills for preparedness the intention is to integrate youth into emergency planning as the teen arm of CERT (Vocatura, 2022).

CERT Funding

During Covid-19 CERT resources went to: food pantry support; food supplies delivery; virus testing site support; vaccination clinic transport; sheltering and mass care, call center support; Covid-19 safety education; personal protective equipment distribution and mask manufacturing. CERT volunteers were involved in a contact tracing program, which involved working remotely but also identifying new solutions for contact tracing (Shelby et al 2021).

Political will can differentiate between different states in terms of FEMA’s control of funding for CERT Teams. For example, Willison et al (2018) questioned the disparities between the funding allocated for the response to hurricane disasters in Texas and Florida compared with that in Puerto Rico. Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria were similar destructive forces during 2017, with similar strength and impact, however more funding was available for Hurricanes Harvey (Houston) and Irma (Florida) compared to Hurricane Maria (Puerto Rico). This resulted in 2,975 more casualties in Puerto Rico compared to the other states. By quantifying FEMA’s differences in funding response and recovery, the inequities between resourcing were exposed (Willison et al, 2018).

CERT Cyber Security Model

Not all CERT response relates to on-the-ground activities. Some aspects are more specialised, for example a cyber-security model has been developed in the Carnegie Mellon University Software Engineering Institute to develop critical software engineering. Highly qualified CERT engineers work to protect and sustain assets that are essential to the US cyber dependent mission ensuring that they continue operating during and through the recovery of disruptive events. Cybersecurity risk management develops tools and processes that enable continual operational continuity in times of US attacks (Stewart, 2018).

Case Study 3: Canada, Search and Rescue Voluntary Association of Canada

Search and Rescue Voluntary Association of Canada (SARVAC)

The mission of the Search and Rescue Voluntary Association of Canada (SARVAC) is to save lives by fostering, co-ordinating and encouraging excellence in volunteer research and rescue organisations in Canada. SARVAC is integrated with the National Search and Rescue Secretariat (NSS). Search and rescue in Canada is not delivered or executed by a single organisation, rather it is a combination and co-operation of multiple federal, provincial, municipal and volunteer organisations. As part of that effort, SARVAC’s vision is to have a national community of skilled search and rescue volunteers whose contributions are valued and supported by the public and all levels of government.

Approximately 38.25 million people live in Canada and SARVAC serves 13 Provincial and Territorial (P&T) ground and rescue associations. Established in 1996, it is registered as a not-for-profit volunteer Canadian educational organisation underpinned by the principle of saving lives. To achieve this principle, SARVAC supports, co-ordinates, develops, informs, promotes and implements search, rescue and emergency response. SARVAC currently has approximately 265 teams comprising 9,143 SARVAC volunteers who provide search and rescue services on land and inland water. These volunteers operate as ground search and rescue volunteers (GSAR).

Governance and Activation

SARVAC’s Board of Directors is comprised of representatives from all 13 P&T areas, however it is the police authority that has jurisdiction over the GSAR volunteers in all 13 P&T areas, as well as responsibility for their activation and deployment.

SARVAC is connected to the National Search and Rescue Secretariat (NSS), which is a centre for SAR co-ordination and promotion in Canada. The role of NSS is to co-ordinate central activities for the federal element of search and rescue. It also works with the P&T search and rescue authorities and police services to standardise the quantity and quality of SAR services available to the P&Ts and publishes a bilingual SARscene magazine. The RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police) also have a role in SAR, and their mounted police are most likely to call on Foothills SAR to search for missing persons. Other organisations involved in SAR include: Canadian Forces SAR; Civil Air Research and Rescue Teams; Canadian Coast Guard and Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary.

Volunteer Management

In 2016 the Canadian Red Cross conducted an assessment of the Canadian Voluntary Sector capabilities and capacity in emergency management, to gain more understanding of how to enable volunteer emergency management (Mackwani, 2016). Their findings showed that out of the 25 emergency management capabilities required only two were missing – those two being structural and non-structural measures for mitigation; resilience and restoration of critical infrastructure. In terms of capacity and capability it was recognised that there was a vibrancy in volunteering and that was evident in volunteers’ capacity both whilst training and in their surge capacity. Further evaluation areas were recommended: whether more volunteer certification was needed; and whether the investment in training led to a return in the form of increased retention. One challenge faced by the National SAR program lies in bringing all the independent systems together without having control over them (Leroux, 2018).

Volunteer Training

GSAR teams conduct most of their training in-house, but external SAR training providers may also be used. GSAR training is based on national training standards developed by SARVAC. The standards cover basic core competencies required for curriculum development, and regional differences in training requirements are based on environments and operational needs.

Technical training includes helicopter, high angle, swift water, K9, water rescue, and drone operation, and these elements are provided by certified external trainers.

Volunteer Recruitment and Retention

Recruitment of volunteers is conducted by the GSAR teams within their regions of operation and is done mainly through word of mouth, social media, and recruitment events.

Retention of GSAR volunteers is challenging because it is variable across locations of GSAR teams and the effect of call volumes driving quiet and busy periods. Volunteers’ expectations are changing as they increasingly look for a solid program structure, more professionalism, higher profile, and the ability to be mobile whist retaining trained status. To address retention, SARVAC is rolling out a recognition initiative – a national certification pilot project for Searchers, Team Leaders and SAR Managers, supported by the P&Ts. Also, SARVAC is involved in a Humanitarian Work Force Program which will see GSAR volunteers assist P&Ts during emergencies and natural disasters.

In 2022 SARVAC officially rolled out the Legacy National Certification as part of Ground Search and Rescue National Accreditation and Certification.

Benefits SARVAC Provides to GSAR

- Insurance coverage is provided to all recognized GSAR volunteers and teams.

- Federal Search and Rescue Volunteer Tax Credit (approximately 3,000 Canadian Dollars).

- Service awards for members 25+ years active.

- SARVAC Core Competency and Curriculum Standards for Searcher, Team Leader, and Search Manager.

- GSAR Training Community website.

- SARVAC Basic Searcher eLearning program.

SARVAC Supports Adventure Smart (AS) Prevention Program

AdventureSmart is a national program dedicated to encouraging Canadians and visitors to Canada to “Get informed and go outdoors”. As part of this program, SARVAC provides in-person and virtual Trainer and Presenter training, outreach materials, liability insurance, and a stipend for presenters.

Over the past five years, SARVAC volunteers have provided 5,610 AdventureSmart presentations to 237,449 members of the public, contributing 31,532 volunteer hours (April 2021). This combines online and on-site awareness with targeted outreach in five programs – Hug a Tree and Survive, Survive Outside, Snow Safety & Education, Survive Outside-Snowmobile Safety, and PaddleSmart. AdventureSmart provides free web-based and mobile Trip Plan app, interactive kids’ game, comprehensive website, and eLearning training programs are under development.

SARVAC During Covid-19

The impact of Covid-19 determined the shift towards an online volunteering system developed by the Canadian Federal Government. In practice this meant changing to a programme where individuals conduct all tasks off-site (Lachance. 2020). The federal response was the establishment of the National Covid-19 Volunteer Recruitment Campaign. Developed in March-April 2020, it was based on the principles of: collaboration; evidence-informed decision-making; proportionality; flexibility; a precautionary approach; use of established practices and systems and ethical decision-making. Advertised on the Government of Canada jobs recruitment platform on 2nd April 2019, the volunteer opportunities involved:

- Covid-19 case tracking and contact tracing.

- Health system surge capacity.

- Covid-19 case data collection and reporting.

Within twenty days, 54,000 volunteers offered to help including Public Health students in Canada, who offered help with public health work during Covid-19 and assisted in case tracking and data collection (Jenei, 2020). As the pandemic evolved the Canadian Red Cross became a partner. The initiative was evaluated, and of the 10,768 participants who responded, the gender of applicants was 59% female, 35% male and 6% other. Survey responses from disabled people comprised 5%, ethnic minority groups 24% and Aboriginal 1%. Volunteer occupations were mostly in the health sciences and nurses, with similar numbers from the sciences, public health, management, and computer programming. The majority age group was the over 60s, however, findings from the 2015 Statistics Canada survey showed that respondents aged 24 and under comprised the second largest group. Emphasis had been placed on collaborating with provincial and territorial governments and international partners to minimise the economic, health and social impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Funding

SARVAC is funded 95% by the Federal Government Contribution Agreement, as well as by private and memorial donations and membership fees from P&T associations. Together SARVAC and P&T are able to access funds from SAR New Initiatives fund (SAR NIF), which is available for search and rescue projects. Applications are submitted annually, however there is no guarantee they will be funded as they are required to meet the Public Safety Canada program priorities.

In 2022 SARVAC received funding from the British Columbia Government for GSAR

– the first year in which the organisation has acquired sustainable provincial funding. Also, in 2022 SARVAC was awarded funding for a Humanitarian Workforce project that is ‘supporting a humanitarian workforce to respond to Covid-19 and other large-scale emergencies’.

Case Study 4: New Zealand, Community Emergency Hubs

Community Emergency Hubs in Wellington

A key issue for New Zealand is how spontaneous volunteers, such as those involved in Community Emergency Hubs, can be integrated officially with the Emergency Management structure. Community Emergency Hubs liaise with Emergency Management in a crisis; however, they are not integrated with the official response in terms of liability, vetting, training or health and safety. This challenge is not unique to New Zealand and raises a key concern that a lack of official integration can impact the effectiveness of Emergency Management. With a population of just over 5.1 million, statistics show that 21% of the population in New Zealand are involved in formal volunteering (Stats, N.Z. 2018). Approximately one fifth of the nation are integrated as official state volunteers with the North and South Island, as well as the 700 islands. One example of this is the New Zealand Red Cross, which works with disaster recovery (Wills & Cross, 2014) as well as training volunteer citizen translators (Federici & Cadwell, 2018). Notably informal spontaneous volunteering, which includes the example of Community Emergency Hubs in Wellington, are not officially integrated.

The New Zealand State of Volunteering Report (2020) recommends that volunteering be explored from multiple viewpoints. The report shows that the formal voluntary sector contributed 4 billion dollars to New Zealand’s economy, which is more than the construction industry. This figure is not a true reflection of the economic value of the voluntary sector given that informal spontaneous volunteering cannot be measured or quantified, because they are not officially integrated into the system. The four main recommendations from the 2020 report relate to the integration of the informal voluntary sector officially in the system.

Recommendations include:

- Community, diversion and inclusion.

- Engaging and recognising all volunteers.

- Funding, administration, and regulatory compliance.

- Management and strategy.

Together these address the challenge of integrating informal community groups and individual spontaneous volunteers into the system. Grant et al (2019) affirms that informal volunteering through spontaneous volunteer resources can evolve into formal structures. New Zealand seeks to reconcile an official response structured around command and control by integrating unofficial spontaneous volunteers, organised community groups, as well as unco-ordinated community response.

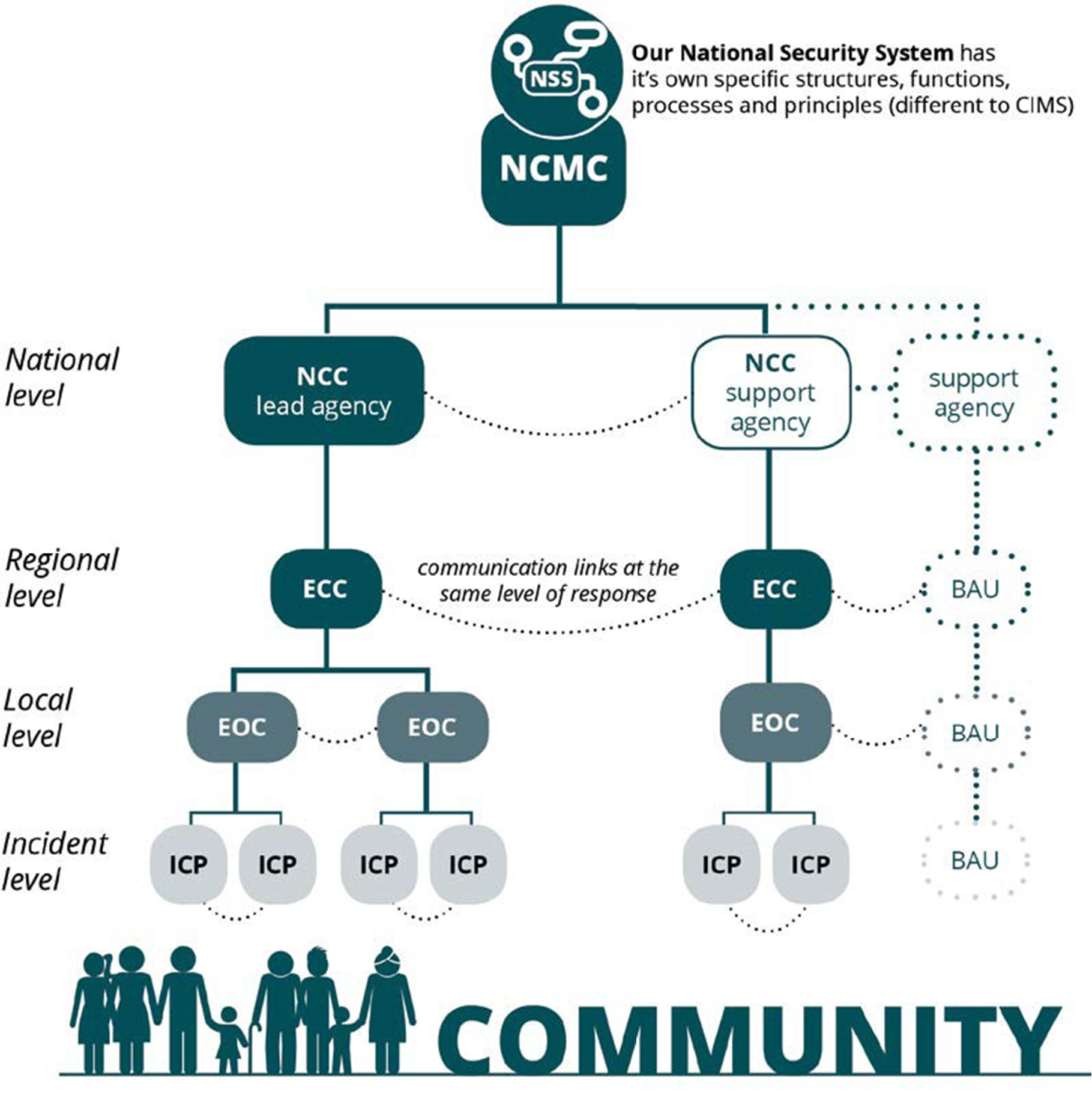

Currently New Zealand uses the Co-ordinated Incident Management System (CIMS) as the National Security Systems Model at all levels of response. The CIMS 3rd edition was launched in 2019 but does not show any clear links between the official response and the community unofficial response. The CIMS 3rd edition model is shown below.

The Community Emergency Hub Model in Wellington

- Currently there are 128 Community Emergency Hubs in the Wellington

- Wellington Region Emergency Management (WREMO) inherited the Civil Defence Centre model which was based around primary

- The concept of Community Emergency Hubs was developed through

- In 2017/2018 the Civil Defence Centres were renamed Community Emergency

- Hubs are mainly located in schools; however other venues include: resident associations; shops; a wildlife park; restaurants; a scout camp; a water treatment station and a library.

- The Hubs Model and Guide is freely

Development and Operation of Emergency Community Hubs

The development of Community Emergency Hubs emerged from the independent review of the Christchurch Earthquake (2011), which claimed 185 lives. Recognition of the role that spontaneous volunteers and community organisations have in responding to emergencies highlighted how this informal resource supported emergency management.

Hubs are established and operated by different communities in the Wellington region. They have authority to decide when and where to open a hub, and when to close it. A hub can be activated by an existing community group, a hub activation group, or by a hub without an organised group.

The hub utilises three components:

- A sign which shows the pre-determined location of the This includes physical signage that includes Google Maps as well as public information campaigns, and an online map located on getprepared.nz.

- A box which holds stationery supplies, maps and lanyards (but not civil defence supplies).

- A radio for volunteers to maintain a connection to the official They also have a phone, email address and provide online web-based information.

The Hub Instruction Guide

The Hub Guide contains five chapters of standard information about procedures. These include: accessing the hub: working as a team; setting up before you open; thinking about recovery. The fifth chapter contains guidance on the hub response plan including: resources; vulnerabilities; damage assessment and key challenges.

Tasks involve bringing members together before the hub has been activated so they can pre-plan. Planning entails identifying local resources, groups and networks of support. Planning also incorporates having knowledge and agreement about places and spaces where people could temporarily be given shelter, water, food and sanitation; as well as connecting with established services, such as medical assistance and business enterprise to develop a support infrastructure. Once opened local communities are requested to gather at the hub to hear the principles of the operation. The community task requires teamwork for sharing knowledge so everyone is aware of where the most vulnerable are located, enabling effective checks on people’s wellbeing and damage assessment.

Hub Roles

The Guide defines and explains eight recommended roles. These include:

- Hub Supervisor: the first role to fill.

- Reception: greets, provides general information and distributes lanyards.

- Needs and Offers: co-ordinates requests and offers of assistance.

- Public Information: variable but might mean updating a noticeboard outside the hub.

- Community Space (optional): cup of tea, psycho-social support

- Information co-ordination: discussion in private areas.

- Communication: communicates with emergency managers.

- Facility Maintenance: maintaining equipment.

Hub Responses to Emergencies

Official community emergency response teams can operate from a hub. The hub may also activate independently in response to a major event, such as an earthquake. Hubs may be operated by community groups, dedicated hub groups, or spontaneous volunteers. Communities also come together to resolve challenges with existing resources. The first response is directed to the household and then to immediate neighbours. Hub members decide the hours of operation, but hubs will not operate 24/7. The hub members may change location, if necessary, for example if school holidays have finished meaning school premises are no longer available. A high value is placed on ‘bonding’ within the hub group, which might include sharing values, interests and otherwise developing social capital.

Communication is established by linking to the official response of the Emergency Operations Centre to provide:

- Public information messaging.

- Situational awareness.

- Requests for assistance.

- Bridging with dissimilar/ hard to reach community groups.

Flood Example

The Southland floods of February 2020 was the first mass activation of hubs which was managed by 1,000 volunteers. A total of 26 hubs were activated to support thousands of evacuees, including residents and tourists. In excess of 4,400 people were evacuated from Gore, Mataura and Wyndham. In excess of 500 refugees were taken to Te Anua Hub. Lumsden hub received two buses of stranded tourists and Mataura hub provided food and essentials to returning residents.

Covid-19

With a total of 1.95 million cases, there were over 2,000 deaths from Covid-19 in New Zealand. Wellington City Council provided a helpline, facebook communication and map information through their website, covid19.govt.nz. The National Response of New Zealand to Covid-19, which finished in September 2022, involved a system based on traffic lights, red, orange and green, which set out boundaries for peoples’ behaviours (Fletcher, 2022). Official volunteers included Age Concern, which supported the over 65s. They also advertised how citizens could contact their local community centres, for example, or organisations such as the Salvation Army, St Vincent de Paul, and other formal volunteer associations. Police vetted all volunteers from the Greater Wellington area. They also asked for all volunteer and community organisations to register online. Community Hubs liaised with Emergency Management but were not officially integrated.

Community Hub Community Examples

Blue Mountains Residents’ Association was active in the community prior to Covid-19. Preparing for Covid-19 community cases involved connection and communication with Emergency Management. Although the official Covid-19 response was not run by Emergency Management they used the hub kit when needed.

Manor Park hub participated in a preparedness workshop on Covid -19 and subsequently held a hub drill initially in a garage until a local shop was offered as a hub location (the offer coming about through connections with the local council and local Mayor). The preparation for Covid-19 involved delivering food, prescriptions and Covid-19 testing kits, as well as lawn mowing.

Positively Pacific Group activated and operated a hub in February 2021 and used it to provide food for the spontaneous community response to Covid-19, which was linked into the emergency manager’s official response. Communities have also recognised the benefits of official integration.

Community Response to Community Emergency Hubs Integration with the Official Response

- Hubs can add capability to existing community groups and the official response through their structure, connection and communication for an emergency response.

- Hub groups can expand into other areas to serve the community.

- Hubs can maintain communication with official agencies.

- Emergent groups, such as the Student Volunteer Army are highly skilled, for example in social media, and can support the official response, particularly during and post impact of emergencies.

References

Bruey, A., 2018. Bread, justice, and liberty: Grassroots activism and human rights in Pinochet’s Chile. University of Wisconsin Pres.

Bryer, T.A., Pliscoff, C., Lough, B.J., Obadare, E. and Smith, D.H., 2016. Stipended national service volunteering. In The Palgrave handbook of volunteering, civic participation, and nonprofit associations (pp. 259-274). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Carr, J.A., 2014. Pre-disaster integration of community emergency response teams within local emergency management systems. North Dakota State University

Canada National Covid-19 Volunteer Recruitment Campaign – Horizontal Lessons Learned Review https://www.canada.ca/en/public-service- commission/services/publications.html

Espinoza, A.E., Osorio-Parraguez, P. and Quiroga, E.P., 2019. Preventing mental health risks in volunteers in disaster contexts: The case of the Villarrica Volcano eruption, Chile. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 34, pp.154-164.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), US Department of Homeland Security, and United States of America. “Are You Ready? A Guide to Citizen Preparedness.” (2002).

Federici, F.M. and Cadwell, P., 2018. Training citizen translators: Design and delivery of bespoke training on the fundamentals of translation for New Zealand Red Cross. Translation Spaces, 7(1), pp.20-43.

Fletcher, M., 2022, June. XVI. Government’s Social and Economic Protection Responses to Covid-19 in the Context of an Elimination Strategy: The New Zealand Example. In Protecting Livelihoods (pp. 361-376). Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG.

Flint, C. and Brennan, M., 2006. Community emergency response teams: From disaster responders to community builders. Rural Realities, 1(3), pp.1-9.

Flizikowski, A., Holubowicz, W., Stachowicz, A., Hokkanen, L., Kurki, T.A., Päivinen, N. and Delavallade, T., 2014, May. Social media in crisis management-The iSAR+ project survey. In ISCRAM conference.

Grant, A., Hart, M. and Langer, E.R., 2019. Integrating volunteering cultures in New Zealand’s multi-hazard environment. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, The, 34(3), pp.52-59.

Gray, B., Colling, M. and Michaud, S., 2021. Supporting Emergency Health Services during a Pandemic: Lessons from the Canadian Red Cross. In 18th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, ISCRAM 2021 (pp. 320-332).

Jenei, K., Cassidy-Matthews, C., Virk, P., Lulie, B. and Closson, K., 2020. Challenges and opportunities for graduate students in public health during the Covid-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 111(3), pp.408-409.

Lachance, E.L., 2020. Covid-19 and its impact on volunteering: Moving towards virtual volunteering. Leisure Sciences, 43(1-2), pp.104-110. Leroux, J.G., 2018. Canadian Search and Rescue Puzzle: The Missing Pieces. Canadian Military Journal • Vol. 18, No. 2, Spring 2018

Mackwani, Z. and Cross, C.R., 2016. Assessment of the Canadian Voluntary Sector Capabilities and Capacity in Emergency Management. Canadian Red Cross Contract Report.

Masten, A.S. and Motti-Stefanidi, F., 2020. Multisystem resilience for children and youth in disaster: Reflections in the context of Covid-19. Adversity and resilience science, 1(2), pp.95-106.

Muñoz-Navarro, A., 2009. Youth and human rights in Chile. Youth Engaging with the World: Media, Communication, and Social Change, pp.43-60.

Nakamura, J.S., Lee, M.T., Chen, F.S., Archer Lee, Y., Fried, L.P., VanderWeele, T.J. and Kim, E.S., 2022. Identifying pathways to increased volunteering in older US adults. Scientific reports, 12(1), pp.1-16.

Nesbit, R. and Brudney, J.L., 2013. Projections and policies for volunteer programs: The implications of the Serve America Act for volunteer diversity and management. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 24(1), pp.3-21.

Saaristo, P. and Aloudat, T., 2011. (A4) Emergency Health Interventions in Earthquakes: Red Cross Experience from Haiti and Chile, 2010. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 26(S1), pp.s2-s2.

Shelby, T., Hennein, R., Schenck, C., Clark, K., Meyer, A.J., Goodwin, J., Weeks, B., Bond, M., Niccolai, L., Davis, J.L. and Grau, L.E., 2021. Implementation of a volunteer contact tracing program for Covid-19 in the United States: A qualitative focus group study. PloS one, 16(5), p.e0251033.

Stewart, K., 2018. An Overview of the CERT Resilience Management Model (CERT-RMM). Carnegie Mellon University Software Engineering Institute,