Independent Review of the 2004 Civil Contingencies Act

About this report

Published on: March 24, 2022

We were asked by the National Preparedness Commission: “To review the implementation and operation of the Civil Contingencies Act 2004, of the civil protection structures it introduced and its associated Regulations, guidance and key supporting enablers; and to make recommendations for improvements.”

This scope deliberately covered not only the content of the Civil Contingencies Act (‘the Act’) itself but also the supporting arrangements which give it real-life effect, on the ground, in delivering the intent of the UK Government and the UK Parliament. This report therefore intentionally has an operational focus.

Authors

Bruce Mann CB

Kathy Settle

Andy Towler

Executive Summary

Our Scope and Approach

We were asked by the National Preparedness Commission:

“To review the implementation and operation of the Civil Contingencies Act 2004, of the civil protection structures it introduced and its associated Regulations, guidance and key supporting enablers; and to make recommendations for improvements.”1

This scope deliberately covered not only the content of the Civil Contingencies Act (‘the Act’) itself but also the supporting arrangements which give it real-life effect, on the ground, in delivering the intent of the UK Government and the UK Parliament. This report therefore intentionally has an operational focus.

In the same operational vein, we have also sought to build on experience and learning. The UK has experienced a wide range of emergencies over the last 20 years and gained a rich body of learning. So a major focus of our work was discussions with those on the front line – statutory bodies in England and Scotland, including inputs from all 38 English Local Resilience Forums; The Executive Office in Northern Ireland; regulated utilities with duties under the Act; businesses; voluntary and community groups; and dedicated individuals – to gather their operational experience of delivering the Act and its intentions, and of preparing for and responding to emergencies. We also gained valuable insights from discussions with a wide range of other bodies including Parliamentarians, Councillors, the National Audit Office and Information Commissioner’s Office, regulators and inspectorates, sector representative bodies, practitioners from other countries, the BBC, consultancies and higher education institutions. In total, we conducted 130 interviews with some 300 people. We also received 29 written submissions and 31 other pieces of evidence.

We have been inspired by the way in which so many people gave up so much of their time to contribute their experience and ideas for improvement – and by the passion and commitment they showed to making those improvements. That gave us great hope for the future. We wish to extend our thanks to everyone who contributed at a time when they were under great pressure.

Fit For the Present? Fit For the Future?

We shaped our work around two fundamental questions.

First, drawing on the evidence we received and other research, we reviewed the way in which UK resilience arrangements have developed since 2004, to enable us to reach a judgement on where resilience in the UK stands today and whether the original intent of the UK Government and the UK Parliament has been met.

Second, we reviewed whether the Act and its supporting arrangements would provide a solid legal and operational platform for building and sustaining the resilience of the UK over the next 20 years. We did so against the UK Government’s ambition to “make the UK the most resilient nation”2.

Before reaching conclusions, we went back to the fundamentals. The world has changed over the past 20 years. So has business, the economy and society. They will change much further over the next 20 years. In particular, the risk picture the UK faces is less benign now than in 2004 and is likely to get worse.

So what should we be seeking to achieve in building UK resilience over the next 20 years, to address the challenges the UK is likely to face and the characteristics, attitudes and expectations of society? Who should be involved? Specifically, who should have legal duties? Which legal duties are relevant today, and in the future world? And what structures are needed to bring together the actions of the wide range of organisations and people – at national, regional and local levels, across the public, private and voluntary sectors, and in communities – into a cohesive whole in support of the shared endeavour of avoiding or minimising harm and disruption.

Although machinery and process are important, people are everything. Skilled, competent and confident people are the foundation of effective risk and emergency management. So we had a key focus on the pursuit of excellence. Are the skills and competences needed – by individuals and teams – well-defined? Do those involved have the level of skills and training they need to do a good job? What arrangements are in place to check that people do indeed have the skills they need and can demonstrate their competence, especially in the management of major emergencies?

And more broadly, what are the systemic arrangements for sustaining excellence in all resilience-building activities? What quality standards have been set? How are they applied? What are the arrangements to provide validation and assurance of the work done, at all levels? Do senior leaders of Resilience Partnerships3 have a good picture of the quality of the work of the Partnership? Does the Government have a good picture of the quality of resilience in the UK overall? Are the accountabilities of senior leaders clear? And are the arrangements in place for supporting political oversight and scrutiny mechanisms adequate?

Our Findings

The Act and the transformed resilience arrangements it introduced were a vital step down the road to building a Resilient Nation. They have served the UK well over the past 18 years. They provide a sound basic framework for emergency preparedness, response and recovery. And we were impressed by the quality of what local statutory bodies and Resilience Partnerships have delivered and are seeking to achieve in future, despite very limited levels of resourcing.

But the pace of development has not been sustained over the past decade. In some important areas, quality has degraded. As a result, UK resilience today has some serious weaknesses. It is not fit for future purpose in the world the UK is moving into.

The lack of development in the resilience field is in sharp contrast to the continuing positive development in other national security fields, especially cyber security and counter- terrorism, which was warmly commended by many of those we spoke to. It is also in sharp contrast to the progress made by a wide range of other countries over that time to build their risk and emergency management systems. Resilience in the UK has suffered strategic neglect. As the National Audit Office has observed:

“… [the] government’s operational management capability has changed little over the past 10 years. Government has often operated in a firefighting mode, reacting in an unplanned way to problems as they arise and surviving from day to day. Our evidence suggests that a fundamental shift in capability, capacity and resilience may be needed to cope better with future emergency responses.”4

Recovery will need action at two levels. First, there is a need to improve the quality and sustainability of current arrangements. Then we believe that there will be a need to undertake a further transformation, on broadly the same scale as that made after 2004, if UK resilience is to be fit for the future the UK faces – and to match the ambition that the UK is a truly Resilient Nation.

Our most significant diagnostics and recommendations5 for the actions that should be taken are set out below, in seven key areas which form the structure of our main report. None are new. They cover areas where resilience capability and capacity has degraded over the past decade, projects which have been started but have not progressed, good practice in other national security sectors which can be imported, programmes which are being pursued in some localities on their own initiative and which could be implemented more widely, or good practice in other leading countries which could readily be adopted by the UK.

Given the comparative lack of development of UK resilience over the last decade, our recommendations cover not only areas for direct improvement but also proposals for building in continuous improvement and the pursuit of excellence – and validation and assurance, accountability and political scrutiny arrangements which detect and arrest drift and decay.

Some of our recommendations are capable of being implemented quickly. Others will take time, especially as some will require new or amended legislation. And some will require modest investment: we estimate the aggregate cost were all our recommendations to be fully implemented at some £30-35m per year including contingency6.

Recognising the need to prioritise, we have set all of our recommendations against six tests of operational- and cost-effectiveness:

- They would make a material contribution to building a more Resilient Nation, one which properly protects the safety and wellbeing of its citizens, its economic development and the environment.

- They would in particular make a substantial contribution to the management of future ‘catastrophic’ emergencies with national or wide-scale consequences.

- They would embed arrangements which provide clarity on what good looks like, and enable the identification for scrutiny and action of areas where quality was weak or degrading so that improvement action was needed.

- They are what the public and Parliament would reasonably expect.

- If extra resourcing would be required, the investment would be reasonable and proportionate to the operational value gained.

- They are practicable and deliverable.

We have used our discussions with statutory bodies, businesses, and voluntary and community groups not only to gather their experience and ideas for improvements but also to test with them the practicality and deliverability of our proposals. We have been struck – and inspired – by the consistency of view across front-line organisations about the improvements needed, and by the ambition we have heard for future resilience in the UK. On the basis of those discussions, we believe that all of our recommendations would make a significant contribution to effective risk and emergency management in the UK. And we believe them to be deliverable, if the political will is there.

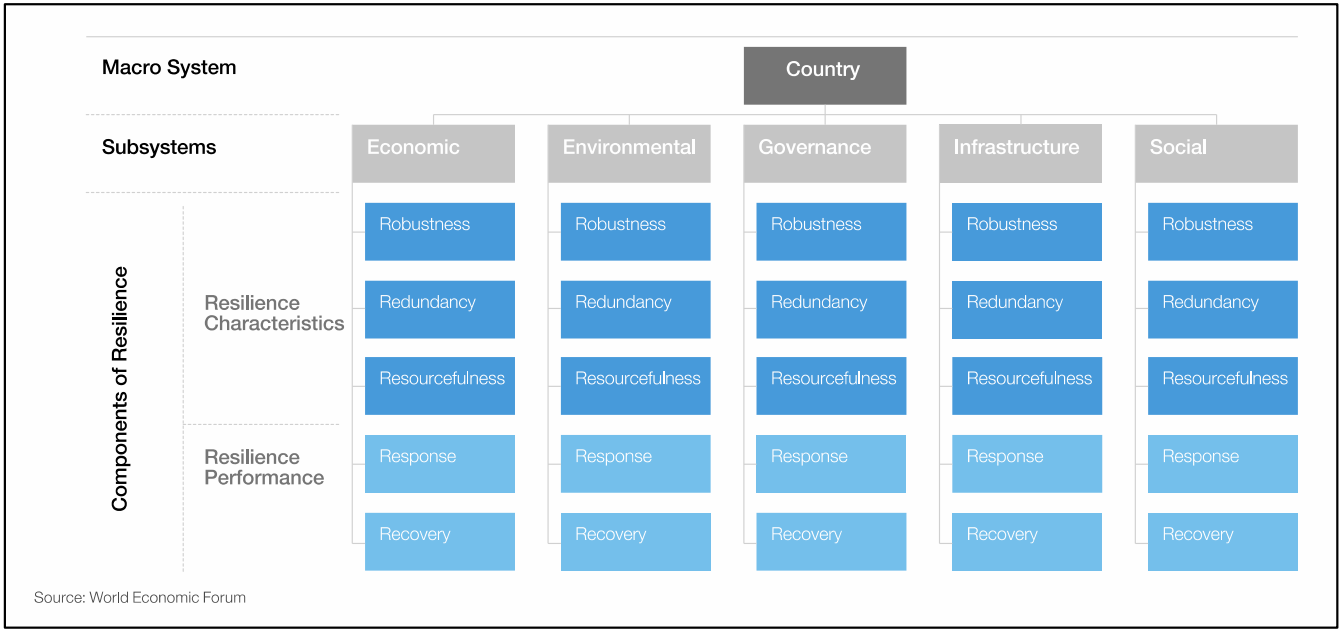

What is Resilience and a Truly Resilient Nation?

The current scope of ‘Resilience’ in the UK covers only part of the job. It has insufficient emphasis on preventing emergencies arising in the first place or at least reducing their likelihood, or of proactively designing resilience in to all aspects of our society and economy. The past 20 years has seen the development of international agreements – especially the Hyogo and Sendai Frameworks7 – and good practice in international bodies and in leading countries in developing risk reduction policies and programmes. But with some welcome exceptions, especially on climate change, current legislation, policy and operational practice covering the building of UK resilience remains focused on emergency preparedness, response and recovery.

A number of Resilience Partnerships have undertaken their own local risk reduction activities over many years, operating outside the terms of the Act. More recently, Resilience Partnerships have been asked by the UK Government to undertake risk reduction work in tackling supply chain and other issues which had the potential to cause serious harm and disruption. And there has been inspiring work in some parts of the UK – especially London, Greater Manchester and Hampshire – to build ‘Resilient Places’, using policies with a medium- and long-term horizon to tackle vulnerabilities, reduce the risk of emergencies arising and ‘design resilience in’. But those remain glorious exceptions, not promoted or pursued more widely. And there has until now been no systematic work to build the strategic resilience of the UK overall.

We recommend that risk reduction activities should be put onto the same legal and operational basis as emergency preparedness, response and recovery. The resulting new resilience framework for the UK should be fully aligned with the Sendai Framework. That should include putting in place mechanisms to gather the metrics recommended by the Sendai Framework to allow progress in building UK resilience to be tracked. We hope that the forthcoming Resilience Strategy will reflect that intention.

All Resilience Partnerships we spoke to would welcome the expansion of their work into this area. We believe that doing so would be feasible and cost effective, subject to:

- The scope being clearly defined

- Boundaries being placed around the new activity so that they do not become absorbed with tackling longstanding chronic issues in public service delivery

- The collaborative definition with the UK Government of expectations on how the new role should be delivered

- Sufficient resourcing

Therefore, we recommend that an amended Act or future legislation should include a new duty on risk reduction and prevention. Its execution should be covered in new, dedicated statutory and non-statutory guidance. And new arrangements, including fuller government support to Resilience Partnerships, should be put in place to encourage and support localities in the development of Local Resilience Strategies which seek to build deeper societal resilience across the medium- and long-term. The role of Resilience Partnerships in leading or providing substantial support to the development of Local Resilience Strategies should be recognised in statutory guidance.

Who Should Be Involved in Building UK Resilience?

Current resilience-building arrangements in the UK fully involve only some of those who could contribute, mainly confined to local statutory bodies, some government agencies and the regulated utilities. Arrangements for involving the voluntary sector do not fully recognise or capture the contribution they can make. Arrangements for involving the business sector are weak. And, despite good work over more than a decade on enabling communities to build their own resilience, Resilience Partnerships are struggling to make significant progress.

The Act, in creating new duties and structures rooted in the public sector, tackled the easier part of building UK resilience. The harder part – of engaging the ‘whole of society’ – remains more said than done. Yet the response to the COVID-19 pandemic showed once again what has been seen in previous major emergencies: the huge appetite and willingness on the part of individuals, communities, voluntary organisations and businesses to make a contribution – of time, money and materials – and how powerful that contribution can be when harnessed.

We propose three guiding principles for new arrangements which move the phrase

‘whole of society’ from being a cliché into having real operational meaning:

- ‘Putting People First’ – extending emergency planning as a matter of routine into the identification of the consequences for people, taking account of the different vulnerabilities of different groups in each area, to provide the basis for developing a fuller and more detailed assessment of their potential needs. Needs-based planning will provide a basis for dialogue about how best to meet those needs and who is best placed to do so, whether from statutory bodies, businesses or groups in the voluntary and community sector (VCS). In particular, it would enable the involvement of a wider range of local organisations in building local And it would provide a focus in emergency planning for the populations most vulnerable to, and most disproportionately affected by, the consequences of emergencies because of their income, geography or other characteristics.

- Proper planning and preparation. This can build on good work in some Resilience Partnerships to develop arrangements for capturing the contribution which VCS organisations, businesses and communities might make, and integrating that activity with the response of statutory bodies into a cohesive response framework, ensuring that important safeguards are met and that contributors are trained and plans are tested in exercises involving the organisations concerned.

- Undertaking this work in a spirit of genuine partnership, most often judged through actions rather than words.

This revised approach would require the revision of current statutory guidance on emergency planning. But the changes needed properly to involve the whole of society go much wider.

For the VCS, we believe that the current ‘have regard to’ formula covering their involvement in resilience-building activity is not working and should be abolished. The response to the COVID-19 pandemic has shown once again the powerful contribution that local and national VCS organisations can make, including the ability to draw on their networks for knowledge and insights which can be used in the development of plans; important assets and capabilities; and, in many cases, the delivery of support to those directly or indirectly affected by an emergency. VCS organisations should have true partnership status in the resilience-building activities of local bodies, Resilience Partnerships and central government departments. This should be based on arrangements which provide clarity about which VCS organisations will provide which skills and capabilities in what circumstances, and confidence that those skills and capabilities can be mobilised quickly and effectively if necessary and integrated cohesively into the emergency response. It should also include arrangements for joint training and exercising where relevant. Engagement of the VCS should be captured in a new Resilience Standard.

The full involvement of business is another fundamental plank of the whole of society approach to building UK resilience. And yet, the vast majority of the businesses and business representative organisations we interviewed had had almost no engagement with UK Government on resilience matters in the years before the pandemic. Many observed that levels of engagement had declined sharply from those of a decade ago, although for most the position improved during the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a strong sense of the UK Government viewing engagement as something that ‘needed to be done’.

This showed in the clear perception of there being an absence of thinking in government about the needs of business in resilience planning, let alone a readiness to give business a voice. As a result, there was a widely-held view that the government did not have a good understanding of business resilience, especially the resilience of supply chains. Even in cases where businesses had sought advice, several felt that the government did not wish to listen or engage.

The absence of routine engagement on resilience matters between government and business at national level was well behind access and engagement arrangements in other national security fields, which were widely praised. There was a widely-held view that more and better progress had been made on building a whole of society approach to addressing physical and cyber security threats than on building resilience.

Filling this gap is vital. And the appetite for greater levels of engagement is there, provided that it is attractive – properly managed, value-adding and operationally-focused – rather than a ‘talking shop’. The aim should be to improve the precision and quality of planning on both sides, thereby creating greater certainty where at present there is uncertainty. To achieve this, we believe that the relationship between the UK Government and business on resilience matters should be placed on a formal partnership footing with the creation of a Business Sector Resilience Partnership, with wide participation, supported by a dedicated team in the Civil Contingencies Secretariat. This would supplement existing business engagement arrangements managed by individual government departments within their sectors, and focus on national risks with wide-scale consequences and common and cross- cutting issues. Its work should be operationally-focused, and cover the assessment of risks and their consequences, risk reduction, the mitigations which might be put in place to address the impacts of emergencies on businesses, and the contribution which businesses might make in the response to major emergencies. A key feature of the new arrangements should be the greater visibility and approachability of officials towards the business sector.

Two early priorities for the work of the Partnership should be:

- The involvement of businesses in risk assessment, drawing on their knowledge and expertise; and the co-development of information and advice on risks, consequences and plans targeted on meeting the planning needs of businesses

- Capturing the contribution which businesses are ready to make to the response to a major emergency

The new arrangements should be set out in a new chapter in statutory guidance dedicated to business involvement in building the resilience of the UK. And engagement of the business sector in resilience-building should be captured in a new Resilience Standard.

There has been good developmental work over more than a decade on community resilience. Some areas are making good progress: some of the tools and techniques they have developed are good practice. And the recent creation of the National Consortium for Societal Resilience [UK+] involving over 60 bodies to support and enable future progress is very encouraging. But, despite this promise, many Resilience Partnerships are struggling. So we sought to identify where the blockers to progress lay, and what could be done to accelerate progress.

We judge that the development work has borne fruit: the most suitable approaches to involving and empowering communities are understood and being adopted. Some limited but important work is needed to provide Resilience Partnerships with the tools, templates and other resources they need. We recommend that the UK Government should pursue, including with the National Consortium, how Resilience Partnerships can be provided with practical hands-on peer support and advice to help them adapt and implement tried and tested approaches in their areas. And there would be significant benefits in integrating community resilience activity into multi-agency training and exercising.

It is clear that the major blockages are resourcing, and the commitment of senior leaders in local bodies and UK Government to making progress. On the former, we recommend the creation of a Community Resilience Co-ordinator post in each Resilience Partnership dedicated to the engagement of VCS organisations, businesses and communities. On the latter, after detailed discussion with Resilience Partnerships, we recommend that an amended Act or future legislation should include a new duty requiring designated local and national bodies to promote and support community resilience. The new arrangements should be captured in associated Regulations and a new dedicated chapter in statutory guidance. And the current Resilience Standard should be updated.

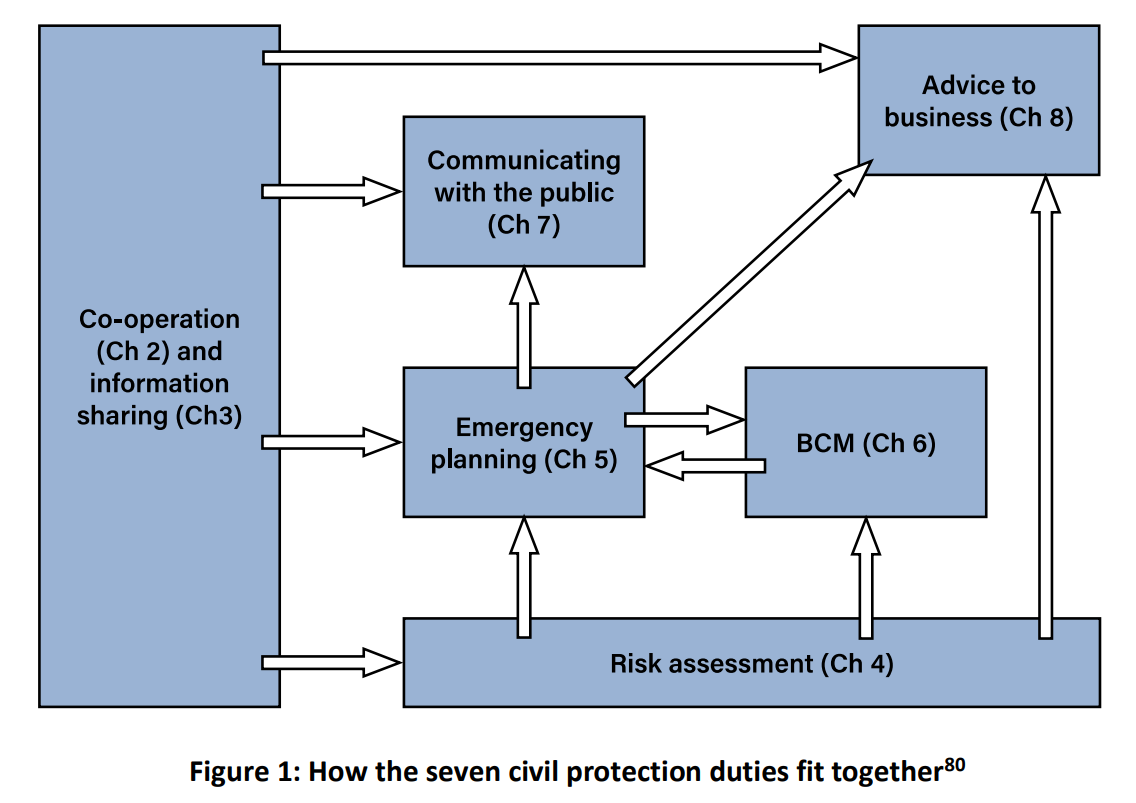

Duties Under the Current Civil Contingencies Act

The current duties in the Act remain broadly fit for purpose, subject to some updating, and with the extension of the emergency planning duty to support needs-based planning as described above.

But there is a pressing need to modernise some duties and substantially improve arrangements for their execution.

Risk Assessment

Too much time and energy is spent on risk assessment processes which can be better devoted to improving the quality and depth8 of analysis. The whole risk assessment process needs to be radically re-imagined, simplified and digitised, in close consultation with Resilience Partnerships. That will create capacity for much needed improvements. In particular, we believe that the recent move to focus on only a two-year time horizon in the National Security Risk Assessment (NSRA) is a mistake which should be reversed. A two-year horizon does not provide a sound platform for planning and capability-building for emerging societal hazards, especially those with complex cascading and compounding effects across multiple sectors. It does not address chronic risks which might worsen over time and reach a tipping point where the impacts become intolerable. And it does not provide an adequate basis for the work on Local Resilience Strategies we describe above. We recommend that risk assessment should be returned to the previous practice of having separate assessments that look ahead for five years and twenty years respectively, to enable longer-term prevention and preparedness activity.

New arrangements also need to embed concurrency, reflecting the changing future risk picture. And they need to provide for greater agility. We hope that the UK Government will use the new Situation Centre in the Cabinet Office as the hub of a network providing relevant, rapid and dynamic analysis of emerging and changing risks not only to UK Government departments but also to Resilience Partnerships and the Devolved Administrations.

The understandable need to protect genuinely sensitive information has been allowed to mushroom so that it has become an unnecessary barrier to sharing information in the National Security Risk Assessment (NSRA) and hence to resilience-building activity in Resilience Partnerships. This could be substantially fixed by simple process improvements – the classification of individual passages; and the inclusion of handling guidance within the NSRA – which should be pursued as a matter of urgency.

Public Awareness Raising

The duty in the Act to raise public awareness on risks, consequences and emergency plans is being met in only the most tokenistic way, substantially reducing the effectiveness of resilience activities across the business and voluntary sectors and in communities. In part, that stems from the provisions of statutory guidance which limits the information which

Resilience Partnerships are required to publish to only Community Risk Registers. Much more could and should be published. There is also a widespread perception of the cultural reluctance of UK Government to share information widely with the public, even on hazards where there are few, if any, national security sensitivities. This is in sharp contrast to the way in which the provision of public information has been tackled in the cyber security and counter-terrorism fields, which was widely commended by those we spoke to for finding the right balance between publication and protection of information.

We believe that the current culture needs to be turned on its head – there should be a presumption of publication of material on risks and their consequences, including that in the National Security Risk Assessment, and on national and local emergency plans, unless there are clear and justifiable national security or commercial reasons not to do so. We make detailed proposals in our main report for the public information actions that need to be taken.

Information Sharing: The Sharing of Personal Data

We received compelling evidence from public, private and voluntary sector organisations of the way in which actual or perceived restrictions on the ability of organisations to share personal data meant that those affected by emergencies, especially the COVID-19 pandemic, had not received support which was as effective or as timely as it should have been.

This is not a new issue. It arose in the immediate aftermath of the 2005 London bombings, after which the UK Government published guidance setting out a number of key principles to guide emergency planners and responders in their decision-making on information sharing. That has been superseded by more recent guidance issued by the Information

Commissioner’s Office on the principles to be used in decisions on data-sharing in emergencies. But the organisations we interviewed felt strongly that legal restrictions in primary law on the sharing of personal data trumped guidance with non-statutory force. This was especially the case in circumstances where decisions on the sharing of personal data were being made by relatively junior staff in highly-pressured circumstances. Many made the argument that the absence of an explicit exemption in the Data Protection Act 2018 for the sharing of data in such circumstances reinforced the presumption against sharing.

Although there would be value in better training on the new guidance, and in the development and use of Priority Service Registers, we do not believe that they will meet the humanitarian need. The uniform view of interviewees was that the sharing of data in an emergency should be covered by a specific exemption in the 2018 Data Protection Act, capable of being used quickly and with confidence by operational staff facing the urgent

demands of meeting people’s needs. We share that view and believe that a further exemption in the Data Protection Act should be created which allows for the sharing of personal data in cases of ‘urgent humanitarian necessity’. This formulation is intended to provide a legal ‘triple lock’ against misuse of the exemption. Those citing the exemption in the formal recording of their decision to share personal data in the response to an emergency would be required to demonstrate that the need to do so was:

- Urgent, as would be the case in an emergency;

- Intended to meet identified humanitarian need, most likely by reference to the identified or anticipated consequences of the emergency for the physical or mental well-being of those affected; and

- Necessary, to enable the provision of support which would not otherwise be provided, or of support where the actions of two or more agencies working together would result in a material difference to the quality or timeliness of the support provided.

An ideal opportunity exists to pursue this change as part of reforms to the UK’s data protection regime on which the UK Government has recently consulted.

Business Continuity Promotion

The duty on local authorities to promote business continuity is of a past age and should be abolished. The objective of seeking to improve the resilience of businesses and voluntary organisations remains worthwhile. But the best means of promoting organisational resilience needs to be rethought from first principles, including the standard to be promoted, the audiences that are best placed to receive and act on advice, the wide range of channels (including government bodies) for reaching those audiences, and the most efficient and consistent way of providing advice across those channels.

Who Should Have Duties?

There is limited need for change to the list of those bodies with the full suite of duties

placed upon them (the so-called ‘Category 1 responders’).

Despite best intentions in 2004, it is clear that the distinction made in the Act between statutory bodies with the full suite of duties and the much lighter set of duties placed on the regulated utilities and others (‘Category 2 responders’) no longer works. The involvement of Category 2 responders in the risk assessment, emergency planning and public communications work of Resilience Partnerships is vital, especially against the future risk perspective. But, although engagement by some utility sectors remains good, in others it has eroded over time, with damaging impacts on the quality of risk assessments and emergency planning and hence the response to emergencies. And there is a clear and growing sense that Category 2 responders are ‘second-class citizens’, eroding the sense of partnership on which resilience depends. We believe that their full engagement is best achieved by their designation with the full range of duties in the Act. We recognise the additional costs this will entail, but judge these to be small and heavily outweighed by the benefits for public safety which will be achieved. The administrative burden could, however, be reduced by engaging Category 2 responders at regional level; mutual cross-working, where one company effectively represents the interests of others in the sector; and the greater use of virtual attendance at meetings.

The Joint Committee which reviewed the Civil Contingencies Bill in 20039 recommended placing duties on the UK Government and the Devolved Administrations as well as local bodies, to create a clear national civil contingencies framework. The then Government rejected that recommendation. Experience since 2004, and especially over the past decade, has shown that decision to be fundamentally wrong.

Effective resilience must be a shared endeavour. As recent experience has shown, UK Government departments have to carry their share of the load and have vital leadership, operational and enabling roles to fulfil. We heard powerful evidence of weaknesses in the discharge by UK Government departments of their responsibilities during the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. And many interviewees brought out the inherent double standard of the model of ‘do as we say, not as we do’. We recommend that the full suite of duties should be placed on the UK Government, and that Regulations and statutory guidance should provide a clear definition of the roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of relevant departments and agencies in the implementation of those duties.

Structures

Resilience Partnerships

The basic governance and collaboration structures introduced by the Act, founded in Resilience Partnerships at local level, remain a sound platform for the future although, drawing on experience, we would suggest that there would be value in the Scottish Government reviewing the roles and responsibilities of Partnerships in Scotland at local, regional and national levels, drawing on learning across the four UK Nations.

We have considered whether Partnerships should be given legal status but believe that doing so would risk legal confusion in an area where clarity is vital, erode the vital spirit of partnership on which resilience-building depends, and bring added cost and bureaucracy, and thus be counter-productive. But there is a need to give the Chairs of Resilience Partnerships ‘teeth’ in tackling under-performing organisations which are clearly not fulfilling their responsibilities. Some of this will come through tighter arrangements for the validation of performance and for bringing home the personal accountability of senior leaders which we cover below. But stronger arrangements for administrative escalation to, and timely intervention and enforcement by, the UK Government are clearly needed. It was disappointing to hear that, in those rare circumstances where local persuasion had not worked, the Chairs of the Partnerships involved had rarely felt able to escalate issues with under-performance to the relevant national authorities and that, where they had done so, the relevant UK Government department had conspicuously taken no action.

The recommendation above that resilience-building activities in the UK should in future cover risk reduction and prevention would in itself represent a substantial broadening of the role and workload of local bodies and Resilience Partnerships. But we believe that future governance and collaboration structures need also to reflect three further significant shifts.

First, a future risk picture which is markedly worse than in 2004 when the structures in use today were established. Resilience Partnerships will need in future to be capable of planning for and managing more emergencies on a national scale; more emergencies with cascading and compounding effects, with more wide-spread consequences for people’s wellbeing and way of life; and more concurrent emergencies.

Second, moving from the current rhetoric to an effective whole of society architecture for building resilience in the UK on the lines we propose above will need good, local leadership by public bodies working collectively.

Third, the expectations of the UK Government, which has over the last five years significantly shifted its expectations and use of English Local Resilience Forums (LRFs). One part of the shift has seen the greater engagement of LRFs in risk reduction and prevention activities. A second has been that the UK Government is increasingly looking to LRFs to act as a single collective, to receive and undertake tasks set by the UK Government and to report back as an entity.

These changes mean that Resilience Partnerships are in a fundamentally different position to that envisaged in 2004 and set out in Regulations and guidance. We therefore discussed with local bodies and Resilience Partnerships whether current structures remain the best vehicle for building future UK resilience. It is notable that the almost unanimous view of those we interviewed was that current structures on the current geography are fit for future purpose, and that continuity – of securing and then building on what has been achieved over the past 20 years – is important. We share that view. But if local bodies and the governance structures within which they operate are to be capable of fulfilling this wider and more challenging role, they need clarity about their future role and the expectations on them. And they need the tools to do a bigger job.

We recommend that the UK Government should as an early priority discuss and agree with Devolved Administrations and English LRFs a formal document which sets out the future role of local bodies and of Resilience Partnerships, and expectations on the way in which they will discharge that role. It should subsequently reflect the revised framework in an amended Act or future legislation, associated Regulations and supporting statutory and non- statutory guidance.

Designated local bodies and Resilience Partnerships are operating at levels of resourcing which are unsustainable even for achieving today’s ambitions, with significant impacts on staffing, skills development, and training and exercising which are causing real damage to their operational effectiveness. Current resourcing levels are insufficient to deliver existing policy let alone the additional tasks that come with the ambition of the UK being the most Resilient Nation. The key resource deficiencies which need to be addressed are at the heart of the work of the Partnership itself. We have identified five posts10 which are central to enabling a Partnership to fulfil its current and future roles, addressing the systemic weaknesses we identify in this report and taking on the new tasks we recommend.

But having the people is not enough. Clearly, they need to be trained, competent and confident in their roles. Much of this will lie with individual organisations. But there is one area – multi-agency exercising – where collective funding is needed, where the training is vital to operational effectiveness but where the impact of budget reductions over the past decade means that insufficient training has been undertaken.

We judge that the sustainable long-term funding package provided by the UK Government to English LRFs11 should cover as a minimum the costs of the five core posts identified above plus one major multi-agency exercise per year in each LRF. This should be provided by the UK Government as either ring-fenced funding or specific grant, so that the sums available are visible to all partners. The UK Government should also fund the consequential increases to settlements for the Devolved Administrations. The UK Government should also develop and publish a standard funding formula for the top-up contributions made by those bodies designated as Category 1 responders under the Act. It should be based on the partnership principle that all Category 1 responders contribute their fair share calculated under the funding formula.

Metro Mayors

The Act, its associated Regulations and supporting guidance are silent on the role of Metro Mayors of combined authorities in local resilience-building activity. That is unsurprising, given the relative newness of devolution settlements. But Metro Mayors are here to stay and have a valuable role which needs to be recognised. Mayors provide a clearly visible point of local leadership, with significant local agency and authority. They are a major point of democratic accountability. And they have an important role in the work described above on ‘Place Based Resilience’.

Every devolution settlement, and hence the powers and responsibilities of each Metro Mayor, is different. And the devolution proposals in the Levelling Up White Paper12 will add more variation. It is therefore unlikely that there is one solution to how best to recognise the role of Mayors in legislation. But it is important that that is done.

Regional Resilience Structures in England

Arrangements put in place after the abolition of regional resilience structures a decade ago are insufficient to capture the operational and efficiency benefits that could be achieved through cross-border collaboration between Resilience Partnerships, especially in the response to a national emergency such as the COVID-19 pandemic. It is clear that, over the past decade, regional collaboration has progressively eroded. Despite good support from individual Regional Resilience Advisers in DLUHC13, which English LRFs were keen to praise, the systemic support provided to regional collaboration by DLUHC is seen as weak.

There are effective regional collaboration arrangements in some parts of England (eg. the South West and North East), but not all. There are clear operational and efficiency benefits to putting regional collaboration arrangements onto a consistent, secure footing, underpinned by Regulations associated with the Act and supporting statutory guidance.

UK Government

The current distribution of stewardship responsibilities for resilience across UK Government departments is widely seen as weak and confusing – and operationally damaging in the response to a major emergency.

The majority of the VCS organisations we interviewed were clear that DCMS14, who have stewardship in the UK Government of the involvement of the VCS in building resilience, have not acted as an effective bridge between government and the VCS on resilience issues.

Several pointed out that DCMS officials were recruited and trained for a different set of attributes and skills. Most significantly, however, VCS organisations believed that having an intermediary layer between the Cabinet Office and VCS organisations would always impede operational clarity and effectiveness at the time it was most needed, in an emergency.

Opinion was divided on whether the role should sit in future with DLUHC or the Civil Contingencies Secretariat. But the compelling need for operational clarity in the response to an emergency meant that the majority of interviewees in the VCS and in Resilience Partnerships concluded that stewardship of the involvement of the VCS in building resilience should be moved from DCMS to the Civil Contingencies Secretariat.

Similar issues arose in respect of the stewardship role fulfilled by DLUHC of the work of LRFs in England. Effective local-national resilience arrangements need an ‘expert centre’ in the UK Government, with officials who have the knowledge, skills and experience to enable them to interface effectively with staff of LRFs; who have the convening power to join up Whitehall, bringing together and rationalising if necessary commissions from several UK Government departments rather than each sending its own request separately to LRFs; and who, where necessary, have the authority (and courage, built on competence and experience) to intervene with local bodies or Resilience Partnerships who are under-performing. This would include receiving and acting on issues escalated by LRF Chairs, as described above.

Some interviewees saw advantages in keeping the role within DLUHC given their local government stewardship responsibilities. But others pointed out that membership of Resilience Partnerships went well beyond local government, and that other policy priorities would always command greater attention within the department. And here, too, there was a strongly-held view that having an intermediary layer between the Cabinet Office and responders would always impede operational clarity and effectiveness in the response to a major emergency. We believe that stewardship of local resilience activity in England should be moved from DLUHC to the Civil Contingencies Secretariat.

The transfer of stewardship roles would go some way to reducing the perceived fuzziness of responsibility and leadership in the UK Government. But there is further to go. A wide range of interviewees, from across all sectors, contrasted the clear vision, visible leadership and drive provided in other areas of national safety and security, especially in cyber security and counter-terrorism, with the more opaque arrangements for the leadership of resilience- building work at UK Government level (although interviewees did comment favourably on arrangements in Scotland). Unfavourable contrasts were also drawn with arrangements in other leading countries, especially the United States, a wide range of EU members and countries in the Asia-Pacific region.

The Scrutiny Committee which considered the draft Civil Contingencies Bill recommended that the then Government gave careful consideration to the establishment of a Civil Contingencies Agency. The Government did not proceed with the recommendation. With the benefit of learning and hindsight, we believe that judgement to have been wrong. We believe that the time has come for the creation of a single government body which should provide a single, visible point of focus for resilience in the UK. Its leadership should be clear and credible, visible to those working on resilience in all sectors and to the public, both in normal circumstances and in the leadership of a national emergency. It should have a clear mandate, with the authority, drive and resources to build UK resilience across all areas of risk and emergency management.

The precise form of such a body would be for the Prime Minister, acting on the advice of the Cabinet Secretary. It need not follow the form of the National Cyber Security Centre, or of Emergency Management Agencies in other countries, although those have been praised by those we have interviewed. But its desirable attributes would be likely to mean that it was a self-standing body rather than a secretariat of the Cabinet Office, with staff drawn not only from the Civil Service but also from all sectors, who are knowledgeable, experienced and credible with their stakeholders. It will need the authority, credibility and convening power to join up work across government departments. It should have corporate governance mechanisms which design in the full and effective involvement of the Devolved Administrations and of representatives of all sectors, as well as providing for independent Non-Executives with substantial experience in risk and emergency management who can provide experience and challenge. Its culture will need to reflect the operational imperatives of risk and, especially, emergency management: agile, flexible, data driven, and delivery- and outcome-focused. And it should have a demonstrable passion for the pursuit of learning, improvement and excellence.

The new body should build two important cultural underpinnings to its work.

First, a demonstrable desire to reach out to gather and share wisdom and experience, going much wider than the UK Resilience Forum15. This is about more than creating ‘talking shops’: it will be important that the voice and contribution of front-line responders, VCS organisations, businesses and those affected by past emergencies is embedded in the development of policy and operational practice, so that they are grounded in reality and people’s needs. Counter Terrorism Policing has shown what can be done, in a highly- sensitive area, to reach out not only to statutory bodies but also to VCS organisations, businesses, academics and, most importantly, people who have been personally affected by terrorist incidents, to give them a voice and enable them to make a contribution in the solving of problems, and in the shaping of policy and operational practice. If this can be done for counter-terrorism, we are certain that it can be done for the much less sensitive field of UK resilience.

Second, the body, and especially its leaders, should seek to rebuild and sustain with stakeholders the spirit of partnership in a shared enterprise. We heard too many times for comfort that that spirit had been seriously damaged in recent years. We hope that it can be rebuilt.

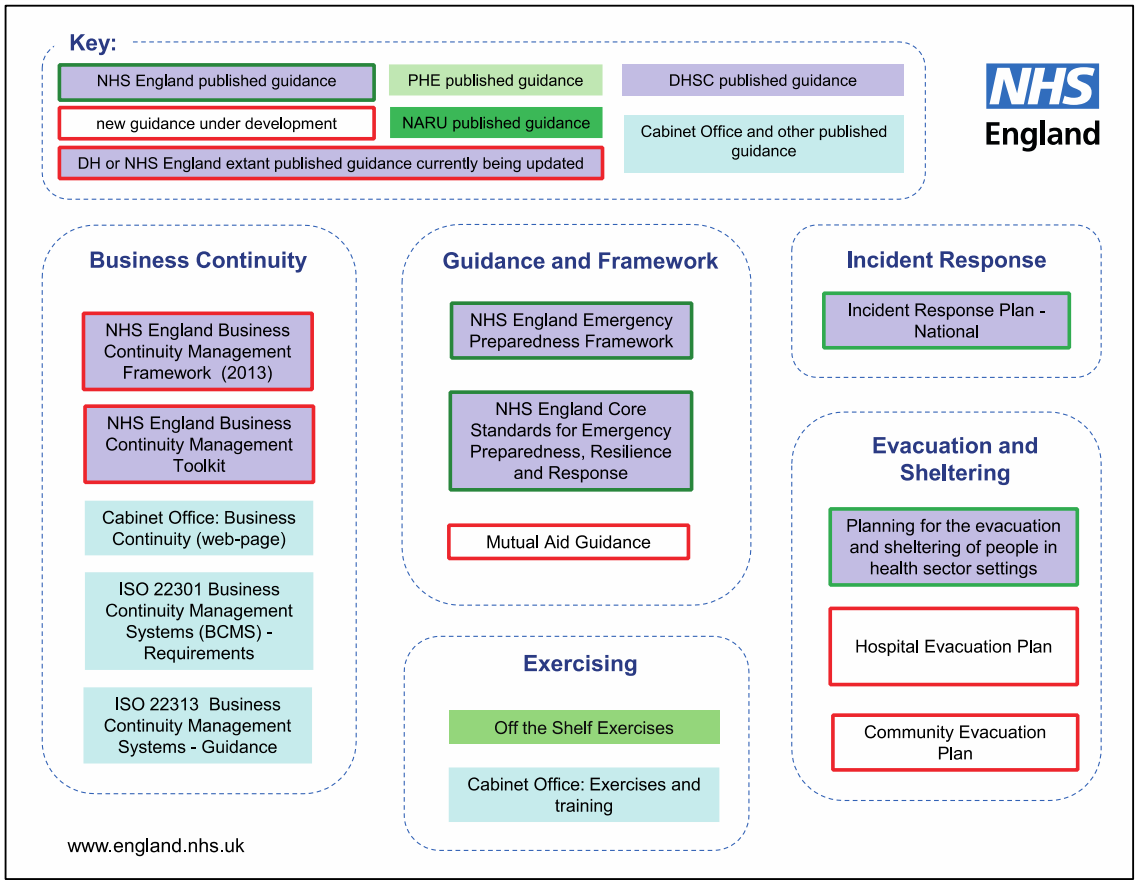

Doctrine and Guidance

Effective partnership working between organisations at national, regional and local levels rests heavily on a good understanding by everyone involved of what is to be achieved, and how that should best be done. Achieving a consistent approach and maximising the effectiveness and efficiency of the combined efforts of everyone involved is fundamental, especially, in the response to an emergency.

A major contributor to achieving this is having doctrine and guidance that is up-to-date, incorporates good practice, and that all organisations are aware of and can easily access and navigate. So it is gravely disappointing that so much of the key resilience doctrine and guidance has not been updated for a decade, especially the two major pieces of statutory and non-statutory guidance accompanying the Act: Emergency Preparedness16 and Emergency Response and Recovery17. Similarly, Responding to Emergencies: The UK Central Government Response. Concept of Operations18, a critical document which sets out UK arrangements for responding to and recovering from emergencies requiring co-ordinated central government action, has not been updated since April 2013.

Single- and multi-agency doctrine and guidance which act as the spine of coherent resilience-building activity across the resilience community need urgent – and then regular future – updating to ensure that they reflect developments in policy and operational practice and learning.

The volume of statutory and non-statutory guidance available to local bodies and Resilience Partnerships has grown significantly in the last decade. The absence of a central directory of all the guidance now published by the UK Government and other key bodies means that planners struggle to keep track. The UK Government should develop and publish digitally for use by local bodies, Resilience Partnerships and government departments, a simple map of current doctrine and guidance.

Legal and other developments over the last decade may mean that some areas of non- statutory guidance should now be made statutory. It is clearly important that the way in which services are delivered to meet people’s needs are compliant with current law and meet professional standards in the way in which they are delivered. Our judgement is that there is a strong case for substantial changes to the legal status of some doctrine and guidance. One example is whether the emergency co-ordination structures set out in current non-statutory guidance19 should be made statutory. The UK Government should examine whether legal and other developments, including the recommendations of public Inquiries, mean that some areas of non-statutory guidance, especially on safeguarding, humanitarian assistance and emergency co-ordination structures, should now be made statutory.

Terminology – including that which covers important principles and operational practices – varies across the wide range of single- and multi-agency doctrine and guidance. Since 2007, the Civil Contingencies Secretariat has helpfully led on production of a Lexicon of Civil Protection Terminology20. But this has not been updated since 2013, is not being used consistently and has become unmanageable and not user-friendly. We recommend that the Lexicon should be refreshed, made a more accessible, user-friendly, reference document, and then used consistently to inform the writing of all single- and multi-agency doctrine and guidance.

Excellence

We note above that resilience capability and capacity has degraded over the past decade, projects have been started but have not progressed, and good practice in other national security sectors has not been imported. Quality has suffered.

Skills and Training

Although there is good practice in some sectors, especially the police and fire and rescue services and the NHS, it is clear from our research and interviews that current arrangements for the definition of the competences21 required of individuals and teams engaged in resilience-building activities are inconsistent and fall well short of what is needed.

That is not a position that can continue. In our view, it is the development of human capabilities which will make the greatest contribution to improving UK resilience. We have therefore identified the need for development of a Competence Strategy and associated Resilience Competence Framework for use by everyone with a substantial role in building UK resilience.

The Framework would need to cover both individual and team competences and could sensibly build on the previously-issued but rarely used National Occupational Standards, although these would need substantial updating and alignment with competence standards already in place in other sectors and regulatory regimes, and to be made more useable in front-line organisations. Once developed, the Framework should be subject to regular review.

We believe that the task of developing and promoting the Competence Strategy and Framework would, in the short term, fall to the Cabinet Office, working with stakeholders from all sectors, professional bodies, employers and the higher and further education sectors. However, we also recommend that the UK Government should pursue with existing professional bodies whether they would, collectively, wish over time and with Government support to create a governance and regulatory body for UK resilience.

Implementation of the Competence Strategy and Framework will need the provision of sufficient, high-quality, accredited training to enable individuals and teams to undertake the necessary professional development, along with arrangements for them to demonstrate and validate their competences on a regular basis. There is a culture of well- structured training and continuous professional development in the emergency services and in the health sector. But this is not seen in all designated local bodies. And often this training is, for understandable reasons, focused on the needs of a particular sector, with limited focus on multi-agency working.

The resilience training that is carried out is now mostly undertaken in Resilience Partnerships. That has many strengths. Training can be locally contextualised. It enables the provision of training to participants whose commitments would otherwise make it difficult for them to attend training courses at remote establishments. It means that training can be delivered to entire teams. It enables the provision of training to those (eg. in VCS organisations) who would otherwise struggle to arrange or afford their own training. And it is more cost-effective. It is clear that Partnerships are all striving to offer good training on these lines, despite having very limited resources. But they are caught between two areas of UK Government neglect. Despite their best efforts, they cannot on their own and at current levels of resourcing equip everyone with a significant resilience role with the competences they need. But the Government has failed properly to recognise and support the shift to in- house resilience training. The result is a training system that falls a long way short of what is needed, including in the content, quality and format of training offered by the Emergency Planning College which is clearly not addressing the needs of front-line organisations. Each Partnership is developing its own training programmes and materials, with risks of inconsistency as well as the obvious inefficiencies. And there are no arrangements for checking that the training provided is compliant with legislation and doctrine and is up-to- date.

We believe that there is a compelling need for a fundamental ‘reboot’ of the current resilience training ecosystem, including a fundamental reboot of the Emergency Planning College. That should be led by the UK Government and be set against the goal of providing the necessary training and development opportunities to allow everyone with a significant resilience role to develop the competences and confidence they need. It should build on good practice seen in other national security fields, including the use of modular courses and digital delivery, and the provision of training to organisations outside the public sector. It should have a heavy emphasis on training being provided in local areas to make it easier for individuals and teams to undertake training and development. That will need to be supported by the provision to Resilience Partnerships of centrally-produced and maintained – and accredited – core training materials which they can adapt and use. And it should be underpinned by a national register of recognised trainers and subject matter experts which Resilience Partnerships can call on.

Similarly, there are weaknesses in the provision of training to those with senior leadership roles, covering not only the work they do as individuals but also when working together as a team in the multi-agency leadership of the response to a major emergency. Not all Resilience Partnerships have the resources and capacity to undertake the training they would wish of their command teams. There is no requirement in some sectors for those likely to fill senior leadership positions in the management of an emergency to undertake the necessary training. And there are no arrangements to assure the collective competence of the command teams whose decisions will have direct consequences for the safety and wellbeing of the people affected by a major emergency.

The public will rightly expect the team managing the response to emergencies to be individually and collectively competent in fulfilling its role. In our view, the National Police Chiefs’ Council has set the benchmark, under which all police forces must have the capability and capacity to deploy trained and approved strategic commanders for civil emergencies.

We recommend that the same standard be applied to all other sectors, so that senior leaders from Category 1 responder bodies who are expected to be core members of Strategic Co-ordinating Groups in the response to a major emergency should be required to attend a strategic emergency management training course every three years, and subsequently undertake annual CPD22, in order to be assessed as ‘approved’ to fulfil that role. This obligation should be mandated in an amended Act or future legislation and supporting statutory guidance.

We recognise that this will generate a significant increase in the training requirement. We applaud what has been done by the College of Policing to adapt their command team training courses and boost capacity to meet the needs of Resilience Partnerships. In the belief that they (and we hope other accredited training providers so that the provision of training does not rest on a monopoly) will generate sufficient capacity, we recommend that the new training obligation should be phased in over a three-year period. In recognition of the mutuality of the benefit gained, the UK Government should provide specific, time- limited co-funding of the costs.

In other public safety fields, command teams are subject to external assessment and validation regimes. We believe that to be a discipline which should have equal applicability for those managing the response to major emergencies which could cause at least as much, if not more, disruption and harm. We therefore tested with interviewees across a wide range of local bodies whether command teams should be formally ‘accredited’ for their demonstrated competence in the management of the response to major emergencies.

We share the view of the majority of interviewees that there is a need for arrangements by which the collective competence of command teams is demonstrated and assessed. But we suggest that the journey to formal accreditation should be taken as a number of steps. In the near term, the weight of evidence, and what we believe to be reasonable public expectations, point to the introduction of arrangements which stop short of formal accreditation but which do provide for the external assessment of the collective performance of command teams. We therefore recommend that an amended Act or future legislation and supporting statutory guidance should mandate that core members of Strategic Co-ordinating Groups should undertake at least one command team exercise per year, externally observed and assessed by independent external assessors against the requirements set out in the Resilience Competence Framework. If collective performance is assessed as being seriously weak in any areas, Resilience Partnerships should be required to put in place an improvement plan and to evidence improvement in the areas that fell short of the expected standard within a given timeframe.

There is an obvious need for civil servants in government departments performing resilience roles to have the knowledge, skills, attitudes and experience – including in emergency management – to perform their roles and to enable them to interface effectively with Resilience Partnerships. The need is given urgency by the substantial evidence we received of serious weaknesses in the competence of staff of UK Government departments engaged in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, especially their lack of basic understanding of resilience structures and the basic principles of emergency management.

These weaknesses have been identified and are being addressed as part of the work of the Government Skills and Curriculum Unit in the Cabinet Office. However, as with local bodies, it cannot be left to ‘best efforts’ and chance that at least the core members of departments’ emergency management groups, and those who are expected to participate in cross- government emergency management groups, are individually and collectively competent to fulfil their leadership role in the management of major emergencies. The same disciplines of building and demonstrating individual and collective competence should apply as much to civil servants in UK Government departments as they do to staff of local bodies.

We therefore recommend that the Resilience Competence Framework described above should set out the competences required of civil servants with resilience roles. Training to allow individuals to achieve those competences should be incorporated into the training provision of the Government Skills and Curriculum Unit and, potentially, the new Leadership College for Government.

As with local bodies, departments must have the capability and capacity to deploy trained and approved civil servants for emergencies requiring a single department or cross- government response. So we recommend that senior leaders of departments who are expected to be core members of their emergency management groups should be required to attend a strategic emergency management training course every three years, and subsequently undertake annual CPD, in order to be assessed as ‘approved’ to fulfil that role. This obligation should be mandated in an amended Act or future legislation and supporting statutory guidance.

These should also mandate that core members of departmental and cross-government emergency management groups should undertake at least one command team exercise per year, externally observed and assessed by independent external assessors against the requirements set out in the Resilience Competence Framework. Again, if collective performance is assessed as being seriously weak in any areas, an improvement plan should be put in place with improvement evidenced in the areas that fell short of the expected standard within a given timeframe.

We were particularly mindful of the critical role played by Government Ministers and Special Advisers in the response to emergencies. It is vital that they too have a basic understanding of resilience structures at national level and the role and status of Strategic Co-ordinating Groups at local level, along with the basic principles of emergency management. We therefore recommend that the UK Government should consider how best to support Ministers in the development of the emergency management competences they need to lead a single department or cross-government response to a major emergency. Identified Ministers should also ideally undertake at least one cross-government command team exercise per year.

Links with Academic Institutions

Higher education institutions (HEIs) have an important role to play, in the education of people who work, or wish to work, in the resilience field, and in the contribution they can make from their research to the development of policy and operational practice. We therefore interviewed a number of HEIs on the courses they taught, the research they conducted, and especially the level of their engagement with the UK Government and Resilience Partnerships, to establish whether there was an effective two-way flow of information and learning.

HEIs consistently identified two areas of concern. First, the lack of a national Resilience Competence Framework for use in the development of courses and materials was seen as a barrier to ensuring that students were equipped with the right skills and knowledge to meet the needs of their future employers. Clearly, the Resilience Competence Framework, once produced, should be made available to HEIs to inform their course design and teaching.

The second and more significant gap was the absence of any meaningful engagement by the UK Government with HEIs. As a result, HEIs were not always sure, and felt unable readily to check, that their materials were up-to-date with government policy thinking or operational good practice. And the UK Government is clearly not exploiting the contribution which HEIs can make through their research to the development of policy and operational practice.

We recommend that the Civil Contingencies Secretariat should establish and promote a formal engagement mechanism with HEIs seeking advice on current resilience policy and operational practice, or who wish to pursue or promote research of benefit to UK resilience.

In contrast, the evidence from our interviews suggested that contacts between HEIs and Resilience Partnerships are stronger. There has been an observable recent development in linkages between Partnerships and HEIs in the same local area. But there was a general acceptance that there was scope for doing more, especially in areas where HEIs can offer analytical expertise in the development of risk assessments and emergency plans to more fully reflect local demographic, socio-economic and other data and information which they hold.

HEI research leads also noted that there was no single government department collating data on research topics which the UK Government and local bodies wished to see pursued, and then working with research funding bodies to commission this research. We recommend that the Civil Contingencies Secretariat should collate from across central government departments and Resilience Partnerships a list of those UK resilience issues which would benefit from further research and pursue this with HEIs and research funding bodies.

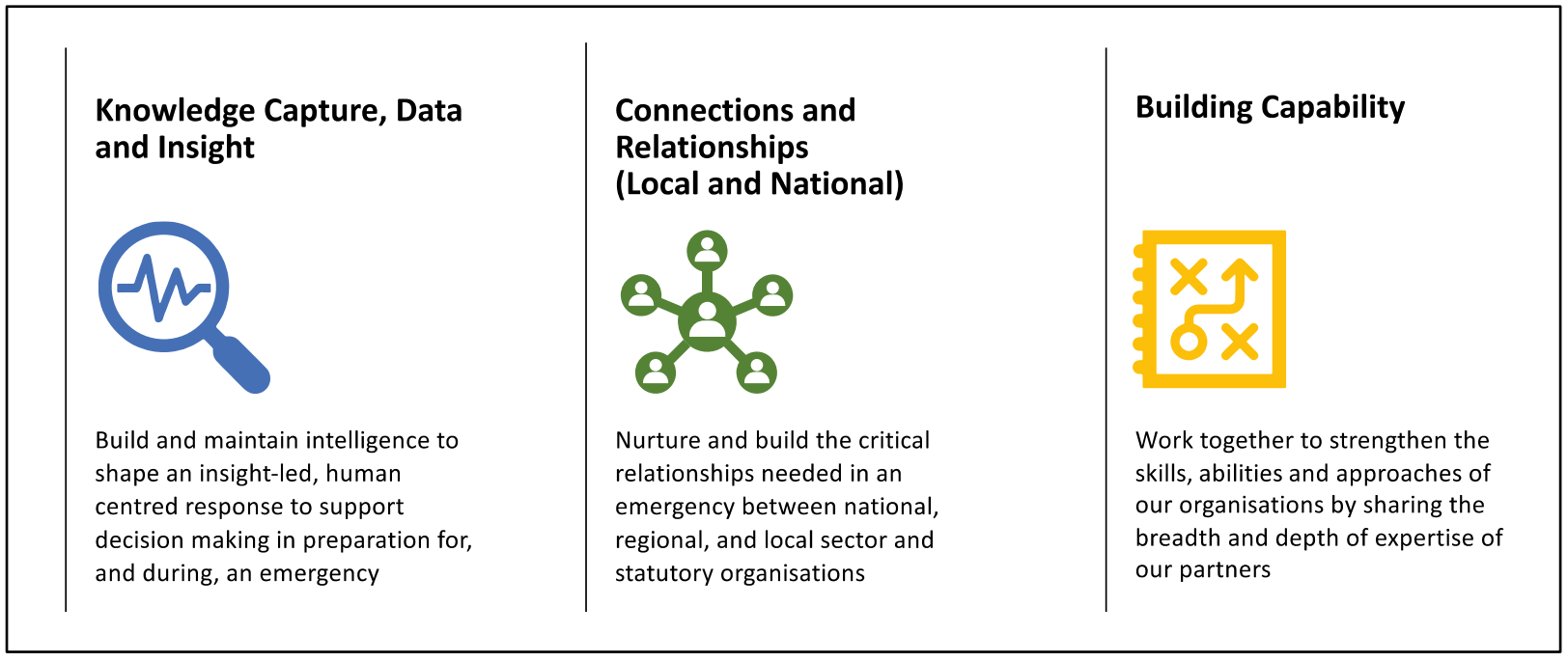

A Centre of Resilience Excellence

One clear overarching conclusion, drawn out in interviews across all sectors, is that, in the resilience field, the UK Government has focused heavily over the past decade on processes and products at the expense of people. It has not sufficiently invested in the knowledge base, occupational competence instruments, quality mechanisms and – above all – the visible signalling which encourages the pursuit of excellence in UK resilience. We have therefore tested in interviews the value of adopting in the resilience field the mechanism classically used in other fields, including other areas of national security, which wish to pursue and embed professionalism and quality – the creation of a Centre of Excellence.

We believe there is a pressing need to create a Centre of Resilience Excellence (CORE). We found widespread support for this concept. Its functions could include: leading the development of the Resilience Competence Framework and the fundamental transformation of the resilience training ecosystem we recommend above; providing specific training courses and command team exercising; more broadly, overseeing the availability of training courses and command team training and exercising across all providers in the UK; developing and making available to Resilience Partnerships a national register of recognised trainers, subject matter experts and providers of multi-agency emergency management training; facilitating mentoring, coaching and secondment opportunities; acting as a point of engagement for HEIs, including making connections between HEIs and Resilience

Partnerships; collating and promoting ‘Areas of Research Interest’ and analysing, synthesising and disseminating the findings of relevant UK and international research and lessons identified reports; creating and maintaining doctrine and guidance and a Knowledge Hub of reference materials; and providing thought leadership on resilience in the UK.

It would be wrong for the CORE to operate within its own silo. It needs to work with HEIs and a wide range of government training institutions, including not only the Emergency Planning College, College of Policing and the Fire Service College but also, for example, the Defence Academy and the Diplomatic Academy. There is clear value in drawing on academic teaching and research disciplines, as well as cross-fertilisation of training between different institutions and cultures, especially between the ‘civilian’ and ‘military’ fields, and between ‘home’ and ‘overseas’ experience and practice.

That means that it is unlikely that a Centre of Resilience Excellence could become self- financing. But, whilst it would need a small physical ‘head office’, we believe that, as well as its digital presence, its ability to draw on geographically-distributed hubs – both government sites and possibly those of HEIs – would sharply reduce costs whilst radically increasing engagement.

Creation of a Centre of Resilience Excellence would provide the visible signalling which encourages the pursuit of excellence in delivering the resilience agenda. In that vein, we believe that the creation of the CORE as part of the newly-created UK College for National Security23 would be highly beneficial, provided that it was genuinely open to and able to meet the needs of all sectors – public, private, voluntary and community – and not just the UK Government as the current proposal implies. It should also be able to build strong linkages to, and possibly joint ventures with, HEIs not only on teaching but also, and especially, on research and learning.

Building a Learning and Continuous Improvement Culture

We heard from a wide range of interviewees that there is limited evidence at a national or local level of a learning and continuous improvement culture. This was sometimes portrayed as being due to a lack of time and resources. But, more worryingly, it was also attributed to a fundamental lack of desire to disturb the status quo, or to a perception that there was nothing to learn from others, including from international experience.

Interviewees particularly expressed their frustration that, despite the creation of Joint Organisational Learning (JOL) Online, which aims to collate and highlight lessons from exercises and emergencies, there is still not a systematic process to make sure that debriefs consistently take place following exercises and emergencies, that lessons identified are shared widely, and that they are then adopted and embedded in all relevant organisations and operational practices.

The development of a culture of continuous, systematic learning and improvement is well- trodden ground in other fields, with substantial experience which can be drawn into UK resilience. We recommend that, as the first two steps in turning perceptions around, the Cabinet Office should signal the need for, and encouragement of, a learning and continuous improvement culture; and demonstrate that commitment by putting in place systematic arrangements for its promotion and pursuit, led by the Centre of Resilience Excellence.

Validation and Assurance

The need for effective validation and assurance arrangements in an area of such significance for people’s safety and wellbeing has been widely accepted over the past 20 years. There is established practice in some risk areas, and in some sectors. But those arrangements do not cover all local bodies, all risks, or Resilience Partnerships as a whole.

Our interviews with front-line organisations and Resilience Partnerships brought out clearly that they would welcome arrangements through which it was possible to assess their performance and identify areas for improvement. And there was widespread agreement on the need for the results of all those assessments to be brought together by the UK Government into an overall assessment of the quality of resilience in the UK, areas of best practice on which Resilience Partnerships could draw, areas for system-wide improvement – and, especially, of how ready the UK is to tackle risks and respond effectively to emergencies.

Current validation and assurance arrangements are wholly inadequate against those goals. Performance standards have progressively developed over the period since 2010 but, critically, have no teeth. There are no current systematic, routine arrangements to monitor the performance of all bodies with legal duties, and of the way in which those bodies act in partnership. As far as we have been able to establish, at no stage has the UK Government used its powers in law to take formal intervention action with a designated local body or with a Resilience Partnership overall on performance grounds. And there are no systematic arrangements in place to generate an assessment in the centre of government of the overall quality of resilience in the UK, for use by UK Government Ministers and the UK Parliament.

We recommend improvements in two areas: to Resilience Standards, so that they are crystal clear about ‘what good looks like’; and more significantly on performance monitoring arrangements.

Resilience Standards

The National Resilience Standards published in 2020 have been widely welcomed. It is clear that they are being used in self-assessment by Resilience Partnerships and local bodies. They provide a sound basis for assessing performance. But they could usefully be crisper. And they need to be precise on the legal force of each of the three sub-sets of performance measures (“must/should/could”) against each Standard. Once revised, they should be adopted consistently by HMICFRS24 and CQC25 in their inspection regimes.

The fundamental gap which needs to be addressed is that, in the same way as UK Government departments do not have resilience duties in law, so there are effectively no standards governing their performance. This weakness matters and needs to be addressed, especially given the widespread criticisms we received about their competence in the management of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We recommend above that departments should be subject to the same set of legal duties as local bodies. We can see no valid reason why the performance of UK Government departments against their duties should not similarly be assessed against defined standards, which capture their vital leadership role in many areas of risk and emergency management. We recommend that the UK Government should develop and publish additional Resilience Standards covering the performance of UK Government departments.

The Act has provision for both the monitoring of performance and enforcement. But they are limited in their scope: statutory guidance supporting the Act makes clear the expectation that the powers would be narrowly and infrequently used. Unsurprisingly, as far as we have been able to establish, they have never been used.

Although useful, self-assessment by local bodies, Resilience Partnerships and UK Government departments against the Resilience Standards is simply not sufficient. As many front-line organisations have pointed out to us, there is a risk of organisations ‘marking their own homework’. And the single-agency inspection regimes managed by HMICFRS and CQC, although valuable, do not provide an assessment of the performance of all designated bodies acting in partnership. Ultimately, a genuinely rigorous performance monitoring regime requires external, independent review, drawing on people with expertise and experience, looking across the activities of the entire Resilience Partnership or government department, against well-defined standards.

We therefore recommend that multi-agency validation should be undertaken by a new team hosted by the Civil Contingencies Secretariat, staffed by experienced, knowledgeable practitioners who will carry credibility with those with whom they deal. The team need not be large. The focus of validation reviews should be on learning and improvement, with reviews conducted in a spirit of collaboration with the Resilience Partnership or department so that recommendations are more readily accepted and acted upon. Reviews would thus ideally be conducted at the request of and in support of the Chair of the Partnership or head of the government department concerned, with each Partnership or department being the subject of validation at least every three years. The local government Sector-Led Improvement model most closely mirrors the improvement regime we recommend.