Back in September 2022, NPC published a paper by Professor John Beckford on “A Systemic Perspective on National Preparedness”, which identified a set of themes to be explored in a series of follow-up papers. We start 2023 by sharing the first of those follow-up papers. Here, Professor John Beckford and Richard Berry (Loughborough University) explore the role of data in national preparedness, focussing on how we can come to know, understand, and respond to what matters.

Introduction

The National Preparedness Commission published a paper on “A Systemic Perspective on National Preparedness” by Professor John Beckford on 1st September 2022. The paper concluded with a set of emerging themes on national preparedness to be explored in more depth through a series of follow-up papers. The five themes included: the role of data, systems failure, discriminating levels of urgency, organisational resilience, and trust and mutuality.

This paper by John Beckford and Richard Berry, Loughborough University, is the first of those follow-up papers, and it explores the role of data in national preparedness. In summary, the paper responds to the following provocation: ”How can we come to know, understand, and respond to what matters?”

Expanding this further, the paper explores:

- In an increasingly digitally-enabled world, how can we capitalise on and exploit data to support preparedness, without becoming overwhelmed by the scale of ‘big data’?

- What is the role of data in preparedness, and what mechanisms can we use to convert data to information, insight, knowledge, and wisdom?

This paper draws from a bricolage of theory and practice. There is no playbook, and nor should there be; preparing for a repeat of the last ‘event’ resembles mechanical hindsight rather than thoughtful foresight. This paper outlines key issues of data collection, aggregation and interpretation and the architecture for decisions, showing how that may reveal potential tipping points or ‘black swan’ events (Taleb 2007). It concludes with implications for local, regional, and national leadership. Our key assertion is that national preparedness is a complex system that needs to be managed dynamically, and that to do so requires a systemic mindset; an holistic alternative to the bureaucratic and functional command-and-control structure, which is so pervasive today, and which is no longer wholly fit for purpose.

National Preparedness: A Wicked Problem

The task for a nation seeking preparedness is two-fold. First, it must prepare its various enabling functions to mitigate known risks. Second it must develop the capability to deal with risks that are, yet, unknown. This requires the development of a higher order problem-solving capability that can both extrapolate current evolving circumstances and develop future risk scenarios.

Mitigation of known risks and, most particularly, preparing to mitigate as yet unknown risks are best characterised as ‘wicked’ problems. A wicked problem (Beckford 2021) is one which is difficult to solve because of the dynamic, complex, and perhaps contradictory nature of the question being considered. Comprehending national preparedness, along with the question of ‘what data do I need to gather?’, fits the definition of a wicked problem.

For a nation to be prepared, it needs first to be risk aware. This means being cognisant of its capabilities and weaknesses, as well as the opportunities and threats in its environment; and being able to both capitalise on opportunities and mitigate risks effectively and timeously. Risks exist across all the fundamental and social infrastructure elements that enable society to develop and operate – including private, state and third sector elements. Someone with a basic grasp of systems dynamics will readily see that there are systemic interactions between individual elements of this infrastructure – they have a continual effect on one another.

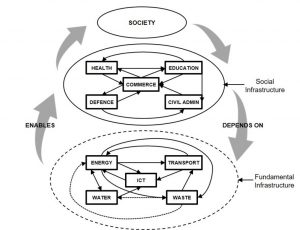

There is also a systemic emergence from them (see Figure 1), i.e., the operations, interactions, and dependencies between the elements combine to create and control the social infrastructure from which ‘society’ emerges. In this sense society is a real and observable product manifesting from the interactions of the identified elements and their context, i.e., the international relationships, social, economic, and political and climate environment in which the nation exists. Clearly then, a nation needs to understand and manage the elements of its infrastructure, and their interactions and interdependencies, to ensure national preparedness in the prevailing context at any time.

Figure 1: An Infrastructure System of Systems (Beckford 2021)

Applying a systems lens to the ‘wicked problem’ of national preparedness, leaders can develop a viewpoint from which they can more adequately comprehend what is happening around them. They require information to first build this comprehension and then to use it to create a ‘bubble of safety’ – a national capacity to anticipate, pre-empt or prevent threats; and where that fails, to restore society after a threat event. With a dual focus on how our society is functioning now (or in the absence of shocks) and on how we can address future turbulence, we must develop a system for decision – the means and methods for studying activity patterns and anomalies (non-patterned behaviour) in society, economy, commerce, industry, and relationships. The key to all of that lies in how we capture, structure, interrogate, extrapolate, and interpolate data.

Challenges in Gathering Data

Data forms the building blocks of information. It is the architecture and aggregation of data into information which provides propositions for decision-making. Knowledge and wisdom are built through the application of information. This simple assertion belies a process which is rarely straightforward. Data and the processes associated with it may well be neutral, but the processes and structures we accumulate and manage it through are not. They are created and shaped by all of us, and we bring to them all of our lived experiences, insights, biases, preferences, and prejudices. This provides complexity enough, but there is an added complication in that not all of the sources of data required for a preparedness dataset are public goods. Much of the data is held by corporations or public bodies and may be subject to rules of confidentiality or have commercial costs and value. Hence, we need to answer three questions – not just ‘What data do we need? but also:

- What mechanisms must be applied (digitally) to structure, manage and maintain it?

- What organisational arrangements will be needed for its capture, interpretation, curation, and governance, and for the protection of individual interests?

Distributed Data

Data relating to national preparedness is – at least in part – derived from national infrastructure artefacts and their controlling systems. Other datasets come from public services. Infrastructure artefacts are always exceptionally large, some are highly distributed (both geographically and organisationally) and many are old (pre-dating any form of digital data capture) – all of which makes it difficult to know their condition, status, veracity, and value. Equally, some public services are highly distributed, geographically, and organisationally. They may be operated through statutory bodies or trusts, each holding ‘their’ data about services, performance, clients, and customers. They keep that data to themselves and managing it in their organisational interest, as laid down in law. The data is perhaps unknowable by anyone outside the organisation, and certainly in some cases unobtainable or protected. There is a substantial challenge to national preparedness in untangling this situation – in understanding what data exists, how it is (and can be) used, and how to access and employ that data in preparedness decision-making in the necessary timeframes, ethically and legally.

By contrast, some data is in the public domain, and is routinely captured, verified, and published. Such datasets can offer an opportunity to those concerned with national preparedness – at least from a demographic perspective. Population data such as births and deaths, as well as healthcare, education, and judicial data, are continually recorded. From these sources we can make useful assertions about population growth, decline, age, sickness, capacity for work, capability for learning and research and many other assertions about the needs of the population. We can, for example, estimate and prepare for local and national demand for hospital beds, education services, transport, and communications and infrastructure. Tax data, derived from the regular tax returns of citizens, corporates, importers, and exporters provides useful, though not necessarily precise, information about private and corporate economic activity as well as the national and international business activity that underpins it.

Overall, it is relatively straightforward to gather a good enough understanding of the national ‘self’. It is much harder to gather useful comparative data on other nations or contextual information on the global physical environment (planetary ‘health’), to which the nation needs to be able to pre-empt or respond. Such data includes political developments and emergent criminality, including both terrorist and organised crime activity, and extends to less explicitly or obviously risky matters such as international supply chains. These supply chains can be suddenly and significantly disrupted by accidents and weather events as well as economic factors, state actions and sanctions. We have seen, for example, the recent disruption of gas supply to European countries. However, the UK implications of events is not always so readily apparent. For example, the tsunami off the coast of Japan in 2011, which damaged the Fukushima nuclear power plant and caused floods in Thailand, also disrupted manufacturing activity in the UK.

Structuring Data

Once relevant datasets are identified, systems of data capture need to be established. Often this involves data already held by existing functional departments of the state. To inform and contribute to national preparedness, that data needs to be aggregated, abstracted, depersonalised, and disseminated to areas such as policing, healthcare, and education. As well as enabling demand and forecasting information, the same data can be brought together in coherent and systemic models capable of simulating threats and opportunities, and the possible required responses. The challenge lies in structuring such models so that they embrace all of the functionally acquired data, making risks and opportunities in each functional domain visible in and through each of the others. This creates the possibility that, for example, an emergent healthcare risk can be managed not just through healthcare delivery but also through education; an emerging crime threat might be addressed not just through the lens of technology but also through education. Such approaches to data structure and sharing are novel and challenge the established functional, siloed domains, budget envelopes and associated ‘territorial’ behaviours. However, it is only through such holistic approaches that systemic opportunities maybe capitalised upon and systemic risks neutralised.

Governing Data

The concept of aggregation and data sharing raises the thorny challenge of ‘quis custodiet ipsos custodes’ (who will guard the guards themselves?) There are clearly risks involved with placing all our data into the hands of the state. To be prepared we need to develop a systemic, coherent picture of our world, but we need also to take action to prevent its abuse by those who would serve their individual purposes, rather than those of society as a whole. It may be that the only route to guarantee this is to maintain the current state of functionally-biased ignorance and incoherence, an approach likely to amplify the established disorder. An alternative is to consciously create moral, ethical, legal, and cultural frameworks that act to inhibit the worst excesses of any self-serving impulses of those elected to political power and constrain the ability of public servants to act ultra vires. This can be partially achieved by adopting distributed data architectures and governance structures, such that no individual, or group of individuals – even acting in concert – can control them all. A second and most significant element of such control is the active engagement and participation of the eligible population in the processes supporting demos.

Democracy and the related concept of participation along with subsidiarity are essential levers in preparedness structures. The principle of subsidiarity requires us to hold data as close as possible to the individual citizen which complements notions of individual responsibility alongside democratic engagement. This reinforces the distributed nature of things, and by building distributed decision support systems for resilience and preparedness, we can to some extent preserve the autonomy of the individual. Effective control of personal data protects the sovereignty of citizens and simultaneously embeds subsidiarity in the data structure itself. This notion holds that social and political issues should be dealt with at the most immediate level of management that is consistent with their resolution, defined as competences.

Clearly then, it is undesirable, if not impossible, to seek to hold all the necessary data in one place. Rather, the aim is to hold and manage data that supports national preparedness in distributed structures with decisions allotted to citizens themselves and thereafter to recognised bodies at the most relevant level in the structure. A practical solution would be to capitalise on structures of local and national government that already exist and that could be repurposed.

A Need for Leadership

How do those with leadership responsibilities prepare to be effective in this radically different, data-rich, systemically informed context? The term ‘leadership’ in this context refers to those individuals’ (politicians, public servants, and company officers) taking responsibility for developing and leading their organisations or communities, and those preparing (with the help of data) for all possible futures. This latter point is contentious; many leaders do not see future planning as part of their role, preferring to delegate this to a functional specialist as a matter of compliance.

Effective leadership for preparedness is not determined by the set of managerial or bureaucratic skills routinely taught in leadership courses. One simple but revealing indicator of preparedness would be whether organisations have a comprehensive, persistent, and evolving data strategy. This could be expected to include basic elements such as a focus upon regulatory compliance, information security measures, as well as an exploration of how Artificial Intelligence (AI) and analytics can support the organisation. Public services in particular continue to be less than perfect in this regard, as shown by attacks such as ‘WannaCry’ on the NHS in 2017; an attack that demonstrated the global rather than national nature of this threat type. More insightful leadership is required.

It is worth reflecting on why our leaders have such a focus on the present, at the expense of the future. One contributing factor is the evolution of reductionist performance targets applied to UK public organisations, which are then used as models for ‘best practice’ elsewhere. If leaders’ jobs and status are retained or lost on the basis of current performance data (often economically-focussed), then they will have little incentive to prioritise upon what tomorrow may bring. The adage ‘what gets measured gets managed’ is certainly hard at work here. There may also be a constitutional tension in public services between prioritising what is important for the organisations in question, and the congenital metrics required by statutory regulators or political promises. Notwithstanding this, we assert that the moral case for preparedness leadership is based upon a duty to protect, anticipate, and develop capabilities.

Leading Through Data: Anticipatory Reasoning

So, what do we mean by ‘anticipatory reasoning’? A functional definition is based upon the ability to use data which has been accessed, acquired, processed, and considered in order to create knowledge about systemic influences and threats. Responses can then be explored and tested. This anticipation contributes to reasoned inferences about preparedness, namely the systemic interventions which may be required to respond to particular system states. Capabilities at recursive levels can then be developed, adjusted, or discontinued. Anticipatory reasoning is therefore based upon the idea of systemic cycles, the speed and nature of which may not be within our control. This approach requires an alteration in leadership skills and insight.

The notion of digital transformation has been with us for over a decade, but progress towards it may be regarded as patchy. Conceptually, it appears tired and potentially redundant. We might wish to consider a more relevant approach to change and leadership for data organisations. We are moving inexorably towards a patchwork of 4GLTE and 5G data speeds, distributed and quantum-influenced data environments. Emerging technologies and infrastructure, such as distributed green energy, need a qualitatively different approach than simple digitisation of existing processes.

The requirement is for ‘effective data capabilities, within a clear and well-led approach, for national preparedness’. Easy words, but it has proven to be a challenging prospect. The expensive and controversial ‘withering’ value of Covid-19 apps during the pandemic offers one example of a situation that could have been better supported by more effective anticipatory reasoning. Regardless of virus type, the requirement for data-led contagion management could have been foreseen a priori, resulting in a foundation of preparedness that could have been built in an agile and targeted way (White and van Basshuysen 2021).

As a case study, the Covid-19 app suggests that preparedness requires leadership of change, built upon an effective understanding of cybernetics; communication and control within the population and machines (Wiener 1961). The requisite understanding can only be developed through the effective aggregation of data into a source of usable information. As leadership of data capabilities is a balance between managing today and changing for tomorrow, herein lies a central challenge. How many organisations can demonstrate a strong and effective commitment to reasoned anticipatory knowledge creation? How might they then use reasoning to become adaptive and dynamic systems in terms of preparedness? It is unclear if current leadership education, regardless of sector, supports future leaders in this respect.

A complication in the paradox between leading today and leading for tomorrow is highlighted by both Beer (1992) and Beckford (2021). They emphasise that institutions are inclined to perpetuate themselves by doing ‘more of the same’ rather than to adapt or evolve, yet it is these bureaucracies which need to develop their capability to capture and utilise data to meet the challenges of national preparedness. The strategic future is characterised by systems experiencing the effects of variety. Our systems of preparedness require us to think differently.

Leaders in national preparedness need to make use of anticipatory reasoning, but to do so in full recognition that such practice is inherently uncertain – it is akin to playing an infinite game (Carse 2012 and Sinek 2019). Games in this context are not to be confused with frivolous and trivial activity, but rather as recognised methods of strategic learning for individuals, groups, and organisations. Self-learning systems are essential for resilience and underpin the need for constant iteration. These both need effective data strategies to enable effective use of anticipatory reasoning.

Leadership should recognise that their purpose is not to win; this is not about a ‘zero sum’ game of winners and losers. For this reason, politically slanted lexicon is often unhelpful. For example, metaphors resembling ‘battle against’, describing performance as ‘success’, ‘failure’, ‘defeat’ and victory’, all portray a finite game of win or lose. Preparedness is not a spectator sport for silverware, nor is it a vehicle for mythical ideas of ‘zero tolerance’. Resilience is about recognising the recondite and obvious needs for systemic tolerance to risks and threats which cannot be eradicated. Tolerance arguably exists within a mix of social, economic, political, technological, environmental, legal and cultural conditions. We need to play the right game.

Organisational leaders at all recursive layers should seek to keep up, to survive and ideally to thrive. Some environmental perturbations can ultimately kill or wound us, but conversely, they may also run out of drive, impact, or resources. At some stage, a new normal based upon a state of systemic equilibrium may be established and the game continues. The leadership task is to apply knowledge and wisdom to simultaneously navigate the turbulence and be prepared for the ‘new normal.’

There are pitfalls within a set of apparent ‘truths’ that help to define this asymmetric existence (Berry 2022). Rules can change with no warning as the game emerges. Equality of chance between players does not occur. If preparedness is found wanting, a multitude of systems may be stressed. Leadership at national, regional, and local levels could benefit from the capability to institute infinite gaming exercises (a variation of the more traditional red flag scenario testing) involving truly capable players. Rather than adopting traditional bureaucratic responses like thematic reviews or establishing a task force (implying organisational boundary responses), we advocate developing some form of cross-disciplinary strategic gaming centre. This could act as the resilience ‘games room’ for national alertness and responsivity. Products from such a research hub would include advice and material on developing effective data strategies to foster better anticipatory reasoning. The hub would support and inform leaders about viable systems of preparedness.

Predictions using data or digital twins may be considered useful, but they can also create false impressions of reality. Iterative games challenge the assumptions of playbooks and standing orders, especially those which can hide the ‘black swans in the overgrowth’ (Beckford 2022). In such real games, all players, including adversaries and other parties, are free to define their own roles. None can determine the rules as there are no rules other than those set by one party upon themselves. Again, this makes prediction and modelling more challenging. The ‘real world’ outcomes of any infinite and asymmetric game are often increased effort and costs, which are themselves possible national resilience matters. Attempts by leaders to ‘win’ will generate costs without victory. Threats have their own meta-systems and sub-systems. They are morphogenic by following their own evolutionary pathways. They are mutagens which make national preparedness a complex challenge.

Conclusion

We stated at the outset that a different mindset to that which created the prevailing bureaucratic, functional command-and-control structures, will be essential in realising the effective use of data in developing national preparedness. The structure of governance and decisions; national, regional, local and individual, relies on information which has been derived from data. Strategies for preparedness are required to cover the full data lifecycle. Dealing with the continuing societal data tsunami, which is overloaded with variety, needs competent and confident leadership of data, information, and knowledge systems.

More research is required. However, this cannot be used as an excuse for insufficient application of current capabilities to emerging problems. Scenario-planning can be linear, but our complex systems are not; environmental and geopolitical variety is predominant. It follows that an aggregation of data across systems, and of a ‘games’ approach to surface potential threats, can assist. This will necessitate pragmatism and the logical abductive reasoning of common-sense truths.

A common well-defined, prudent, and meaningful language to describe data for preparedness would be a national asset. Potentially, leaders from diverse sectors could share and develop this lexicon within a dedicated gaming/knowledge hub.

In short, we need to frankly examine the failures and challenges of our current ways of working and understand the opportunities offered to us through the increasing availability of data. We need to develop means of structuring and organising these data to inform decisions. Such decisions will, in turn, rely on us understanding the value of knowing what others, including the population at large, value in a crisis. Only then can we address their concerns and issues in systems that work for those they are designed to serve. The next paper in this series will explore systems failure and its implications for national preparedness.

Further Reading

We have referenced a number of studies and research papers in this article. Those who want to dig more deeply into the topics discussed may be interested in the following sources (see numbered references below):

- There are recorded examples of knowledge-based innovation across many eclectic systems which can support effective practice. Consider a few examples such as McChrystal (10), Nonaka et al (11–13).

- A capability stack for adaptive organisational systems has been developed by Berry (8). This has been tested through gaming exercises with strategic leaders from security environments.

- Swarming AI is showing that new techniques for extracting data to create insight are possible. For example, in a smart contract/distributed ledger setting. The trick will be to consider both searching for patterns of events and non-patterns and anomalous data events. Technology that adopts encryption methods which guarantee the privacy of people will be key to developing citizen trust in such systems. (14–16) (17).

- Other elements of preparedness also fit within national policy frameworks, like the Strategic Policing Requirement (SPR), but in policing this no longer plays on centre court. The last published statutory inspection of the SPR appears to be in 2014 and the most recent Home Office publication appears to be 2015. What has happened to the SPR in the last seven years? (18,19).

References

The following references have underpinned the ‘bricolage’ of knowledge presented in this paper:

1. Taleb N. The Black Swan: The impact of the Highly Improbable . New York : Penguin Random House ; 2007. That which could have been foreseen but was not recognised or discounted.

2. Beckford J. The Intelligent Nation : how to organise a country. 2021;170. Cybernetics and transforming public services.

3. Without a trace: Why did corona apps fail? | Journal of Medical Ethics [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 3]. Available from: https://jme.bmj.com/content/47/12/e83 Lessons concerning cybernetics of data and systems in the pandemic.

4. Wiener N. Cybernetics; Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine ; . 2nd Ed. Paris and Cambridge Massachusetts and, MIT Press ; 1961. Classical cybernetic theory.

5. Beer S. Designing Freedom. 1993. Essays on cybernetic transformation.

6. Sinek S. The Infinite Game. Penguin Random House; 2019. Infinite games as strategy.

7. Carse J.P. Finite and Infinite Games. New York: Free Press; 2012. Infinite games in life strategy.

8. Berry R. Transforming to Polis 2.0, PhD thesis, Loughborough University; Research on data, transformation and strategy.

9. The Paradoxical Black Swan in the Overgrowth – Beckford Consulting [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 9]. Available from: https://beckfordconsulting.com/intelligent-organisation/the-paradoxical-black-swan-in-the-overgrowth/ Anticipatory reasoning to identify black swans.

10. McChrystal Stanley, Collins Tatum, Silverman David, Fussell Chris. Team of Teams – New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. Penguin Random House USA; 2015. Adaptive Change in a challenging context.

11. Nonaka I, Lewin AY. A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation. Source: Organization Science. 1994;5(1):14–37. Developing knowledge in organisations.

12. Nonaka I and Kommo N. The Concept of “Ba”: Building a Foundation for Knowledge Creation. California Management Review . 1998;40–54. Developing knowledge in organisations.

13. Nonaka I and Takeuchi H. The Knowledge Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995. Developing knowledge in organisations.

14. Saldanha OL, Quirke P, West NP, James JA, Loughrey MB, Grabsch HI, et al. Swarm learning for decentralized artificial intelligence in cancer histopathology. Nature Medicine 2022 28:6 [Internet]. 2022 Apr 25 [cited 2022 Oct 31];28(6):1232–9. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-022-01768-5 Developing knowledge through distributed networks and swarm intelligence.

15. Lester Saldanha O, Quirke P, West NP, James JA, Loughrey MB, Grabsch HI, et al. Swarm learning for decentralized artificial intelligence in cancer histopathology. [cited 2022 Oct 31]; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01768-5 Developing knowledge through distributed networks and swarm intelligence.

16. Saldanha OL, Muti HS, Grabsch HI, Langer R, Dislich B, Kohlruss M, et al. Direct prediction of genetic aberrations from pathology images in gastric cancer with swarm learning. Gastric Cancer [Internet]. 2022 Oct 20 [cited 2022 Oct 31]; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36264524 Developing knowledge through distributed networks and swarm intelligence.

17. Hayek E A. The Constitution of Liberty The Definitive Edition . 1st ed. Hamowy R, editor. Abingdon : Routledge ; 2011. A focus on freedoms within the context of the State.

18. Strategic Policing Requirement inspections – HMICFRS [Internet]. [cited 2021 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/our-work/article/strategic-policing-requirement/ Preparedness?

19. The Strategic Policing Requirement. 2014 [cited 2022 Nov 3]; Available from: www.hmic.gov.uk Preparedness?