A team of Master’s students in Cambridge University’s Engineering for Sustainable Development programme have undertaken some analysis on regulation and resilience, responding to a broad question set by NPC. Their work has highlighted the importance of a coordinated and consistent approach to regulatory oversight for enhancing food security, as summarised in this article. Team members were Ahmad Helmi, Caroline Hope, Han Mei Saw, Ishwar Gurung and Zeba Khalid.

What role do regulators play in enhancing UK’s food security?

Food security is under threat in the UK. The importance of this cannot be understated because of the role food plays in national resilience and preparedness.

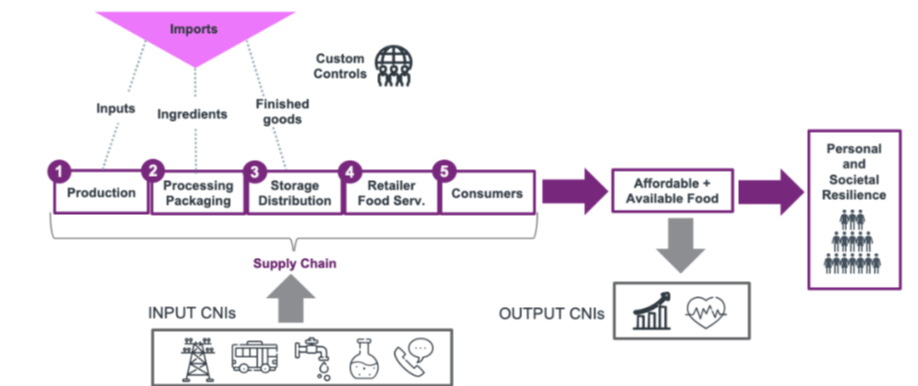

The challenge of food security, i.e., access to safe and nutritious food, needs to be addressed to strengthen the UK’s capacity to withstand various risks and shocks. Resilient food systems that provide affordable, high-quality food, both improve societal health outcomes and reduce vulnerability in the face of adversity. The modern UK food system and its supply chains are complex; relying heavily on imports and numerous sectors (including several critical national infrastructures- CNIs) to ensure food is delivered from farms to consumers (Figure 1). This year, interconnected risks such as climate change, geopolitical conflict and an energy crisis, have exposed the fragility of the UK’s food supply chains, evident through the reduced availability or affordability of locally produced and imported food.

As highlighted in the National Food Strategy, nutritious meals have the potential to alleviate existing obesity-related pressures, which can in turn enhance the resilience of the UK’s healthcare system.

Figure 1. The UK food supply chain and its relationship with other CNIs.

Input CNIs – electricity, transport, water, chemicals and communications; output CNIs = economy and health.

How do regulators respond these risks to strengthen our fragile food supply chains and maintain food security?

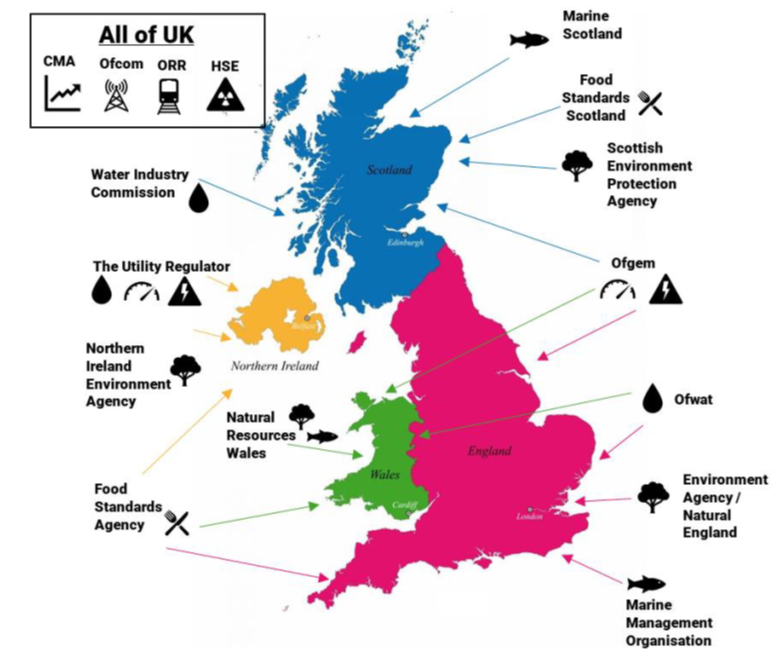

Different regulators exist across the food ecosystem and associated sectors, each with a unique combination of mandates, powers, stakeholders and remits (Figure 2). The systems analysis supporting this article revealed these inconsistencies contribute to a complex regulatory environment leaving potential vulnerabilities and gaps necessary for strengthening food security.

Figure 2: Variations in Regulatory Bodies across Four Nations

How could regulators incorporate resilience thinking for enhancing food security?

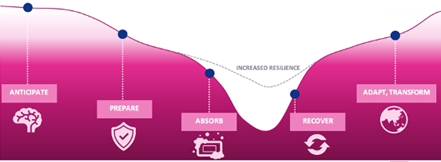

Resilience is useful in addressing the cyclical nature of shocks and stresses; it can be conceptualised through five main stages (Figure 3). These stages encompass the proactive measures taken to anticipate and prepare for potential shocks, the capacity to absorb and mitigate the impacts when they occur, the ability to recover from the aftermath, and finally, the flexibility to adapt and transform in response to changing circumstances. Regulators are increasingly recognising the importance of resilience, however to date, their focus lies in the Anticipation phase of the resilience lifecycle (Figure 3). This aligns with their current responsibilities. Increasing food supply chain resilience likely requires coordinated input, planning and action across each phase as demonstrated in the following case study.

Figure 3. Phases of Resilience Life Cycle (Adapted from NIC report)

Case study: 2007 flooding event

A system-led analysis of this event, viewed through the lens of resilience, looked at the consequences of the flooding event and its cascading impacts on the capacity for local food production and the cost of farming. Short and long-term impacts have a negative impact on food security:

- Short term: accessibility and affordability of food decreases and reliance on food imports increases.

- Longer term: flooding negatively affects soil quality and biodiversity, resulting in decreased food production and potentially triggering a decline in the economic value of agriculture, which could contribute to rural exodus, further reducing local production capacity.

The UK’s agriculture sector will continue to be susceptible to climate change-related risks such as floods, with some farms having a greater degree of vulnerability than others. To build resilience, regulators such as the Environment Agency and the Financial Conduct Agency, will need to collectively decide on a system for the distribution of financial services for:

- the short term i.e., disaster relief in the Absorb and Recover phases

- the long term i.e., ongoing lending from banks in the Adapt/Transform phase

For example, in the long term, both agencies will need to consider the varying climate change-related risks across the UK farms. Those more resilient are encouraged to remain in business through sustainability-linked loans for environmental improvements, and those deemed unsuitable for farming will require financial support for a just transition away from the sector.

This case study highlights that a systems view is required to understand how regulators with seemingly distinct responsibilities would need to collaborate to ensure resilience. The analysis more generally sheds light on the gaps in regulatory bodies’ involvement and provides insights into collaboration opportunities. Regulators would benefit from clearer guidance on their responsibilities throughout the resilience cycle to minimise gaps and ensure a comprehensive approach to food security.

Takeaways

The following three complementary concepts concerning food security are key:

1. Food security is a fundamental component of national resilience and safeguarding the well-being of the population.

2. Regulatory bodies play a vital role in establishing a resilient food ecosystem, but this requires collaboration and transparency in the complex regulatory landscape.

3. Systems thinking is a valuable tool for analysing challenges and revealing opportunities across sector boundaries, where collaboration could strengthen the food system.