Enhancing Warnings

About this report

Published on: January 7, 2022

Warnings are not just a siren or phone alert but should be a long-term social process that is a carefully crafted, integrated system of preparedness involving vulnerability analysis and reduction, hazard monitoring and forecasting, disaster risk assessment, and communication.

This report makes key recommendations about how warnings can be made more effective in the UK.

Authors

Dr Carina Fearnley, UCL Warning Research Centre

Professor Ilan Kelman, UCL Warning Research Centre

Executive Summary

Background

Warnings are part of our everyday life, whether traffic lights, food health warnings, the weather, advice from colleagues, or moralistic stories. Warnings serve to provide cautionary advice, give advance notice of something, and generate awareness to trigger consequent decisions and actions. Warnings are seldom considered beyond the issuance of a warning, yet warnings are far more complex, requiring a comprehensive tool and system to help implement preventative, mitigative, and disaster risk-reductive actions. This report offers insights into what warnings are and how they can better support actions for effective behavioural preparedness and responses across a wide range of hazards, stakeholders, and sectors.

Warnings are not just a siren or phone alert but should be a long-term social process that is a carefully crafted, integrated system of preparedness involving vulnerability analysis and reduction, hazard monitoring and forecasting, disaster risk assessment, and communication. Together, these activities enable a wide range of leaders and others – such as individuals, local groups, governments, and businesses – to take timely and effective action to reduce disaster risks in advance of hazards. Warnings are represented via different iconographies and communicated via different mediums that usually express some form of threshold or tipping point. These vary enormously contingent on the hazard, and social, political, and economic context of the warning.

Warnings should provide actionable guidance that is integrated into everyday life and behaviour, providing transparency and credibility to help manage risk in emerging and ongoing situations. Warnings must operate beyond the silos frequently seen in institutions, for different vulnerabilities, different hazards, and different stakeholders to become a long-term social process that can serve to bring together these diverse issues. This report examines how this can be implemented providing key case-study examples of lessons learnt and guidance on how to build effective warning systems.

To enhance a warning requires placing it as part of a warning system, a long-term social process that embodies the 3 I’s and 3 E’s:

3 I’s: Imagination, Initiative, Integration.

3 E’s: Education, Exchange, Engagement.

Key Recommendations

Three key actions are recommended to enhance warnings in the UK:

Develop effective warnings that consider multiple-hazards, cascading events, and integration across stakeholders.

- Build effective warnings by adopting four key characteristics: accuracy, flexibility, timeliness, and transparency.

- Design warnings to be flexible and faciliate multi-directional feedback.

- Ensure alert level systems include communication protocols, the level of standardisation, and the decision-making processes.

Adopt a public engagement and outreach programme that empowers people to identify and fulfil their own needs regarding warnings for enhancing preparedness and response behaviours and actions.

- Combine education, exchange, and engagement to help integrate top-down and bottom-up approaches to policy development and community

Create and support mechanisms to overcome silos and territorialism and instead encourage idea and action exchange for building trust and connections that support action when a major situation arises.

- Develop a warning expert committee

- Use the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) for independent and transparent advice.

- Develop training and exercise programmes for warnings.

- Integrate successful public engagement lessons.

This report provides guidance on how to implement these recommendations.

Overview of Warnings

When a fire alarm is triggered, most people look around to check whether it is a drill or an error. The warning is there, the evacuation signs are clear and routes to safety are established. Yet, many do not want to interrupt their activities and instead seek additional information or assurance to guide their subsequent actions. Whilst failing to evacuate immediately can cost lives, the ability to understand, reaffirm and act on the situation goes beyond the siren and strobe light. A lack of action is a lack of engagement, often emerging due to a lack of imagination regarding why the warning exists along with a lack of initiative in leading behaviour.

Warnings are a vital component of disaster risk-reduction activities for all forms of hazards, vulnerabilities, and risks. They are an effective tool to communicate hazard and/ or risk and generate appropriate action that is currently being under-utilised globally. Warnings save countless lives every year, can be used to support day-to-day living and vulnerability reduction, and are often operated by government organisations with legal remits to increase resilience.

Why Warnings Matter

Failure to implement effective warnings can result in significant loss of life and socio-economic impact:

- Over 250,000 people (including 149 UK citizens or people with close ties to the UK) died in the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami as the region lacked a formal tsunami warning system despite decades of efforts to create In this case, no official warning was issued, so the people who needed to evacuate were not informed, demonstrating a lack of integration between scientific warning information with the people directly affected.

- Over 22,000 people died in 1985 from mudflows after the Nevado del Ruiz volcano in Colombia erupted despite detailed hazard maps being available and accurate warnings being issued by the In this case, the solid science and warnings were not accepted or acted on due to a lack of imagination in accepting the meanings of the scientific information.

- Over four million people (including over 140,000 people in the UK) have so far died in the Covid-19 pandemic despite sufficient information and clear warnings coming from China in January and February 2020 indicating the possibility of the disease being a major Warnings of a significant pandemic have been flagged for decades, yet preparedness actions were not fully in place due to a lack of initiative in leading pandemic readiness.

Boxes 1 and 2 provide examples of known threats with past catastrophes where work should be done now to ensure that warnings work and lead to needed action. Yet, frequently despite clear irrefutable warnings, the appropriate action is not taken.

Warnings are difficult to support for three main reasons.

Investment is needed to develop a long-term warning process and it is difficult to justify these financially as tacit impacts (e.g. cultural loss, mental health, trauma) from a disaster or event are hard to quantify in a cost-benefit analysis relative to measurable) impacts (e.g. infrastructure damage, business costs).

Precautionary approaches for warnings of a number of hazards may not be required in the short or medium term (e.g. a pandemic, asteroid), yet, when the event happens, the impact is highly costly. It is difficult to justify to taxpayers that money is being spent on events that may happen when money is needed to address definite needs. Yet, it has been proven that for every $1 invested in disaster risk reduction activities saves over $10 following the event. Policy makers tend to focus on timescales in line with political terms, rather than adopting more long- term investments that work beyond party politics, as seen in the challenges of heeding warnings of anthropogenically enforced global warming.

Awareness and research on warnings remains limited, disparate, and often focused on individual case studies with little opportunity to share and compare practices and knowledge. Warning science, policy and practice are also often compartmentalised by hazard or threat, without much cross-vulnerability connections. These elements can provide barriers to implementing warnings, despite their clear value.

Box 1: Storm Surge for London

Throughout the centuries, storm surge flooding from the North Sea has been a major concern for the UK. London has been flooded on many occasions by such surges and has also experienced flooding from rainfall via the River Thames and its tributaries as well as ponding in the streets. Following a devastating storm surge around the North Sea in 1953, including hundreds of deaths across the UK, a moveable barrage was built across the Thames downstream from London, The Thames Barrier helps to stop a storm surge propagating up the river into the city while also assisting with reducing rainwater flood intensity.

Because the Thames Barrier takes up to 90 minutes to close, warning for a storm surge is needed. Systems are in place to monitor possible storms, predict the storm surge and tide levels, and alert for the need to close the barrier – with approximately 36 hours of warning provided. The assumption is that both warnings and the Barrier will always work as expected, so there appears to be little need for flood awareness or preparedness. Consequently, flood vulnerability in London has increased.

First, floodplain use has expanded. One of the world’s financial centres, Canary Wharf, was constructed after the Barrier became operational. Many residential properties have been built with Thames views near and upstream of the Barrier; the underlying assumption is that these areas will not be flooded due to the Barrier. Second, warnings are not typically geared toward evacuating the floodplain. A low awareness exists among people living and working in central London regarding the flood potential. Even if warning and evacuation notices were issued, it is unclear how many people would know what to do and how many would act in a timely and safe manner.

Little incentive exists to take initiative on reducing flood vulnerability, because the Barrier is viewed as fully protecting London from floods. Consequently, warnings can be seen to provide a false sense of security if they are not integrated as social-processes with vulnerable populations.

Box 2: Flash Floods in Europe

In July 2021, around 200 people were killed in western Europe in flash floods. The floods seemed to have hit without warning, even though the European Flood Awareness System (EFAS) had given days of warning that intense floods were expected with many updates as the seriousness of the situation became increasingly apparent. This is another example of the science, monitoring, technology, and information being successful, yet still the warnings failed to avert a disaster, partly because those affected could not imagine the suddenness, intensity and danger of the floods. This despite many of the damaged places having long histories of flooding.

The UK is not immune to such a scenario. Lynmouth in 1952 and Boscastle in 2004 are examples of flash floods. If, as with EFAS, plenty of time is provided regarding the expected rainfall and flooding, would people in the areas warned have the imagination to realise what is coming, to accept the information, to know exactly what to do and to act? The only way of knowing for a specific location is to ask them. What do they know and what do they not know? What would they need and how could they lead improvements? What might change their behaviour to do better for themselves? Would they be willing to lead themselves for it and how much external guidance and support would be needed?

It is easy to point to a flash flood warning system and say that all the data, information and material are fine. It is not so easy to ensure that a flash flood disaster is averted. The people affected can best identify and close any gaps for themselves but no one can provide everything which means working together, pooling knowledge and linking bottom-up with top-down.

What are Warnings?

Warnings are tools and processes for turning knowledge and information into decisions and actions. Warnings are often considered within the context of an Early Warning System (EWS), defined by the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (2017) as:

‘An integrated system of hazard monitoring, forecasting and prediction, disaster risk assessment, communication and preparedness activities systems and processes that enables individuals, communities, governments, businesses, and others to take timely action to reduce disaster risks in advance of hazardous events.’

They are primarily a social process, often using technology and always integrated into and across all governance levels, from international to local, while combining formal and informal approaches. Warnings continually cover all disaster-related activities, requiring aspects of planning, preparedness, damage mitigation, education, training, risk reduction, recovery, and reconstruction.

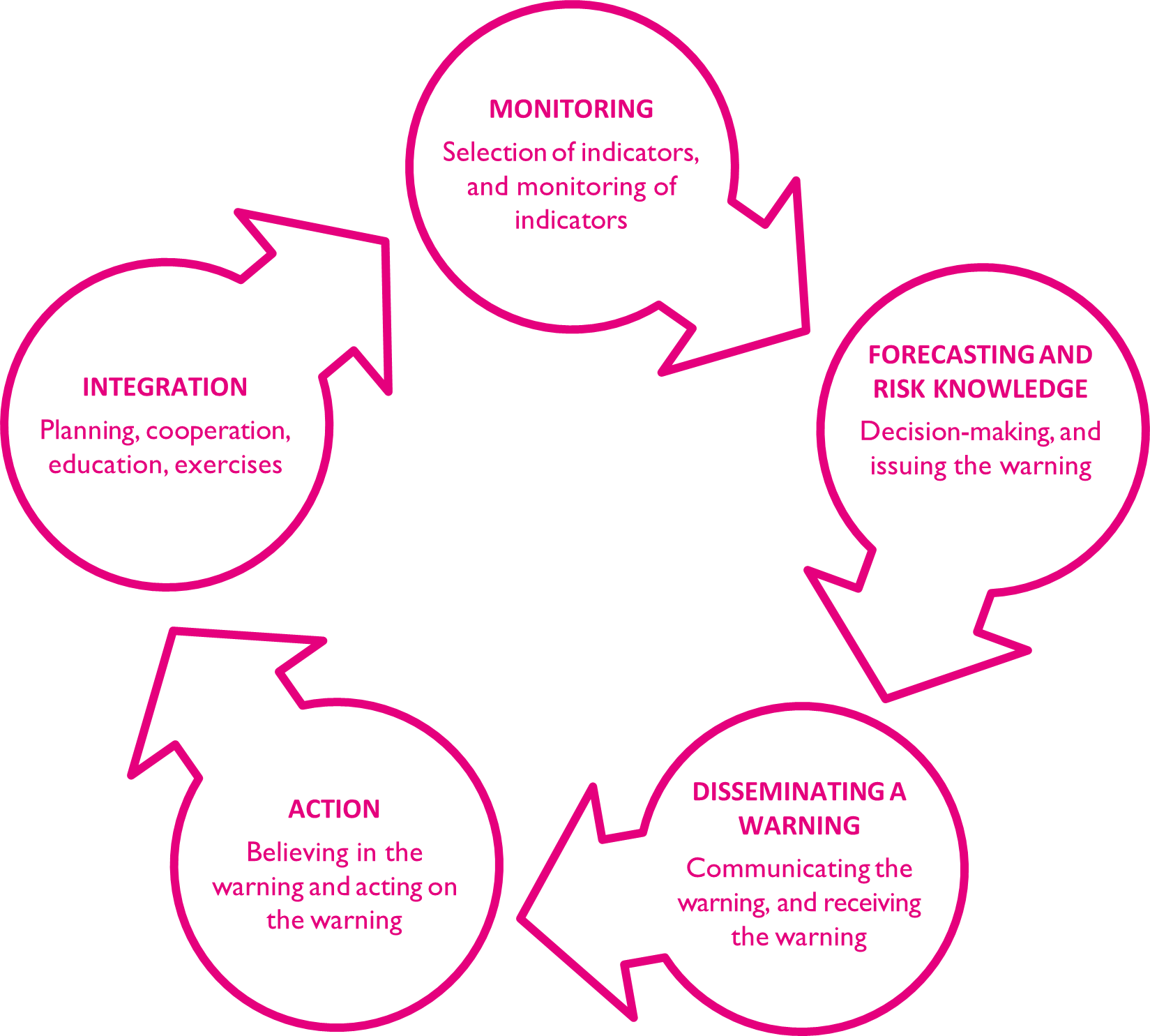

Warnings must translate into decisions and actions, otherwise they are not fulfilling their purpose. Warnings comprise of five key steps, each vital to the success of the warning issued:

Governance of Warnings

Paramount to warnings governance is establishing the leaders, decision-makers, and disseminators. Who has authority, responsibility, and accountability in warning matters; how do they enact their duties; and why do differences or disjoints exist?

Several institutional frameworks exist for warnings at differing levels:

- Local levels: Community-based or community-established warnings via groups such as the Red Cross and Red Crescent as well as local self-organisation, local level government warnings, and local immediate warnings, g. by COMAS (control of major accident hazards).

- National and sub-national governments: Government agency led warnings such as, for the UK, the Met Office, British Geological Survey (BGS) and the Environment Agency / Scottish Environment Protection Agency (EA / SEPA).

- Global or regional organisations: Global organisations such as the United Nations, the World Health Organization and the World Meteorological Organization.

To develop clear governance of warnings, three key responsibilities must be established:

- Legal responsibility: The responsibility to provide warnings depends on laws. In the UK, scientists typically assess vulnerabilities and hazards, with government officials making decisions around suitable responses to the data presented or absent. In some instances, such as in the Philippines, Indonesia, and in some processes such as Climate Outlook Forums, this process is combined, working together to interpret the information and to generate decisions although legal liabilities may depend on specific contexts.

- Clearly defined roles and responsibilities: This requires political commitment to generate legal, policy and implementation frameworks to facilitate and support warning processes, investment in capabilities and co-ordination among everyone involved.

- Integrated as a daily responsibility for the community: To make warnings fully effective, they need to be part of regular activities contributing to daily life and livelihoods while being continually updated to account for changes (see Box 5).

Good practice examples of integrating many such elements, including the first mile, are hurricane warnings and evacuations for the US and Cuba (as with Box 3 for Bangladesh). Despite very different governance systems, both countries have long had successful monitoring and projection of hurricane tracks following by millions evacuating to safer ground. Hurricane damage remains extensive but deaths have declined from thousands to dozens per storm, even as coastal populations have substantially increased. A focus on hurricanes can, though, distract from other hazards, with hurricane-related tornadoes seeming to be ‘surprising’ because the warning and evacuation notice was for hurricanes. In fact, warnings from different hazards and threats often operate in isolation and lack the capacity to identify and manage concurrent and cascading crises, whereby an initial event’s impact can generate a sequence of subsequent failures and disruptions, often worse than the initial event. Lessons from several simultaneous large-scale crises, including COVID-19, human-caused climate change, terrorism, and poverty highlight the challenges in developing fully integrated warning systems. The UK frequently experiences these situations such as in 2001 with floods, foot-and-mouth disease, and petrol shortages, and also in 2021 with a pandemic, food shortages, gas-supply problems and petrol shortages again. This raises questions about how warnings can work across governmental silos to address multi-hazard and cascading events.

Box 3: Bangladesh Cyclone Warnings

The coastlines of Bangladesh are low-lying, subject to devastating storm surges from cyclones making landfall from the Bay of Bengal. Hundreds of thousands died in a cyclone in 1970 followed by tens of thousands in another storm in 1991. Over the past few decades, the country has been battered by further cyclones but these killed dozens or hundreds.

This massive reduction in death toll was affected by engraining cyclone warning and response within the local culture and linking it to day-to-day life. People receive local warnings, know where to evacuate to, and are confident that a good proportion of their livelihoods will remain afterwards, even while they are rebuilding. Local training for cyclones is linked to developing household businesses, creating local markets for goods, mapping difficulties and dreams in the community and training for first aid and search-and- rescue. Many of these activities might not seem to be typical for warnings but they integrate and connect with the wider warning system and warning process to improve daily life and livelihood continually, connecting people to the warnings and enhancing appropriate action.

These successes do not guarantee an absence of disasters. Mistakes could happen for a cyclone, plus Bangladesh is highly prone to river floods, earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides and other hazards. A key lesson is that warning is a continual societal process because past success does not guarantee future success, while multiple hazards need to be considered.

Current Operation of the UK Warnings

In the UK, warnings are commonly issued via individual or joint agencies responsible for a key hazard that takes leadership around the particular hazard e.g. flood warnings by the Flood Forecasting Centre (FFC) (partnership between the Environment Agency and the Met Office) and terrorism threat levels by the Joint Terrorism Analysis Centre and the Security Service (MI5). Whilst these warnings exist within their own silos, Category 1 responders (organisations at the core of the response to most emergencies, such as the emergency services, local authorities, and NHS bodies) are subject to the full set of civil-protection duties as outlined in the Civil Contingencies. Act 2004 (section 4, 20, p12) including:

‘Arrangements to warn the public, and to provide information and advice to the public, if an emergency is likely to occur or has occurred’.

These arrangements are typically implemented via a Public Warning Task Group that works within Local Resilience Forums (multi-agency partnerships made up of category 1 and 2 responders). Whilst there are numerous examples of Local Resilience Forums establishing effective warning systems, challenges emerge within and beyond these specific structures:

- Warnings are often issued at a national level, with Local Resilence Forums working to apply them at their However, co-ordination and communication between Local Resileince Forums can be challenging, and it remains problematic to obtain visibility for all the national warnings issued as they remain under different responsibilities.

- Warnings are typically focused around one hazard or threat occurring at a time rather than a multi-hazard or cascading crisis, with vulnerabilities often neglected.

- Managing a nation-wide crisis, such as COVID-19 starting in 2020, or volcanic ash that shut down much of European airspace in 2010, is complex as issues cross local coordination groups and the four nations have differing approaches.

- Warnings become more responsive than anticipatory, not enabling stakeholders enough time to respond effectively to the This is partly due to a lack of resources and few long-term staff to develop preparedness actions.

Previously, the UK’s National Steering Committee on Warning and Informing the Public provided primary independent advice to the Cabinet Office on best practice for warning and informing the public during an emergency or major incident. It was last publicly active in 2013.

On a national level there are challenges in integrating relevant expertise and warning for long-term or low-frequency but high-impact events. At present, there are few formal mechanisms to integrate external expertise from academics, NGOs, businesses, and others into decision-making processes. Key communication networks have no central location to obtain the latest and credible government issued advice, typically provided in an emergency operations centre. Often, the public and their knowledge is left out.

An example is the radioactive fallout impacting sheep farming in Cumbria following the Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster in 1986 during which adopting top-down narratives that ignored local expertise proved costly. Wynne (1992, 1996) studied how government scientists claimed the problem would clear up in weeks, taking little account of the area’s specific features and contradicting the farmers’ own expertise. This top- down approach undermined the status of local knowledge, creating disillusionment about scientists’ ability to predict, manage and inform about risks. Wynne’s work first highlighted ‘the forms of institutional embedding, patronage, organisation and control of scientific knowledge’ (Wynne, 1992, p42) that often lead to a lack of action by the public in response to warnings, followed by blaming the public for not acting.

All the pieces needed for effective UK warnings exist already, including information, interest, knowledge, experience, data, messages and communication mechanisms. Numerous, specific examples of successes and failures can inform improvements. Yet, appropriate behaviour is still often absent and leadership failures at all levels are too evident in terms of decision-making and behaviour. The focus for policy options and recommendation to enhance warnings in the UK should be focused on getting warnings right based on what already exists, rather than trying to trying to change well established mechanisms and therefore undermining the solid, established, and accepted elements. UK warnings should comprise of the five principles in Table 1.

| Principle | Implementation and Process | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Warnings are

long-term social processes. |

They need to be integrated into short-, medium-, and long- term plans and societal structures that are able to use warnings for appropriate actions. | UK supply chains were disrupted by the 2011 Bangkok floods, the 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami, and the 2021 Suez Canal blockage.

Planning could have led to short-term substitutions as well as long-term alternative sourcing once warnings were available, if those affected had been preparing long in advance for such situations. |

| Warnings must use multiple channels

/ modes and be clear, transparent and credible. |

Some people rely on WhatsApp or Twitter for news; others use neither. Not everyone can see, hear, or read. Users

will be left out without creativity, flexibility and trust across multiple communication and engagement modes. |

Public buildings should have fire alarms which are both audio and visual. For places where people sleep, such as hotels, mechanisms are needed to alert people with hearing impairments. |

| Warnings must

be relevant to everyone, covering a range of timeframes and spatial coverage. |

If people cannot afford to evacuate – or to plan for evacuation – then warnings might not be helpful. | Many who evacuated from the Grenfell Tower fire in London in 2017 spent months in ‘emergency accommodation’,

effectively being in limbo. What would they have done if it had been 2.5 years later and suddenly warnings of a pandemic and possible lockdowns were in force? |

| Warnings need

to connect all governance levels, including local, national and international. |

Cybersecurity affects everyone, from individuals losing

life savings through phishing through to health services and multinationals held hostage to ransomware. Cybersecurity warnings need to connect all these users. |

Some phishing examples are highly localised and culturally contextual, such as using recent news stories in local languages. Others are international, when viruses spread around the world. |

| Warnings require integration

across different vulnerabilities to respond to multiple hazards, sequences and cascades. |

They need to be integrated and co- ordinated across differing silos to enable broader, more diverse overviews of any single situation or multiple crises. | A small area flooded in south-eastern England could mean that several train drivers cannot get to work, leading to cancelled trains and government workers unable to reach their desks. In July 2021, the COVID-19 test-

and-trace system told many airport workers to isolate, leading to major delays for Heathrow passengers. |

Key Recommendations for Warnings

This section provides three key recommendations for developing warnings and warning systems that generate effective actions, building on the state of the art. The aim is to provide guidance on how to achieve these recommendations via practical actions and decisions.

Three key actions are recommended to enhance warnings in the UK:

- Develop effective warnings that consider multiple-hazards, cascading events, and integration across stakeholders.

- Adopt a public engagement and outreach programme that empowers people to identify and fulfil their own needs regarding warnings for enhancing preparedness and response behaviours and actions.

- Create and support mechanisms to overcome silos and territorialism and instead to encourage idea and action exchange for building trust and connections that support action when a major situation arises.

1. Building Effective Warnings

To plan, develop, and maintain effective warnings there are four key characteristics that need careful consideration to facilitate warning success:

A | Accuracy

Warnings deal with hazards and threats that have differing levels of predictability, often obtaining more certainty the nearer the danger. Given the inherent uncertainties in issuing warnings, confidence that warnings are accurate and will not cause false alarms or potential warning fatigue can vary. Box 4 on climate change warning indicates the importance of accuracy, and specifying the uncertainties involved.

Box 4: Climate-Change Warning

Human-caused climate change has been a major scientific concern since at least the 1970s, leading to efforts in subsequent decades for concerted international policy action. Despite this long-term warning of adverse impacts, effective international action remains absent. Misinformation, disinformation and intransigent countries and corporations are significant reasons. Another factor is inaccurate warnings such as on climate change causing disasters, conflicts and migration. Warnings about millions of ‘environmental refugees’ and ‘climate refugees’ became popularised in the mid-1990s with variations including a 2005 warning about 50 million by 2010 and then a 2010 warning about 50 million by 2020.

Reality did not match these dire warnings, undermining supposed links between climate change and migration. Yet, warnings of ‘climate-change migrants’ continue to be publicised, despite the absence of scientific evidence for the warnings alongside many scientific analyses providing fewer alarming conclusions. Caution is needed in attributing migration (as well as disasters e.g. from hurricanes, and conflicts such as the Syrian war) to human-caused climate change, although heat-humidity is projected to be a significant exception and other scenarios exist which are devastatingly catastrophic. Warnings about the adverse impacts of human-caused climate change need to retain scientific accuracy for both horribly disastrous and exaggerated outcomes.

B | Flexibility

Warnings are not technological instruments but are social processes that allow for differing approaches, whether formal or informal, international, or local, qualitative or quantitative, and high-tech or low-tech. Warning design and dissemination needs to reflect the flexibilities involved in dynamic and intertwined societies and environments.

C | Timeliness

The time between the hazard or threat detection and the outcome prediction (more specific) or projection/forecast (vaguer) gives the lead time to prepare and varies enormously. A hazard itself can last for differing timescales, from seconds of a bomb blast to decades for volcanic eruptions. Many warning processes involve large-scale operational systems (see Box 5).

D | Transparency

Openness of and communication regarding data collection, leadership, and decision- making processes around warnings influence people’s trust and hence behaviour. Warning decisions and actions should be audited and held to account, not necessarily to blame and punish, but rather to share reflections and lessons in order to improve. Where authority, responsibility and accountability are poorly connected, transparency becomes difficult, and leadership loses trust.

Box 5: Tsunami Warnings

Formal warnings for Pacific Ocean tsunamis started in 1949, leading to international co-ordination in 1960. Similar proposals were made in the 1970s for Indian Ocean tsunami warning. Despite decades of effort, Indian Ocean tsunami warning was always deemed to be low priority until the 2004 catastrophe after which the Indian Ocean tsunami warning system was operational within 18 months. Now, poor maintenance and lack of upgrades are causing problems, especially for near-shore tsunamis such as the waves from a volcanic eruption and collapse in Indonesia in December 2018. Lessons from Indian Ocean tsunamis are quickly being forgotten including anecdotes from 2004 where a single person’s observations or a community’s collective knowledge of the sea’s odd behaviour led to rapid evacuations and thousands of lives being saved.

It is the same with UK tsunami warnings. From hazards such as an oceanic landslide in the Canary Islands, a suggestion which re-emerged during the 2021 eruption of La Palma’s Cumbre Vieja volcano, or under the North Sea, UK coastlines have immense tsunami vulnerability as evidenced by the extensive infrastructure in potential tsunami inundation zones, low awareness among the population regarding the possibility, and little scope currently for effective warning and action. With major tsunamis in living memory having occurred only in faraway places, tsunami disasters are not seen as being an important UK concern. Few people living in vulnerable places would receive a warning of impending inundation or know how to act.

These four characteristics combine to show the importance of effective warnings being:

Integrated

Warnings should be understood not just for their differing components, but also as a system where the links between the different components facilitate action, typically as a warning system. Successfully integrated warnings connect internationally through to local levels by displaying:

- Trust and credibility;

- Clearly defined authority, accountability, and responsibility;

- Education, training, and communication;

- Research, knowledge, and engagement;

- Exchange of ideas, knowledge, and expertise;

- Imagination and initiative to learn and act on the learning.

Ultimately, warning users must be integrated into the entire warning process so that they have the imagination to take the initiative on turning knowledge and information lead to decision and action. Integration cannot be started during a crisis as it is then too late. Instead, warnings are a continual, integrated process involving collective education, exchange and engagement which leads to imagination and initiative. A warning system must be managed as an ongoing concern.

Achieving this success requires everyone. Too often, warning failures are seen as needing to close the so-called ‘last mile’ representing gaps between the origin of warning information and users. Instead, the warning process must prioritise the ‘first mile’ representing a beginning with users to listen to and respond to their needs and contributions.

Designing Warning Systems

Designing a warning system is a complex process given the diversity of experts, hazards, threats, and policies involved. Warning systems are too frequently linear, top-down processes, assuming that expert information goes from a centralised source to the inexpert masses. They should instead be networks of connected elements in which everyone is involved in the design, maintenance, operation, and use. Effective warning systems enable multi-directional feedback and are flexible, always changing according to people’s needs.

Designing the warning process requires establishing:

- What is the purpose of the warnings?

- How can everyone involved be connected and contribute?

- How are decisions and disseminated? By whom?

- Who leads? Who is responsible? Who is accountable?

- What methods would be most appropriate for the entire process?

- What behaviour or actions are needed from the warnings?

- How will the warnings be tested, monitored, and evaluated for continual improvement?

- How do the warnings integrate with warnings for other hazards, and international level warnings?

Warning systems can be formed in different ways depending on the focus, purpose, and resources available, providing different communication mechanisms. When designing a warning system, it is important to consider the type of system to be implemented, and how existing international warning systems already exist that can be integrated.

International warning systems:

- The Common Alerting Protocol (CAP): This alerting system is implemented globally to provide an international standard format for emergency alerting and public warning via technology and radio.

- Earth Observation Systems (EOS): Numerous warning systems for hazards rely on deployed sensors on or near the Earth’s surface or on satellites to track changes in the environment, be it a short-term volcanic eruption with volcanic ash, or longer- term impacts such as deforestation or sea-level rise.

Types of warning system:

- Integrated warning systems: These systems bring together data, analysis, warnings, and response in one system as seen in the Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS).

- Community-based warning systems (CBEWS): These systems empower people by involving them in the data collection and analysis processes, with communities leading and operating them.

- Traditional warning systems: These systems incorporate traditional knowledge and observations, often through storytelling, songs, and regular conversations about the local environment.

- Multi-hazard early warning systems (MHEWS): These systems facilitate co- ordination and consistency of warnings for multiple hazards occurring simultaneously or in succession, as differing actions may be required.

- Automated warning systems: Once established these technologically based systems operate without human input to provide warnings based upon pre-assigned criteria and may trigger automated responses (e.g. bridge closures).

Alert Level Systems

Warnings are commonly issued using Alert Level Systems (ALS). ALS are used globally as a shorthand to convey concise and clear information to a wide range of users. They often follow a traffic light colour structure or numerical order (as commonly used in military contexts), and can be standardised across governance levels and entities.

While ALS are commonly thought of as simple ‘triggers’, to be effective they must be embedded in an extensive system of:

- Observation and communication that integrates different experts;

- Thresholds or tipping points;

- Communication mediums and iconography.

The provision of timely warnings to public and civil authorities can be used to gauge and co-ordinate response to a developing emergency. ALS provide public awareness about both escalating and deescalating crises. Yet, there is limited research on the design, use and implementation of ALS. For some natural hazards such as volcanoes and tsunamis ALSs are well established, providing good operational guidance for developing much- needed ALS for other hazards (Fearnley, 2012; Fearnley 2013).

Decision-making:

- Whilst ALSs are used globally as visual and text-based shorthand systems to convey concise and clear information to a wide range of people, scientific uncertainties can make them complicated to use.

- The decision to change an alert level can be challenging due to difficulties in interpreting scientific data to establish what a hazard is doing, and how it may affect society.

- The decision to move between alert levels emerges from a detailed negotiation of perceived political, livelihood and environmental factors rather than solely the scientific This means considering the risks, not just the hazards.

Communication:

- ALS cannot convey the risks alone through a single alert so additional information is required to make sense of alerts issued.

- ALS can be effective in generating general awareness levels and acting as triggers for initial communication, policy, and action.

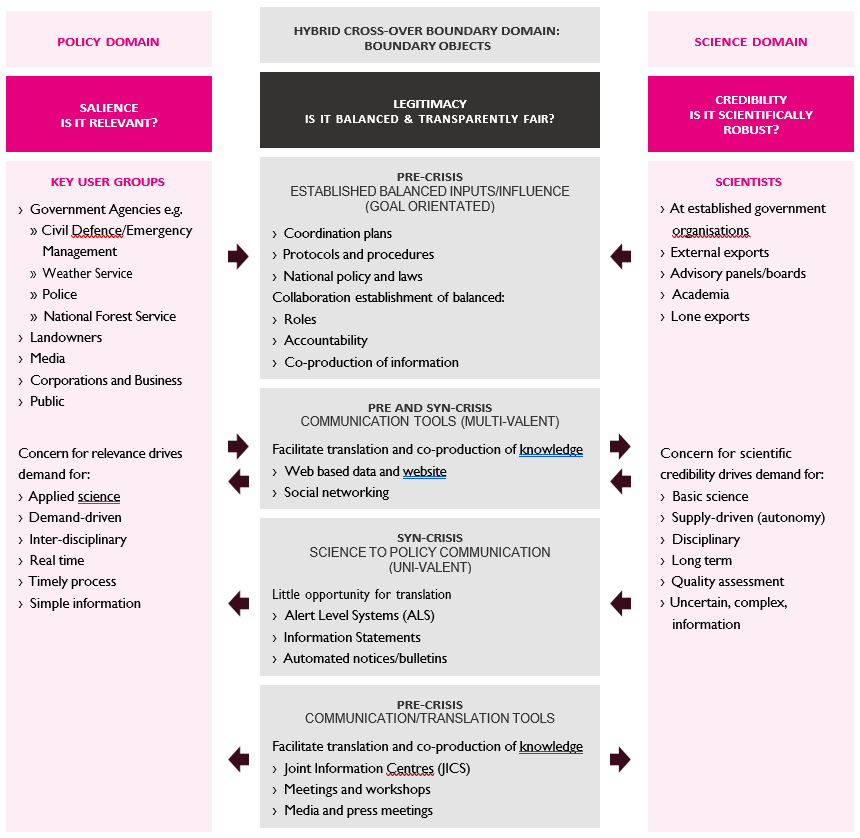

- Translation and interpretation through multi-way communication across multiple pathways ensure that everyone understands what information is credible, salient, and legitimate (see Figure 2).

Common communication tools and mechanisms used to create legitimacy between the scientists and key user groups include co-operation plans, protocols, and procedures. These activities depend on everyday dialogues in differing formats among users (e.g. social networks, email, phone and in-person) alongside the establishment of joint information centres JIC), meetings and workshops. Examples are the National Incident Management System (NIMS) emergency management structures used in the USA, New Zealand, and Australia.

It is vital that leadership from, preparedness by, and engagement with users occurs prior to a crisis as it is too late to start the process once a hazard or threat manifests. This enhances the actions taken in response to warnings.

Managing complexity does not need to be complicated, irrespective of all the unknowns and uncertainties. Effective leadership, communication and interaction overcome these challenges.

Standardisation:

- Standardising alert levels and warnings can convey information to a wide range of people, while always leaving behind some groups.

- The process of standardisation is shaped by cultural, political and livelihood factors rather than only in response to scientific needs specific to a hazard or to vulnerabilities.

- Consequently, standardisation is difficult to implement due to the diversity and uncertain nature of hazards and vulnerabilities at different temporal and spatial scales.

| Issues | Local

(Non-Standardised) |

National (Standardised system) |

| Users’ needs | Provides flexibility to local community but global users may be confused | Limits flexibility possible, but provides consistency and clarity to all |

| Communication Methods | Local interpretation likely to be more effective | Common terminology and understanding, but must be known |

| Decision Making | Gear decision on local needs, circumstances and knowledge | Descriptions provide guidelines / criteria, but implications may vary |

| Management | Local stakeholders develop close relationships | Streamlines communication within government agencies reducing confusion |

What Makes Warnings Successful?

A warning does not start with a hazard manifesting:

‘The most effective warning systems integrate the subsystems of detection of extreme events, management of hazard information, and public response and also maintain relationships between them through preparedness.’

(Mileti et al., 1999, pp174–175).

Warnings as a social process means that it should be ongoing, engrained in the day- to-day and decade-to-decade functioning of society – even while recognising that this ideal is rarely met in practice. To understand the operationalisation of this ideal for a warning and its system, the phrase itself needs to be broken down.

‘Warning systems are only as good as their weakest link. They can, and frequently do, fail for a number of reasons.’

(Maskrey & UN, 1997)

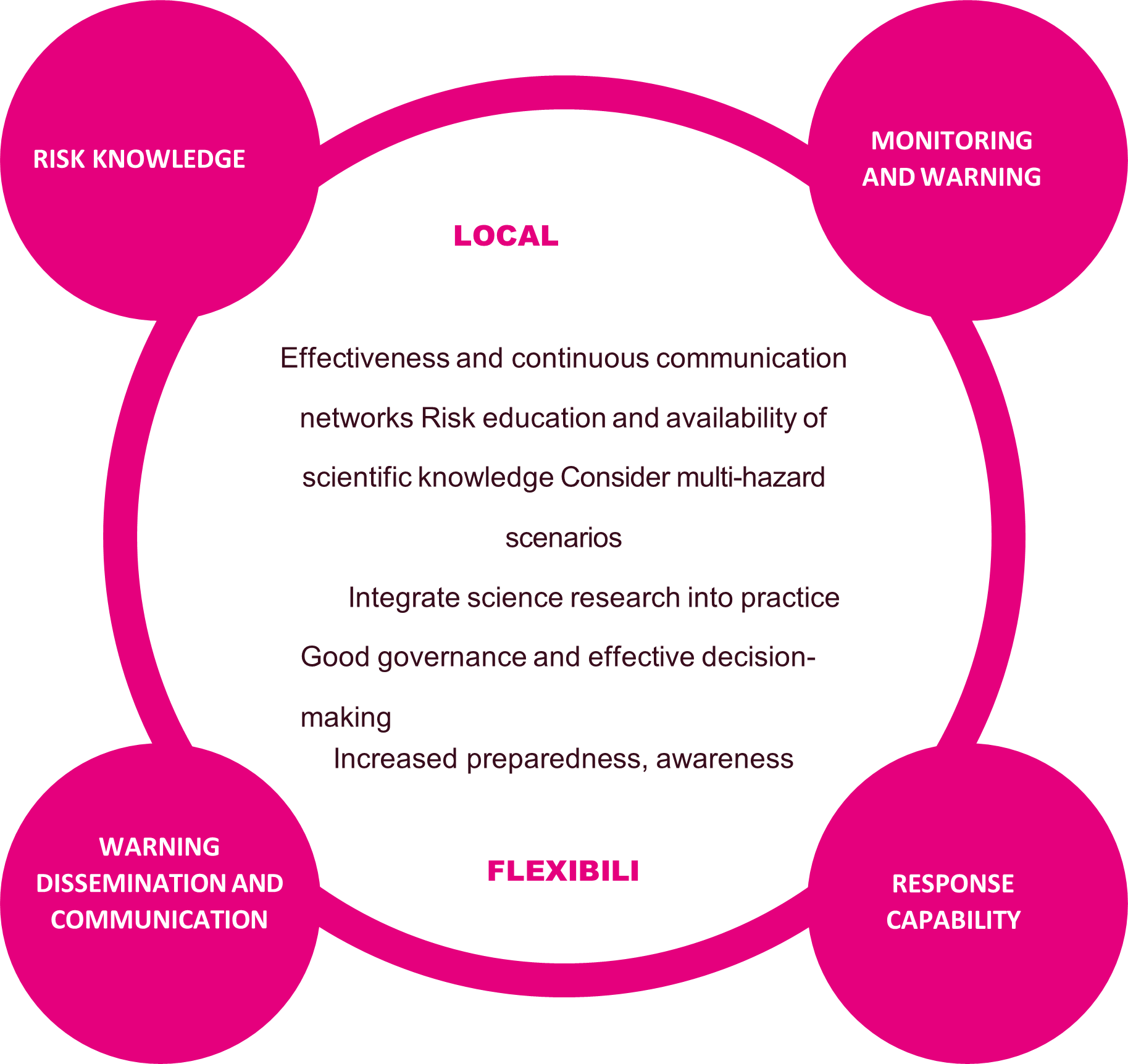

Warnings should translate knowledge into action through a multi-element, diverse, integrated, and engaging process rather than linear, one-directional, or top-down approaches. In many cases, processes linking individual components of warnings fail, rather than the individual components themselves typically related to vulnerabilities rather than hazards. Factors improving links among different elements are in Figure 3.

There is a need to stop viewing warnings as a system of independent sub-systems, but to explore further the interrelationships that occur between them, because they are multifaceted and cannot be modelled in a linear systematic function.

So-called near misses (such as when a warning was not issued but it was nearly needed) and false alarms (such as when a warning was issued but it was apparently not needed) should be defined for the warning system and described as part of the system’s performance metrics. It is not clear that either near misses or false alarms necessarily indicate failure. False alarms might sometimes make people less inclined to react to subsequent warnings, eroding trust and credibility – the ‘cry wolf’ syndrome. Yet, if local leadership has been involved from the beginning and if uncertainties are explained with a rationale for the false alarm, then credibility and engagement can be enhanced and people can be willing to accept more false alarms, especially in lieu of more near misses.

Multiple hazard early warning systems (MHEWS)

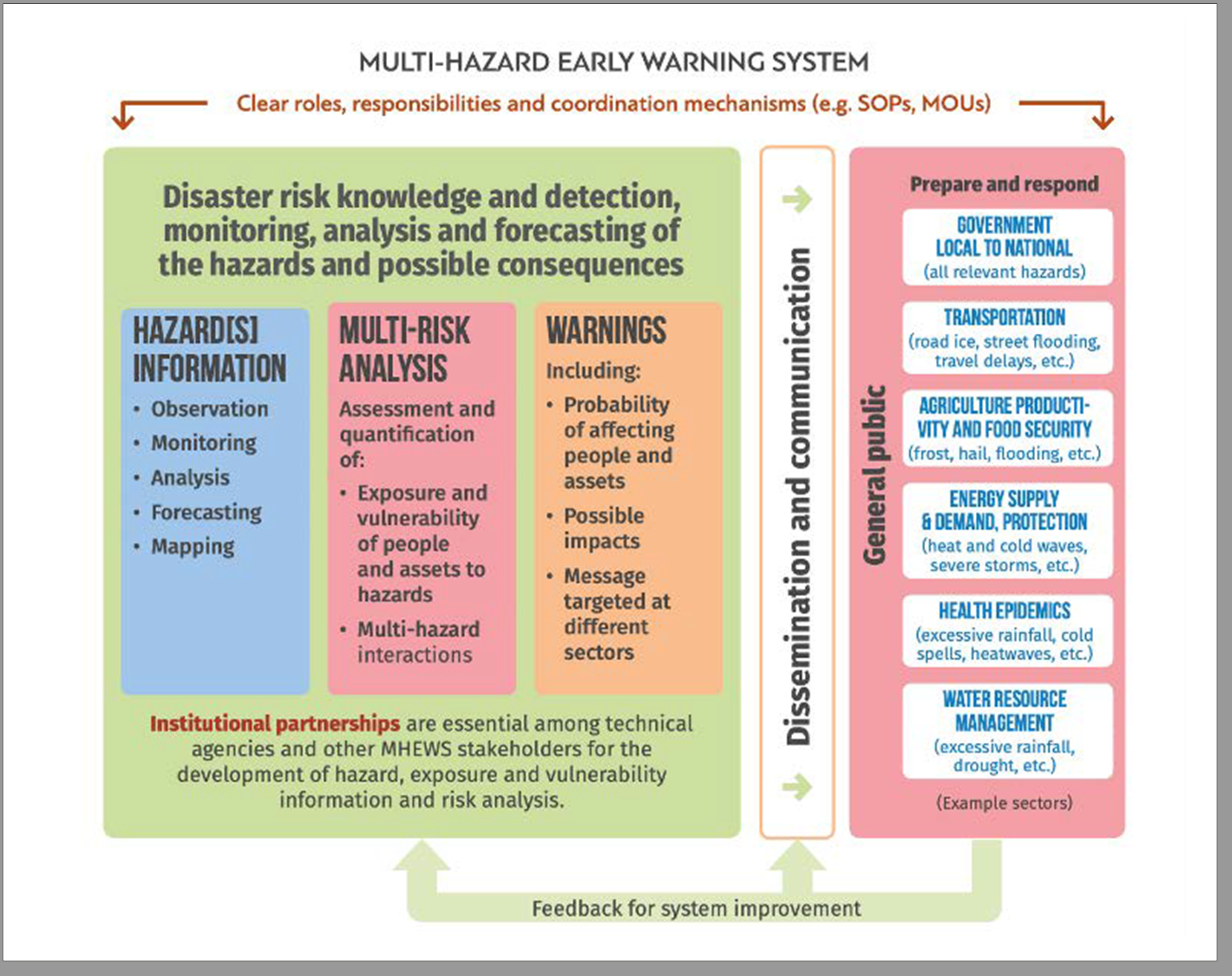

It is necessary to consider multiple hazard events and understand that warnings issued for different hazards may conflict. For example, flooding during the UK in 2020 required vulnerable populations to evacuate their homes and seek alternative shelter, whilst COVID-19 restrictions required those vulnerable populations to remain isolated. MHEWS attempt to bring in alignment the challenges of issuing multiple hazard warnings and preparing for the negative/contradicting, or positive/reinforcing actions that can emerge:

- MHEWS address several hazards and/or impacts of similar or different type in contexts where hazardous events may occur alone, simultaneously, cascading or cumulatively over time, and taking into account the potential interrelated effects.

- MHEWS have the ability to warn of one or more hazards which increases the efficiency and consistency of warnings through co-ordinated and compatible mechanisms and capacities

- For a MHEWS to operate effectively, national, regional, and local governments and vulnerable groups should create an integrated and comprehensive framework which clarifies the roles, responsibilities and relationships of all stakeholders within the system as exemplified in Figure 4.

Case Study on Developing Effective Warnings

COVID-19 in the UK

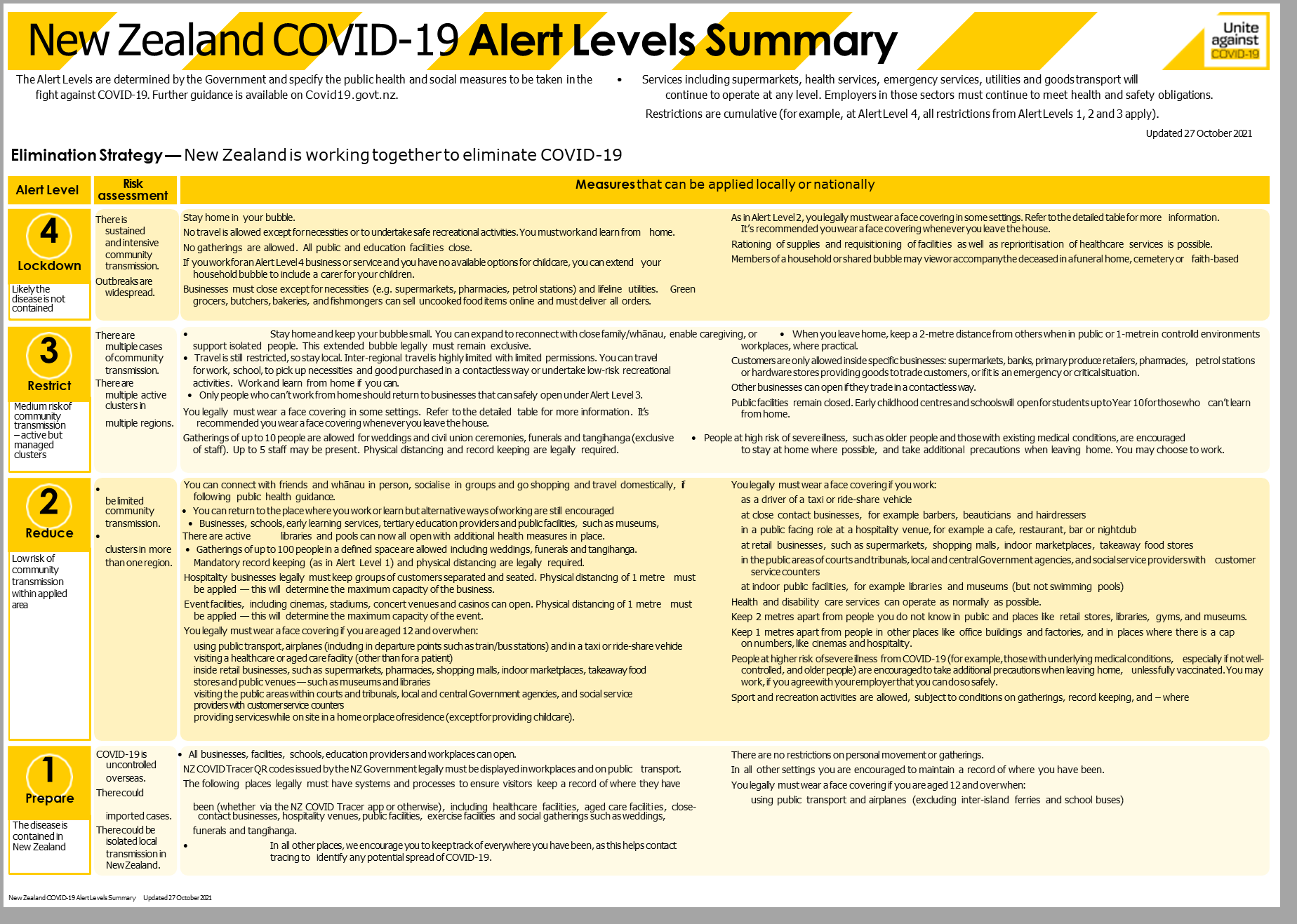

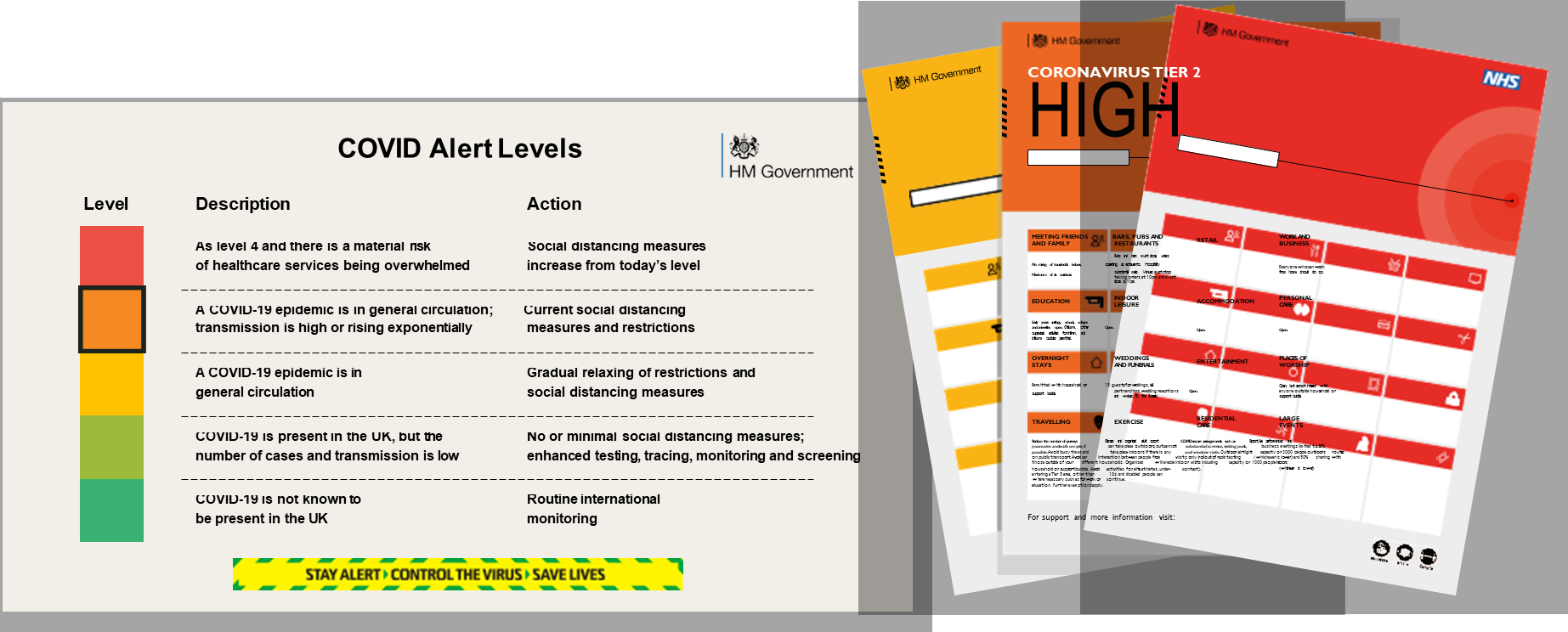

Alert levels were devised and implemented to manage the COVID-19 pandemic globally. In New Zealand, the alert level played a key role in the strategy to reduce lockdown measures by setting out four alert levels (Prepare, Reduce, Restrict and Lockdown) linked to the progress of the virus (see Figure 5). The levels provide clear guidance on the risk assessment and the range of measures in place for each alert level over a range of different sectors e.g. public health, personal movement, travel and transport, gatherings, public venues, workplaces and more. As a unified and comprehensive source of information, it gives authorities the credibility, accountability and transparency required so that everyone knows what to do and who is doing it, setting expectations and responsibilities from the beginning.

In contrast, the UK’s COVID-19 ALS was introduced nearly two months into the country’s first lockdown and faced numerous challenges of having to work with three other national alert systems across Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, difficulties involved in determining the parameter (the R-value) that drives the criteria for the alert level, and in establishing and co-ordinating the body that decides the alert level (the Joint Biosecurity Centre). Additionally, no clear guidance measures were associated with each alert level rendering the information irrelevant to the public. By adopting a security rubric, mirroring that used by the UK Terror Alert System, the UK’s COVID-19

ALS remained opaque. In October 2020, a further ALS was introduced to account for geographical variations via a local, three-tier alert system (medium, high and very high, see Figure 6). Whilst the system’s localisation provides clarity and guidance on actions, the system has been side-lined by national lockdowns.

These two case studies serve to demonstrate the value of transparency and clarity for ALS, the need for well-designed iconographies and the importance of communication to help the public lead themselves for informed actions and decisions.

Key lessons for planning, developing and implementing an ALS in the UK to translate into successful action include:

- Provide clear guidance that is transparent and freely available.

- Tie actions (social measures) to each alert level so the actions are required at each level are clear.

- Avoid a ‘terror’ security rubric to encourage the public to work together through This requires transparency and clarity (not feasible for a terror ALS context).

- Consider carefully the criterion used to determine thresholds, or whether it will be based on broader This requires multiple experts.

- The organisation deciding the alert level needs to establish strong multi-directional communication protocols across national and local governance.

- The alert level system cannot operate in It needs to be tied with other preventative and mitigative activities.

- If the alert system is to be used regionally effectively, more investment is needed for the public to be aware of the differences between regions.

- Alert levels should be issued to the public through a detailed briefings and made available on a government website and via media as a public-safety campaign.

- National level standardisation significantly reduces confusion whilst also being able facilitating local requirements.

- Enforcement of the rules are needed.

2. Engaging with stakeholders and the public to generate action

It is vital to engage with stakeholders and the public to generate actions from warnings. All too often, warnings are issued and they are not actioned and this is a result of poor integration with society, engagement by the public and stakeholders, and a lack of clearly defined roles and responsibilities. A range of tools and approaches have been used around the world to enhance public engagement and leadership for warnings. This can occur via two key approaches, from the top down, and from the bottom up.

Key policy top-down approaches to shape warnings and warning systems to consider according to specific local circumstances are:

- Public opinion surveys: These provide a large sample response to gather information and viewpoints.

- Focus groups: Small groups representing the public to provide free and open discussion about an issue.

- Citizen juries / panels: Public panels with independent questions to

- Responsible Research and Innovation: Works to listen to and account for public perspectives, also scrutinising the values and actions of science.

- Citizen science: Collect, process, and analyse data for people-powered and people- led research.

- Public activism: Campaigns and lobbying, such as to support people with HIV/ AIDS and end This includes Community Based and Driven Early Warning Systems.

- Grassroots campaigns: People leading themselves to influence wider policy and practice, this includes Community Based Early Warning Systems championed by NGOs and other civil agencies.

A UK mechanism which already exists is the Sciencewise programme, using public dialogues with scientists, organisations, policy makers and the public to ensure that UK policy is informed by the views and aspirations of the public. This same process could be applied for warnings on a regular basis. Whilst engagement is vital to help shape policy, it is also vital to help the ongoing practice, maintenance, and revisiting of warnings through simulations. Situations, personnel, hazards, and local and national contingences change over time and a warning system should be updated to reflect these changes. They are not static systems but adapting emergent ones.

B | Community Engagement

However, it is vital that bottom-up approaches are also encouraged and supported with the required resources. Ultimately, upstream engagement is highly recommended, where the first mile of warnings occurs:

‘The people who are affected by hazards, should be involved as the central component and should be involved from the beginning of the EWS design and operation.’

(Kelman and Glantz, 2014, p100)

Community-based Early Warning Systems empower communities to prepare for and confront hazards. This can be achieved via the involvement of community driven collection and analysis of information that enable warning messages to help a community to prepare actions to a warning and take actions to reduce the resulting loss or harm. These warning systems help create long-term warning systems that are part of the social process of a community and enable adaptation and resilience that exist outside of national or international capacities.

| COMMUNITY | ||

| Key elements | Based EWS | Driven EWS |

| Orientation | With the people | By the people |

| Character | Democratic | Empowering |

| Goals | Evocative, consultative | Based on needs, participatory |

| Outlook | Community as partners | Community as managers |

| Views | Community as organized | Community is empowered |

| Values | Development of peoples abilities | Trust in people’s capacities |

| Result/Impact | Initates social reform | Restructures social fabric |

| Key players | Social entrepreneurs, community workers and leaders | Everyone in the community |

| Methodology | Coordinated with technical support | Self-managed |

| Active early warning components (out of the four) | At least one is active (e.g., response capability) | All are active, especially the monitoring of indicators |

‘Overall, the main challenge is to focus on an early warning system as a social process, overcoming the entrenched view of early warning systems being mainly technical with those outside a community handing ‘expert’ information to those in a community.

Instead, perhaps ‘end-to-end-to-end’ is needed for an early warning system, indicating feedback loops and various pathways from which information comes and to which information flows.’

(Kelman and Glantz, 2014 pp105-106)

C | Integrating Education, Exchange, Engagement

It is important that bottom-up and top-down approaches are integrated to make sure they work in harmony, address any issues emerging from standardisation, and have communication processes in place (as per Figure 2). Therefore, public leadership and engagement are vital to develop effective warnings and related behaviour, meaning that local knowledge ought to feed into the processes operated by government. The United States Geological Survey’s Volcano Hazard Program (USGS VHP) serves as an excellent example of a government agency’s public successful outreach activities for warnings. Several tools are adopted to help create awareness, citizen scientists and effective responses to warnings over large populations (USGS VHP, 2021):

- Warning Assessments: Hazard assessment reports are the foundation for hazards education programmes and preparedness They outline the hazards, impact areas and maps of potential impacts, supporting emergency planners in developing preparedness and response plans. Increasingly, citizen science is being used to gather data, conduct experiments or develop low-cost approaches to help advance hazard knowledge and the warning process, fostering local leadership and action.

- Warning Preparedness: Personnel work directly with federal, state and local officials, as well as industry, media and the public, to increase awareness of location- specific hazards and to participate in response planning activities well ahead of crises. Multi-agency hazard response and co-ordination plans are developed for everyone involved in a particular region, facilitating warning They also provide guidance on making an emergency plan and compiling emergency kits for the public so that people can lead themselves for effective behaviour and action. Additional information is provided via hazard and risk maps, 3D modelling tools and fact sheets. The public are able to follow social media, subscribe to email alerts and contact key staff directly should they have any enquiries.

- Warning Support for Locals: Training events, presentations, workshops and partnerships necessary for grassroots preparedness and education are supported. Certified Crisis Awareness Courses have been developed to work across and link emergency Relationships are maintained via yearly reviews.

- Warning Information: Quick and accurate information with pre-established credibility is provided during a crisis via: (i) issuing authoritative forecasts, warnings and status updates of volcanic activity; (ii) investigating and rectifying reports of unrest and eruptions that are false or misleading; (iii) providing access to volcanic information and real-time data to the public via websites, social media and subscription services; and (iv) participating in targeted volcano-hazard education and planning activities.

- Warning Education: Opportunities are provided for educators to learn about volcanoes and volcanic hazards through summer teacher training, downloadable curriculum-related teacher resources, educational articles, and creative use of various USGS Additionally, observatories and offices have open-day events to engage with everyone and to support local leadership.

The success of the USGS VHP emerges from long-term development of trust and credibility with the public, supporting them for local leadership and providing resources in an open, transparent and accessible manner. Their activities help facilitate a well- established dialogue and relationship among the public, the scientists, and their agencies. When needed, warning communication then moves swiftly and is accepted.

Another example is Climate Outlook Forums, run around the world to bring together scientists and users for seasonal climate projections. Participants work together to develop probabilistic climate outlooks, determine sectoral implications, and train on using and communicating the outlooks. The key was to avoid users taking the probabilistic forecasts as fixed predictions, instead interpreting and trusting them as possible warnings for translating into on-the-ground, livelihood-related actions.

The 3 E’s of Education, Exchange, Engagement are vital to address Recommendation 2.

3. Overcoming silos to build trust and connections

Creating and supporting mechanisms to overcome silos and territorialism is vital. Encouraging idea and action exchange to build trust and connections that support action when a major situation arises is vital. It also provides a platform to learn from different agencies, disciplines, and hazards to devise better practices, tools, protocols, and integration. Four possible mechanisms for the UK to consider implementing include these recommendations:

A | A Warning Expert Committee Initiative

A Warning Expert Committee that sits across the UK Government providing leadership uniting all the agencies involved in warnings and facilitating engagement with external experts and local leaders to the government. Without removing individual agency responsibility for warnings, the Committee would bring together representatives from each agency / ministry with others from communities, academia, business, governments, and the non-profit sector to facilitate co-ordination, exchange and constructive critique. The committee would co-produce, combine and analyse knowledge and expertise from a wide range of people involved in warnings, supplementing the knowledge and expertise of the single agencies that have responsibility to warn.

There is potential for this committee to drive long-term awareness and credibility via:

- Working in the Cabinet Office Situation Room/Centre 24/7 to horizon scan for warnings.

- Feeding into the National Risk Register and updates of it, as well as related policies and legislation at all governance levels.

- Developing best practices and sharing lessons identified for action.

- Facilitating public leadership, education and awareness programmes and establishing more robust science communication according to contextualised local needs.

B | The Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE)

The UK Government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) provides scientific and technical advice to support government decision makers during emergencies. It is important that this body has within it a wide variety of expertise with a diversity of scientific approaches and is seen as genuinely independent and that is transparent in its workings.

C | Training and Exercise Programmes

Training and exercises help breaking down social barriers and build up awareness and connections so there is transfer from warning to action. It is vital to clarify responsibilities and roles and by simulating an event and clearing conflicts issues can emerge that can be easily addressed.

Scenarios can be developed, examined and tested such as Exercise Cygnus in October 2016 for a pandemic, and Exercise Triton 04 in June-July 2004 for coastal flooding in England and Wales. More such exercises should bring in people from organisations and with expertise beyond the specific hazard, such as pandemic or coastal flooding.

A vital component of scenarios includes imaginary futures that can help stakeholders and the public become aware of how a hazard may look, how it may affect them, and what their options are. Serious gaming tools can be utilised to help generate imaginary futures, using virtual futures and scenarios.

D | Integrating successful public engagement lessons

Building on Recommendation 3, several tools can be integrated to help create awareness, citizen scientists and effective responses to warnings over large populations, diverse organisations, and differing stakeholders:

- Warning Assessments;

- Warning Preparedness;

- Warning Support for Locals;

- Warning Information;

- Warning Education.

Summary

Examples throughout this report have highlighted that, whilst the UK has developed robust warnings, they frequently fail because people do not act or act ineffectively. The key characteristics of effective warnings need to be implemented alongside mechanisms for knowledge retention and exchange, particularly given that organisational staff often have a high turnover. Education is continual, especially regarding engagement between those with information and authority and the users. With complex, multi-hazard and/or cascading hazards and threats, warnings must engage directly with people affected, often looking to and supporting them for leadership.

‘Enhancing Warnings’ means a pair of triplet principals useful for defining warnings as a long-term social process:

3 I’s: Imagination, Initiative, Integration.

3 E’s: Education, Exchange, Engagement.

These six core principals help produce adaptable and effective warnings that match the key four characteristics (accuracy, flexibility, timeliness, and transparency), leading to effective action, saving UK lives and being an inspiration to the world.

References

Day, S. & Fearnley (2015) A classification of mitigation strategies for natural hazards: implications for the understanding of interactions between mitigation strategies.

Natural Hazards – online first (doi: 10.1007/s11069-015-1899-z).

Fearnley, C. J. (2013) Assigning a volcano alert level: negotiating uncertainty, risk, and complexity in decision-making processes. Environment and Planning a, 45(8), 1891-1911.

Fearnley, C. J., & Beaven, S. (2018) Volcano alert level systems:

managing the challenges of effective volcanic crisis communication. Bulletin of Volcanology, 80(5), 1-18.

Fearnley, C., Wilkinson, E., Tillyard, C.J., Edwards, S.J. (2016)

Natural Hazards and Disaster Risk Reduction Putting Research Into Practice. Routledge.

Fearnley, C. J., McGuire, W. J., Davies, G., & Twigg, J. (2012) Standardisation of the USGS Volcano Alert Level System (VALS): analysis and ramifications. Bulletin of volcanology, 74(9), 2023-2036.

Garcia C, Fearnley CJ (2012) Evaluating critical links in early warning systems for natural hazards.

Environmental Hazards 11(2):123-137 (doi:10.1080/17477891.2011.609877).

Geleta, B. (2013) Community early warning systems: guiding principles. Technical report, Red Cross.

Glantz, M. H. (2007) Heads Up! Early Warning Systems for Climate, Water and Weather.

Global survey of early warning systems (2006).

Golnaraghi, M. (Ed.). (2012) Institutional partnerships in multi-hazard early warning systems: a compilation of seven national good practices and guiding principles. Springer Science & Business Media.

Kelman, I. (2006) Warning for the 26 December 2004 tsunamis. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal. (doi: 10.1108/09653560610654329).

Kelman, I., Ahmed, B., Esraz-Ul-Zannat, M., Saroar, M. M., Fordham, M., & Shamsudduha, M. (2018) Warning systems as social processes for Bangladesh cyclones. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal. (doi: 10.1108/DPM-12-2017-0318).

Kelman, I., & Glantz, M. H. (2014) Early warning systems defined. In Reducing disaster: Early warning systems for climate change (pp. 89-108). Springer, Dordrecht.(doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-8598-3_5).

Maskrey, A. (1997) Report on national and local capabilities for early warning.

International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction (IDNDR).

Mileti, D. (1999) Disasters by design: A reassessment of natural hazards in the United States.

Joseph Henry Press.

New Zealand Government (2021) COVID-19 Protection Framework.

United Kingdom Government (2021) UK COVID-19 alert level methodology: an overview.

United States Geological Survey Volcano Hazard Programme (2021) Volcano Hazards.

World Metorological Organization (2018) Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems: A Checklist. 1-20.

Wynne, B. (1992) Misunderstood misunderstanding: social identities and public uptake of science.

Public understanding of science, 1(3), 281.

Wynne, B., Lash, S., Szerszynski, B., & Wynne, B. (1996) May the sheep safely graze?

Risk, Environment and Modernity: Towards a New Ecology (p44).

Zschau, J., & Küppers, A. N. (Eds.). (2013) Early warning systems for natural disaster reduction.

Springer Science & Business Media.